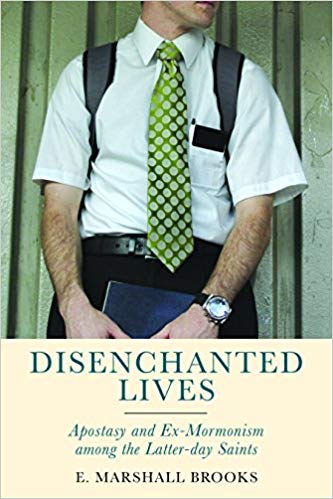

As the number of LDS members leaving the church is said to be growing, Disenchanted Lives (Rutgers University Press, $34.95) by E. Marshall Brooks investigates the distinctive subculture that has developed among Mormon apostates. Brooks conducts ethnographic research among ex-Mormon support groups, online forums, and informal gatherings in Utah. The book does not see Mormon apostasy as stemming from members who already have “one foot outside of the door of the faith,” but rather as the result of internal tensions and contradictions in the church that affect dedicated members who had few intentions of departing from the faith (one chapter looks at the “sudden” nature of many cases of Mormon apostasy). Brooks notes that his sample of ex-Mormons do not necessarily reflect most people who have left the LDS church, and there is little indication that the much-publicized departures and public protests of church liberals, feminists, and gay rights activists are widespread. But Brooks still tends to stress that cases of Mormon disaffection represent a “crisis of apostasy.” This fits with his treatment of these ex-members as experiencing trauma, bigotry, stigma and “social suffering” at the hands of a church that has repressed its history and a religious culture too dismissive of doubt and dissent. The ex-members’ anger, depression, and atheism are viewed by Brooks as constituting a “reasonable response” to a dysfunctional and harmful religion.

The sympathetic treatment of ex-members extends to how Brooks finds that they experience apostasy not just as a rational dismissal of church doctrine but also as a bodily effect of lifelong observance (in a similar way to recent studies of ex-Hasidic Jews). There have been other studies of apostasy in new religious movements that are less exclusively focused on ex-members’ portrayal of their former group in mostly negative terms and that attempt to balance their treatment of the group with accounts by current members and historical experiences. Brooks does include a short section distinguishing “angry ex-Mormons” from “middle-way Mormons” who still identify with the Mormon people even if not with LDS beliefs, but he does so to show how the former group uses anger to patrol boundaries between themselves and the church and to “insulate themselves from its pernicious influence.