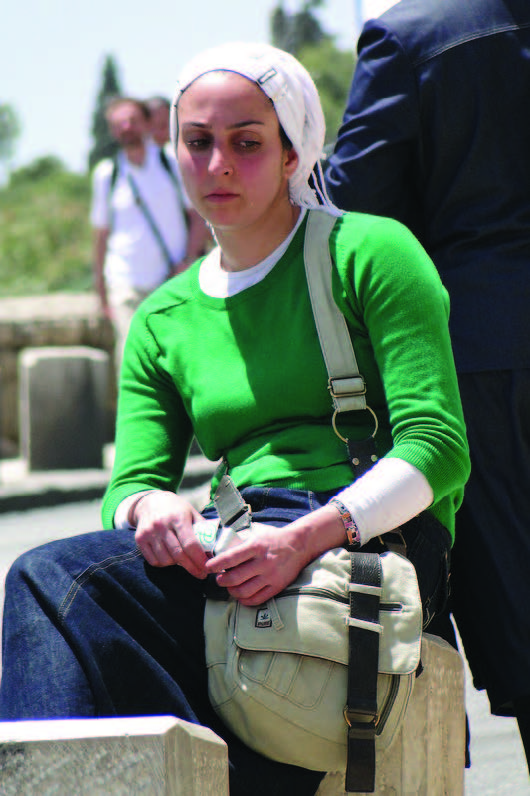

Source: Adam Jones, 2011 | Flickr.

The view of ultra-Orthodox Judaism as a conservative force in Israeli society is only half the picture and does not account for the changes taking place among ultra-Orthodox women on reproductive and work decisions, writes Michal Raucher of Rutgers University in the online magazine The Conversation (May 17). Reflecting on interviews she conducted between 2009 and 2011 with ultra-Orthodox women about their reproductive experiences, Raucher sees many of their liberalizing attitudes reflected in the dynamics in ultra-Orthodox communities in Israel today. Although known only for having many children, Raucher found that after several pregnancies ultra-Orthodox women begin to make their own reproductive decisions, often in contradiction to rabbinic expectations. Knowing that rabbis expect ultra-Orthodox members to consult their rabbis on medical care, doctors might ask a woman who requests some form of birth control about their rabbi’s approval.

According to Raucher, this relationship encourages mistrust among these women as they distance themselves from both doctors and rabbis when it comes to reproductive care. At the same time, this rejection of external authority over pregnancy and birth is supported by the ultra-Orthodox belief that pregnancy is a time when women embody divine authority. “Women’s reproductive authority, then, is not completely countercultural; it’s embedded in ultra-Orthodox theology,” Raucher writes.

While gender segregation has long been another feature of ultra-Orthodox traditions, men and women now lead very different lives. In Israel, ultra-Orthodox men spend most of their days in a religious institute studying sacred Jewish texts, for which they earn a modest government stipend. While the community still valorizes poverty, ultra-Orthodox women have become the primary breadwinners and have increasingly attended college in order to support their large families. They are now entering the workforce at a similar rate to their secular counterparts and are forging new career paths in technology, music and politics. This can be seen in recent TV shows depicting a more nuanced understanding of gender and authority among ultra-Orthodox Jews, such as the popular Netflix series Shtisel.

A proliferation of new formal and informal leaders in ultra-Orthodox society, such as the rise of assistants or informal helpers to rabbis, called askanim, has also led to a diffusion of authority. Understanding ultra-Orthodox women’s experiences would have helped explain why they have turned to theories that are repackaged in ultra-Orthodox language, like anti-vaccination campaigns. These women would also have revealed that poverty and cramped living spaces make social distancing almost impossible. Raucher argues that, rather than focusing exclusively on prominent rabbis who have rejected public health measures, “attention to women’s complicated experiences with the medical establishment would have highlighted the mistrust and doubt that permeates the ultra-Orthodox community’s relationship to public health measures.”

(The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/ultra-orthodox-jewish-women-are-bucking-thepatriarchal-authoritarian-stereotype-of-their-community-160148)