Not only have recent Salafist political projects failed to materialize, but Salafis themselves are gaining less of a hearing and less influence among Muslims in a wide range of Islamic countries and contexts, write Muhammad Sani Umar and Mark Woodward in the journal Contemporary Islam (online August). While the campaigns of jihadic Salafist coalitions in Iraq, Syria, Nigeria, and Mali have met resistance if not mass flight, the authors note that the “limited success of the larger Salafi religious, cultural and social agendas has not yet received the attention it deserves.” Salafi Muslim organizations have spent millions seeking to peacefully promote their strict form of Islam around the world through the building of mosques and through scholarship programs for study in Saudi Arabia. Umar and Woodward look specifically at Indonesia and Nigeria, two of the world’s most populous Muslim countries in which Salafi Islam has invested but found limited appeal. Despite vocal Salafists’ apparent dominance of public discourse in these countries, Umar and Woodward, in their ethnographic investigation of how people resist this movement, find what they call an “Izala effect”—a reaffirmation of local culture in response to Salafist promotion, “Izala” being an abbreviated name for the Nigerian Salafist group from which the violent Boko Haram organization emerged. The “Izala effect” signifies that the growth of Salafism has had the unintended consequence of reaffirming the local beliefs and practices it has been determined to eradicate, including a reassertion of “the Quranic bases of Sufism [mystical Islam], and…intensification of Muslim cultural practices that are deeply influenced by Sufi spiritual teachings.”

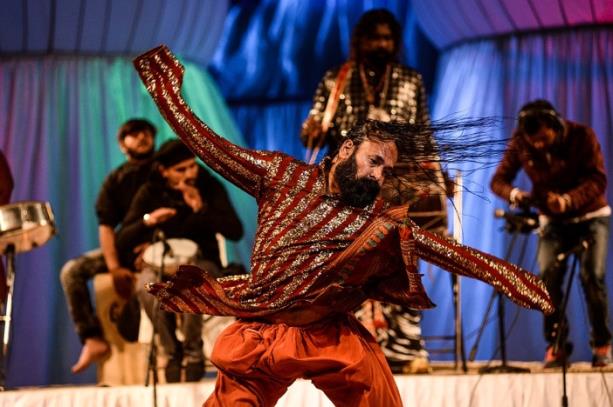

Nowhere is the Izala effect seen more clearly than in the failure of Salafists to stem the tide of religious songs and popular cultural practices that form important parts of Muslim identity, especially in Southeast Asia. The failure of the Salafist critique against Sufism can be seen in the growth of Sufist orders and the way that ever more flamboyant and exaggerated expressions of that movement have become increasingly widespread, according to Umar and Woodward. “Many rituals have been ramped up from home- or mosque-based events that attract tens of devotees to massive public spectacles attracting hundreds of thousands. The Salafi interdiction of songs and music is drowned in the tidal waves of thousands and thousands of fans who attend musical performances by virtuoso Sufi artistes.” Umar and Woodward cite surveys of Southeast Asia and West Africa showing a low number of Muslims identifying with Salafi groups, which, they add, is also the case in diaspora communities in the UK and Sweden. Whereas in the past Sufi groups have ignored or resisted Salafi condemnations of their beliefs and practices, or “domesticated” them by mixing them with their own doctrines, the authors write that most recently they have gone on the offense, “impugning their Islamic piety, accusing them of greed [and] sexual depravity, belittling their pretensions to Islamic learning, and praying to God to consign them to hellfire.” This aggressive backlash has the potential to radicalize Sufism in a similar way to Salafism, which can already be seen in violent episodes in Nigeria where Sufis and Salafis have clashed over the control of mosques.

(Contemporary Islam, https://link.springer.com/journal/11562)