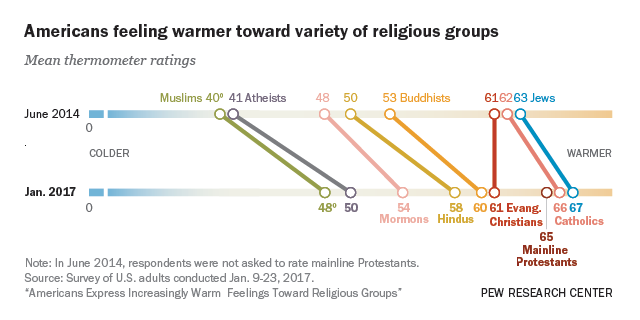

Americans hold warmer feelings towards various religious groups than they did just a few years ago, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Atheists and Muslims still registered less favorable responses as measured by a “feelings thermometer” ranging from zero to 100. But warmth of Americans’ feelings toward these two groups has increased from 40 for Muslims and 41 for atheists to 48 and 50, respectively. Jews and Catholics remain among the groups receiving the warmest ratings—even warmer than the last such survey in 2014. Mormons and Hindus have shifted from more neutral places on the thermometer to relatively warmer scores of 54 and 58, respectively. Buddhists have moved up from 53 to 60. Evangelicals were the only group to stay the same, remaining at 61 on the scale.

(Pew Forum, http://www.pewforum.org)

An analysis of 40 countries looking at the relation between religiosity and “economic communitarianism,” or compassionate concern for the well-being of others, finds that religious involvement and an orthodox orientation positively affect extending compassion to those less fortunate, according to a study by Tom VanHeuvelen and Robert V. Robinson. Writing in the journal Social Currents (online March), the authors analyze the European Values Survey from 2008–2009 focusing on the three dimensions of religiosity: belief, behavior, and belonging (such as congregational involvement). Contrary to the popular notion that orthodox religion fosters an exclusive attitude toward whom adherents regard as a “brother,” the analysis finds that frequent attendees at services and “high-attending religious orthodox people” are more universalistic in extending compassion equally across social categories than those who attend infrequently or low attending “modernists.”

The authors tested the criticism that orthodox concern for others would mainly consist of care for those within their own faith tradition and found that compassionate concern “for a wide range of social categories are remarkably robust.” While previous studies have found Protestants to be individualistic, the authors find that this tradition is not any less communalistic than others, though they were less universalistic than Muslims and Jews. The communitarian concern of Muslims, especially for the well being of immigrants, suggests that their immigration to Europe could “benefit left parties focused on economic protection.”

(Social Currents, http://journals.sagepub.com/toc/scu/current)

British young people tend to disagree that their country has a specific religious identity, though they think religion does play an important part in people’s lives, according to a survey of the newly launched Faith Research Centre. The survey found that adults aged 18–24 were the least likely to describe Britain as a Christian country (31 percent) and the most likely to describe Britain as a country with no specific religious identity (41 percent). Older adults were significantly more likely to view Britain as a Christian country (74 percent). But the percentages were higher for young people believing that religion is important in tackling terrorism and in understanding the world (at about 50 percent).

(Faith Research Centre is being launched by the consultancy firm ComRes: http://www.comresglobal.com)

A study of friendship networks among young people in Germany finds a divide between Muslims and other students, with each group preferring one another’s company more, according to a study in the European Sociological Review (February). Lars Lezsezensky and Sebastian Pink look at school-based friendship network panel data, specifically at friendship choices of Christian, Muslim, and non-religious students in Germany. They find the tendency to have friends of the same religion among both Christians and Muslims, but the former tended to befriend non-religious youth as often as their Christian peers, and vice versa. Christian and non-religious youth were hesitant to befriend Muslim peers, suggesting that the same negative feelings about the rapid growth of the Muslim population as found among European adults may already be in place during the teen years. Against expectations, the youth in the study were no more hesitant to befriend highly religious teens in either group than more moderate ones. In fact, Muslim students even preferred highly religious over less religious Christian peers, suggesting that religion’s importance may override religious difference and create new bonds.

(European Sociological Review, https://academic.oup.com/esr/issue/33/1)

After reaching a peak in 2010, the annual number of people leaving the Roman Catholic and the Reformed Churches in Switzerland diminished in 2011, but then started to increase again, with a more marked increase in 2015, the most recent year for which data is available, writes Judith Albisser in a three-part report released by the Swiss Institute for Pastoral Sociology (January 26, Feb. 8, and Feb. 20). In 2013, 8 out of 1,000 members per year left one of the historical Churches. In 2015, 10 out of 1,000 did so. While there are regional variations, the trend can be observed in nearly all areas of Switzerland. The decline in members is especially strong for the Reformed Church, both in percentage and absolute numbers. The Reformed made up more than 56 percent of the Swiss population in 1950. In 2015, their share was down to less than 25 percent. In Geneva, long seen as a world center for the Reformed faith, Reformed believers now make up only 10 percent of the population. While the share of the Catholic Church declined percentage-wise as well (37.3 percent of Swiss population in 2015), it managed to remain stable in absolute numbers due to its larger share among migrants. Regarding migrants to Switzerland, 53 percent belong a Christian denomination, while 28.6 percent have no affiliation and 13.4 percent are Muslims.

(Schweizerisches Pastoralsoziologisches Institut (SPI), https://spi-sg.ch)

A survey of Syrian refugees provides a revealing if not necessarily representative snapshot of their political and religious beliefs and attitudes, suggesting that the differences between those loyal to the government and those supporting the rebels are not very significant. The unsettled and temporary situation of Syrian refugees, with only about two-thirds of them registered, makes a representative sample of this population difficult, but a survey of 2,000 respondents conducted by households in a refugee camp in Lebanon finds that there was not a strong political component to their faith. In the Hoover Digest (Winter), Daniel Corstange writes that a little over half of the respondents to the poll he conducted in cooperation with the Beirut-based Information International supported the Syrian opposition and about 40 percent supported the government, though the Arab majority did not uniformly line up with the latter.

The view that those supporting the rebels were fervently religious, supporting Islamic politics, while government supporters were largely secular did not hold up. The refugees as a whole expressed a good deal of Islamic devotion, with more than three-quarters saying they pray daily and read the Quran weekly, and opposition supporters did see a greater role for politics in Islam. But within the opposition, nationalist supporters were no more secular than their Islamist counterparts. Only about a third of all the respondents said that religion is even somewhat important in either economic or political affairs.

(Hoover Digest, http://www.hoover.org/publications/hoover-digest)