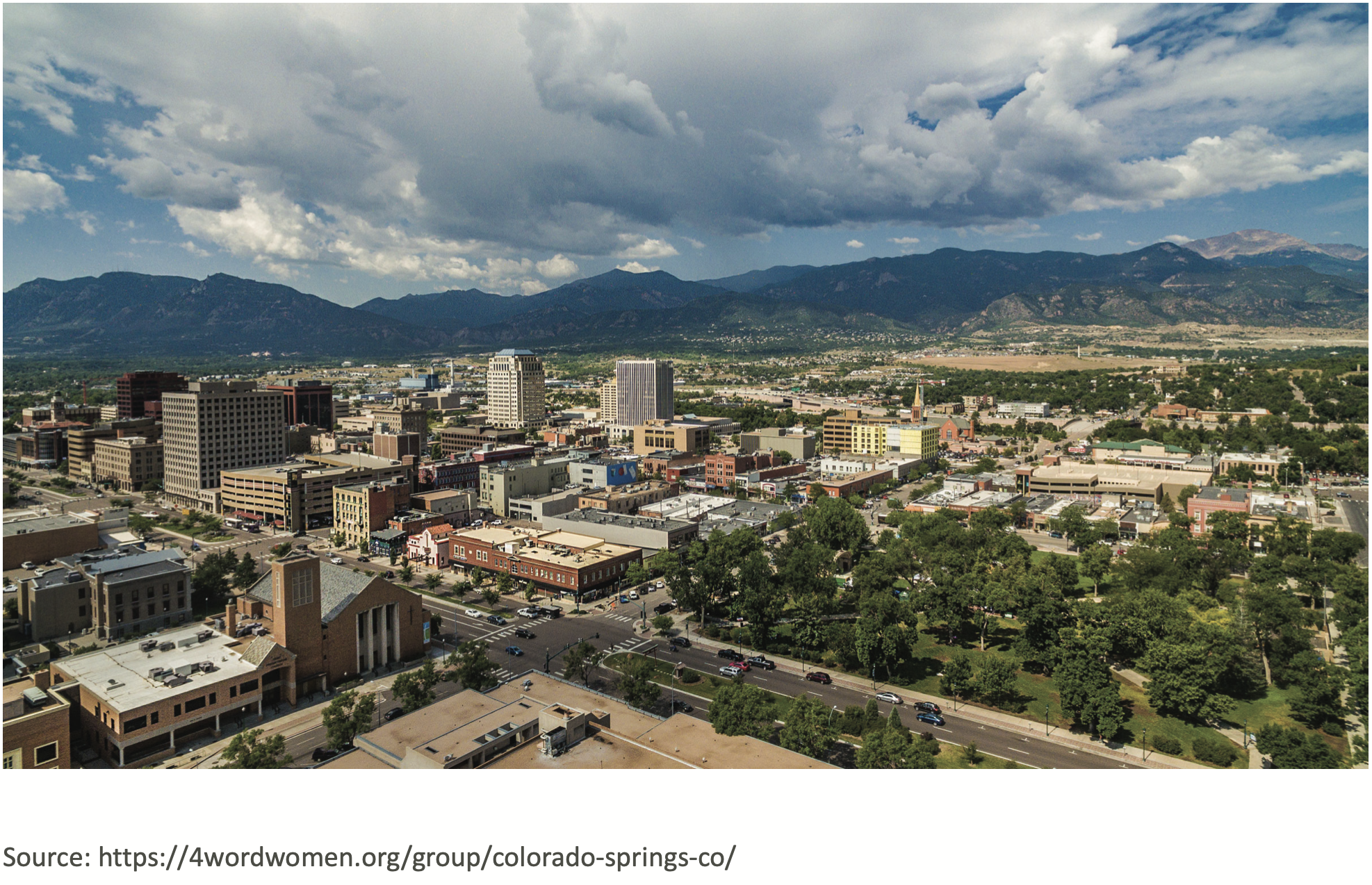

While Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Nashville, Tennessee, have been viewed as evangelical bastions and bellwethers since the 1990s, the changing fortunes of evangelicalism in much of the U.S. have also been reflected in the changing religious makeup of these cities. But in two separate articles profiling the cities, Christianity Today magazine (July/August) notes how evangelicals’ culturally and institutionally changed situation has not necessarily meant a loss of influence. Liam Adams writes that in Colorado Springs, where many evangelical institutions relocated during the 1990s, the days of imposing wide-ranging political change and winning the culture wars have passed. The most influential evangelical group to make its home there was the new Christian Right powerhouse Focus on the Family, which turned its activism to city politics and led an initiative (Amendment 2) to restrict gay rights. Liberal opponents often condemned such efforts as attempting to declare a Christian agenda for the city. The city was also the planting ground for the nations’ leading megachurches, most notably New Life, founded by Ted Haggard. While Haggard was not an activist, he celebrated evangelical (and his own) access to the Bush White House.

Over 20 years later, much of the evangelical activist current has lost its charge and megachurch and other congregations have redirected their influence toward social service and community outreach. Since founder James Dobson left Focus on the Family in 2010, the organization has become less focused on culture war issues in the city and nationally. Haggard’s dramatic fall from grace, under accusations of drug use and visiting a male prostitute, hastened a turning point for New Life to undertake serious community development efforts, including building an apartment complex for 800 single mothers. Church leaders of the prominent First Presbyterian Church said members grew quarrelsome during the culture wars, and like other congregations they have tried to find common ground with their neighbors. Though the city is still a Republican stronghold demographically, non-evangelicals also see evangelicals as shifting toward the moderate middle, Adams writes. Meanwhile, in Nashville the evangelical presence is still growing, with ministries relocating there regularly. The city and the surrounding region have shifted from a Southern Baptist hub to a non-denominational center, much as evangelicalism has taken on a non-denominational flavor.

While several denominations still have offices in Nashville, including the SBC, the United Methodists, the National Baptist Convention, and the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the newcomers flooding into the city do not particularly care about denominational identities or labels, writes David Roach. Non-denominational and “community churches” have proliferated. The $200 million Educational Media Foundation, which owns the K-LOVE and Air1 radio networks as well as publishing, film, and podcast enterprises, recently relocated to Nashville from Northern California. The city’s non-denominational tone has also been influenced by its prominent contemporary Christian music industry. “As album sales soared, the Christian music industry came to employ more Nashvillians than the country music industry,” Roach writes. But denominational enterprises such as Belmont University, the United Methodist publisher Cokesbury, and the SBC’s Lifeway Christian Resources have either disaffiliated or faded. Roach adds that even the city’s historic civil rights advocacy has shed its denominational oversight as white and black leaders “have forged relationships apart from their institutions.”

(Christianity Today, 465 Gundersen Dr., Carol Stream, 60134)