![]() The April issue of the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute features an interesting interchange between psychology, anthropology, and religion relating to how people experience the relationship between their minds and gods and spirits,

The April issue of the Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute features an interesting interchange between psychology, anthropology, and religion relating to how people experience the relationship between their minds and gods and spirits,  using charismatic and Pentecostal congregations as its case studies. The special issue reports on the findings of the Mind and Spirit project, a Templeton-funded initiative based at Stanford University and headed by anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann, which brings together an interdisciplinary team to study spiritual experiences in Pentecostal and charismatic churches in the U.S., China, Ghana, Thailand, and Vanatu/Oceania. Although these churches have obvious similarities, they belong to societies that have different conceptions of mind that bear on their conceptions of God and spiritual experience. One finding is that the “more a person imagines the mind-world boundary as porous (permeable), the more they report a vivid, near-sensory experience of invisible others.” For instance, the American Pentecostals rarely reported—or were hesitant to report—that they heard the voice of God, while there was more of a tendency to do so in Ghana. Luhrmann adds that the project hopes to show that “different ways of representing human-world relationships shape something so basic as sensory evidence.” For more information on this issue, visit: https://rai.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14679655

using charismatic and Pentecostal congregations as its case studies. The special issue reports on the findings of the Mind and Spirit project, a Templeton-funded initiative based at Stanford University and headed by anthropologist T.M. Luhrmann, which brings together an interdisciplinary team to study spiritual experiences in Pentecostal and charismatic churches in the U.S., China, Ghana, Thailand, and Vanatu/Oceania. Although these churches have obvious similarities, they belong to societies that have different conceptions of mind that bear on their conceptions of God and spiritual experience. One finding is that the “more a person imagines the mind-world boundary as porous (permeable), the more they report a vivid, near-sensory experience of invisible others.” For instance, the American Pentecostals rarely reported—or were hesitant to report—that they heard the voice of God, while there was more of a tendency to do so in Ghana. Luhrmann adds that the project hopes to show that “different ways of representing human-world relationships shape something so basic as sensory evidence.” For more information on this issue, visit: https://rai.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14679655

![]() It is unusual when a secular social science journal devotes a special issue to a sociologist of religion, but David Martin, who died last year, was an unusual sociologist who specialized in religion. The journal Society (April, 2020) convened a symposium, asking several contributors from different disciplines about the achievement and relevance of Martin’s work and the result is a fascinating collection of articles that extend his work in such areas as Pentecostalism in Latin America, secularization, British religion, the religious elements in art, music, and poetry, and the relation between theology and sociology. Anglican theologian Martyn Percy expands on

It is unusual when a secular social science journal devotes a special issue to a sociologist of religion, but David Martin, who died last year, was an unusual sociologist who specialized in religion. The journal Society (April, 2020) convened a symposium, asking several contributors from different disciplines about the achievement and relevance of Martin’s work and the result is a fascinating collection of articles that extend his work in such areas as Pentecostalism in Latin America, secularization, British religion, the religious elements in art, music, and poetry, and the relation between theology and sociology. Anglican theologian Martyn Percy expands on  Martin’s treatment of secularization by looking at how and why cathedrals in the Church of England show a steady growth in attendance even while parishes are showing a sharp drop in members.

Martin’s treatment of secularization by looking at how and why cathedrals in the Church of England show a steady growth in attendance even while parishes are showing a sharp drop in members.

Percy argues that cathedrals don’t show the “high threshold-high rewards” dynamic of strict churches; in fact, he adds that the inclusive and low threshold (or cost) of cathedral attendance, stressing contemplation and solitude rather than activity and community, can serve to “sacralize civic life.” In another article, Martin’s long-time colleague Grace Davie updates his pioneering study of Pentecostalism in Latin America and the revival of religion in Eastern Europe, noting that the growth of populism in the latter region is a new dynamic that has to be accounted for. Bernice Martin explores her late husband’s last project on resilient Christian elements in the arts and literature, noting how he remained a critic to the end of the idea that secularization means an inevitable loss of religious vitality in all aspects of society. For more information on this issue, visit: https://www.springer.com/journal/12115

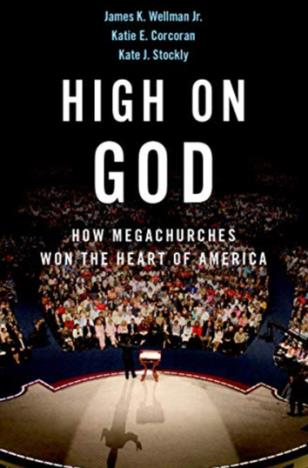

![]() The new book High on God (Oxford University Press, $24.95), by James K. Wellman Jr., Katie E. Corcoran, and Kate J. Stockly, blends sociological theory on the emotions with in-depth research on 12 contemporary megachurches. The interviewees expressed the widespread feeling among interviewees that they and experienced a spiritual “high” in their participation in megachurches. These emotions are linked to the charisma of the pastor but also stem from the contagious nature of the commitment and enthusiasm that members pass on to each other during worship and in such activities as small groups and service programs. Most the book presents a fairly positive picture of megachurches, with the authors viewing them as centers of community life and emotional and social support (especially in relation to families). The charge that megachurches are sources of religious right activism is not borne out in the authors’ research. The “parochial cosmopolitan” culture of most megachurches tend to focus on the “core issues of salvation; growing each person’s character; building communities of healthy, happy marriages and families,” and outreach to the community. While members may join Christian right organizations or vote for Donald Trump, the churches themselves don’t address contentious political issues in their public life. Even the prosperity teachings of some of these churches do not always signal clergy fraud and members’ gullibility as the authors find that people take what they need from such teachings and balance it with common sense.

The new book High on God (Oxford University Press, $24.95), by James K. Wellman Jr., Katie E. Corcoran, and Kate J. Stockly, blends sociological theory on the emotions with in-depth research on 12 contemporary megachurches. The interviewees expressed the widespread feeling among interviewees that they and experienced a spiritual “high” in their participation in megachurches. These emotions are linked to the charisma of the pastor but also stem from the contagious nature of the commitment and enthusiasm that members pass on to each other during worship and in such activities as small groups and service programs. Most the book presents a fairly positive picture of megachurches, with the authors viewing them as centers of community life and emotional and social support (especially in relation to families). The charge that megachurches are sources of religious right activism is not borne out in the authors’ research. The “parochial cosmopolitan” culture of most megachurches tend to focus on the “core issues of salvation; growing each person’s character; building communities of healthy, happy marriages and families,” and outreach to the community. While members may join Christian right organizations or vote for Donald Trump, the churches themselves don’t address contentious political issues in their public life. Even the prosperity teachings of some of these churches do not always signal clergy fraud and members’ gullibility as the authors find that people take what they need from such teachings and balance it with common sense.

But in the final chapters of the book, Wellman, Corcoran, and Stockly make the case for the “dark side” of megachurches. In fact, it is the charismatic nature of megachurch leadership that enables both pro-social and negative behavior in these congregations. Using statistics and case studies of 56 megachurches that have experienced leadership scandals, usually involving financial mismanagement, and abuse of a spiritual, emotional, or sexual nature (most recently at the flagship Willow Creek Church), the authors argue that it is especially the “soft patriarchalism” of these congregations that enable their male leaders to wield their power and charismatic appeal on female members. These scandals unleash the obverse of the positive spiritual energy that megachurches typically generate, leading to discord and cynicism among members.