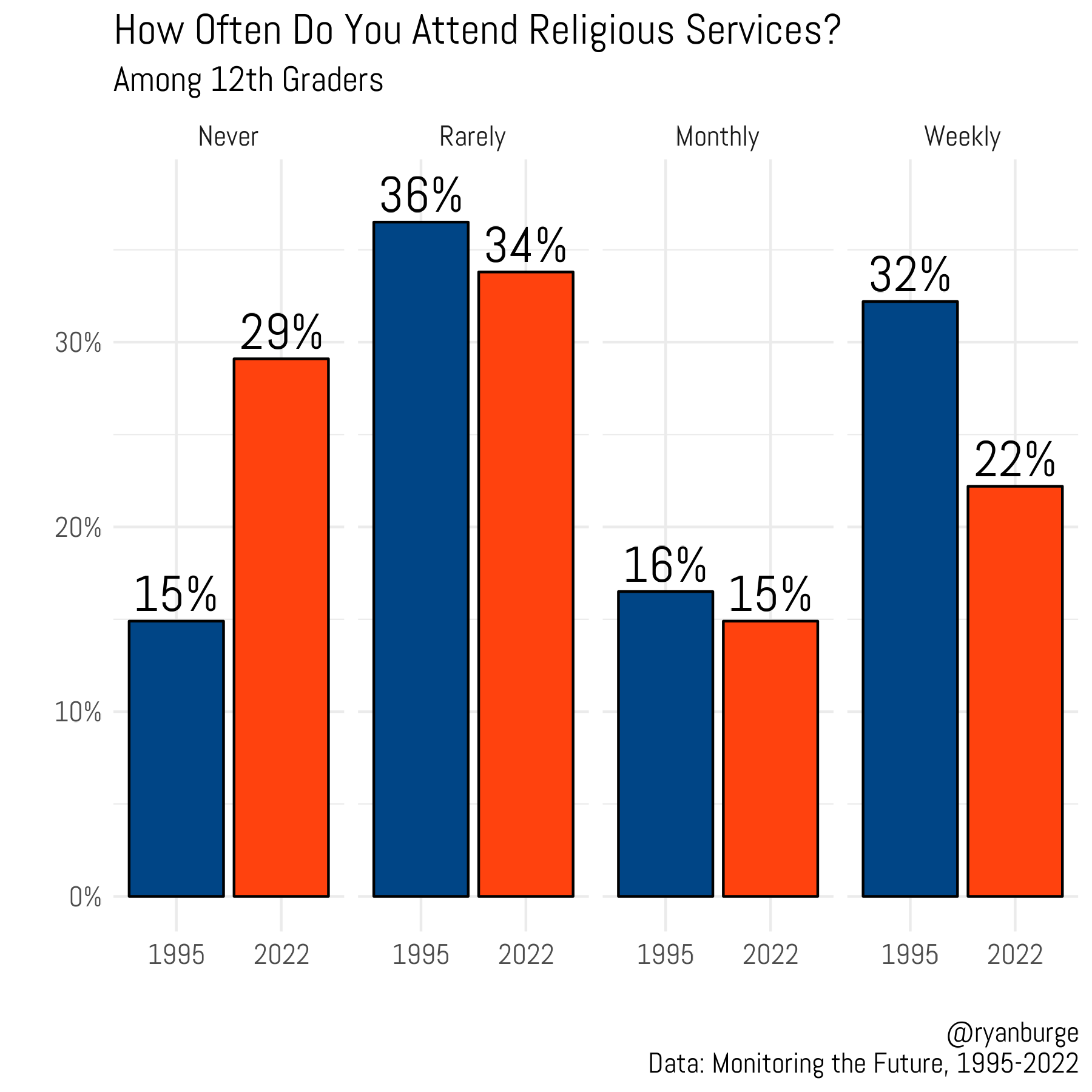

On the perceived importance of religion, the results are similar to the responses about religious attendance, with much of the shifting taking place on the ends. Among high school seniors in 1995, 30 percent said that religion was very important to them, a share that dropped to just 20 percent by 2022. At the same time, the share that said that religion was not important at all almost doubled, going from 15 percent to 28 percent. Burge finds that in 1995, a high school senior was twice as likely to say that religion was very important as they were to say it was not important at all. By 2022, a 12th grader was almost 50 percent more likely to place no importance on religion than to say it was very important. But, again, the middle two categories have stayed very static during this time period. In 1995, the most chosen responses of high school seniors were attending church weekly and indicating that religion was very important, with about one in five respondents fitting into these categories. Just 9 percent of the sample said that they never attended religious services and that religion was not important at all. Now, only 11 percent of high school seniors attend services weekly and deem religion very important. Burge concludes, “There’s no other way to look at this than high school seniors, male, female, educated, non-educated, are a whole lot less religious now than they were back in the mid-1990s.”

Many Christians also said that their religious beliefs made them feel like a minority group (38 percent of Hispanic Protestants, 37 percent of white evangelicals, and 25 percent each of Catholics and black Protestants). Other findings include an increase in the share of respondents who say that the best course of action is to avoid talking about religion if someone disagrees with you (from 33 percent in 2019 to 41 percent today) and an increase (to 48 percent from 42 percent four years ago) in the share who agree that there is “a great deal” or “some” conflict between their religious beliefs and mainstream American culture. Seventy-two percent of religiously unaffiliated adults accuse conservative Christians of having gone too far in pushing religion in government and public schools, while about the same percentage (73 percent) of conservative Christians say the same about secular progressives pushing secularism.

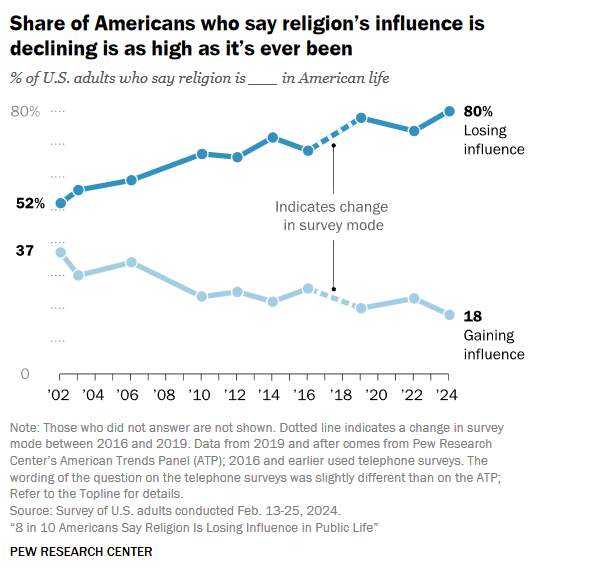

(The Pew report can be downloaded from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2024/03/15/8-in-10-americans-say-religion-is-losing-influence-in-public-life/)

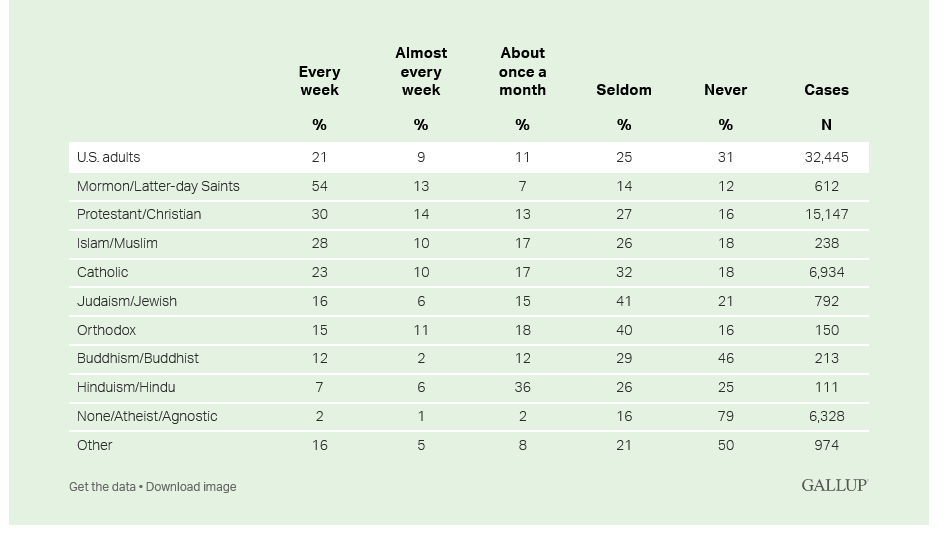

(The Gallup report can be downloaded at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/642548/church-attendance-declined-religious-groups.aspx)

An ultra-Orthodox Jewish man receives a vaccination against the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) at a temporary vaccination centre in the Jewish settlement of Beitar Illit, in the Israeli-occupied West Bank February 16, 2021.Source: Reuters | Ronen Zvulun.

Other surveys confirm a higher rate of refusal among younger ultra-Orthodox women in comparison with older women, while no age difference has been observed among male ultra-Orthodox. While this requires further study, the authors suggest that “the risk of harming fertility may be perceived by ultra-Orthodox women as a potential violation of a major religious role and the core role of women in this community.” Compared with other subgroups, the Lithuanian/Misnagdim had a higher rate of vaccination and lower mistrust of its efficacy, reflecting their greater openness toward secular information and scientific data. Among those who refused to get vaccinated, with multiple responses possible, the most frequent answer was that they had received immunity from Covid-19 (63 percent), while 36 percent cited concerns about the harm the vaccine might cause in the long run. Very few selected religious reasons for not being vaccinated, with 5.3 percent stating that their rabbi had told them not to get vaccinated. Except for the possible connection between religious beliefs and concerns about harm to fertility among women, “barriers to vaccination among the ultra-Orthodox Jews are not religious-framed but more related to lack of knowledge, fears, trust, and logistics.”

(Journal of Religion and Health, https://link.springer.com/journal/10943)