⚫ Among alumni of evangelical schools and homeschooling there appear to be elements of Christian nationalism but also a reluctance to engage in politics, according to research by David Sikkink of the University of Notre Dame. Sikkink analyzed the 2019 Cardus Education Survey of alumni between the ages of 24 and 39 from 1,905 private schools and 400 other schools. He found that graduates of evangelical private schools and those who were homeschooled showed a greater sense of alienation, feeling more than other respondents that the mainstream culture was hostile to them.  There was also lower trust in the mass media and science among this group, although trust in the government was about the same for public and evangelical school alumni but lower for homeschoolers. Homeschoolers were more likely than the other groups to support the exercise of free speech even when considered offensive. Both graduates of evangelical schools and those who were homeschooled showed a greater commitment to local and national than global agendas. They “didn’t feel like citizens of the world,” Sikkink added. But in general there was a reticence to engage in politics among the evangelical and homeschooled groups, especially in the latter population. There was solid support for political conservatism among evangelical school alumni and those who were homeschooled, with the former graduates more likely to support Donald Trump for president than homeschoolers (somewhat unexpected since this group has been assumed to be among the most politicized). Sikkink concluded that there may be elements of nascent Christian nationalism among evangelical school and homeschooled alumni but also a tendency not to be strongly involved in politics, suggesting they may be more involved in family and church life.

There was also lower trust in the mass media and science among this group, although trust in the government was about the same for public and evangelical school alumni but lower for homeschoolers. Homeschoolers were more likely than the other groups to support the exercise of free speech even when considered offensive. Both graduates of evangelical schools and those who were homeschooled showed a greater commitment to local and national than global agendas. They “didn’t feel like citizens of the world,” Sikkink added. But in general there was a reticence to engage in politics among the evangelical and homeschooled groups, especially in the latter population. There was solid support for political conservatism among evangelical school alumni and those who were homeschooled, with the former graduates more likely to support Donald Trump for president than homeschoolers (somewhat unexpected since this group has been assumed to be among the most politicized). Sikkink concluded that there may be elements of nascent Christian nationalism among evangelical school and homeschooled alumni but also a tendency not to be strongly involved in politics, suggesting they may be more involved in family and church life.

⚫ Aging in Western populations may have the result of slowing the rate of secularization, according to a study in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (online in July). Researchers Sergey Shulgin, Julia Zinkina and Andrey Korotayev analyzed data from five waves of the World Values Survey (1981–2014). Their analysis looked at various measures of religiosity in high-income nations, such as church  attendance and self-reports on the importance of religion, and found that in all cases individuals were more likely to be more religious as they aged. The cohort or generational effect was found to be less significant in predicting religiosity than age. “It is mainly in the developed countries that global aging may have the most pronounced effect on slowing down the transition from religious to secular values or, possibly, even on some increase in religiosity,” the researchers write. There are already signs of this effect in countries that have advanced the most in aging, such as Japan.

attendance and self-reports on the importance of religion, and found that in all cases individuals were more likely to be more religious as they aged. The cohort or generational effect was found to be less significant in predicting religiosity than age. “It is mainly in the developed countries that global aging may have the most pronounced effect on slowing down the transition from religious to secular values or, possibly, even on some increase in religiosity,” the researchers write. There are already signs of this effect in countries that have advanced the most in aging, such as Japan.

(Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, https://brill.com/view/journals/jra/jra-overview.xml)

⚫ Pro-choice and pro-life attitudes around the world are shaped by laws on abortion that are in turn influenced by dominant faith traditions, with mainline Protestantism promoting the most liberal views and Islam the most conservative ones, according to a study by sociologist Amy Adamczyk. In a paper presented at the recent meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion in New York, Adamczyk analyzed the World Values Survey (waves 4–6) on country-level attitudes towards abortion across 17 nations.  “While people from nations dominated by mainline Protestant faiths have the most liberal attitudes, residents of Muslim nations have the most conservative views,” she said. But the effect of moral communities, meaning the values and norms created by religions, on abortion attitudes was not found to be significant at the country level. Views on life issues and sexual morality did help explain individual religious influences, and personal religious importance had a greater influence on abortion attitudes in richer rather than poorer countries. But it was the laws allowing for or restricting abortion that had the strongest independent effect on these attitudes, Adamczyk concluded.

“While people from nations dominated by mainline Protestant faiths have the most liberal attitudes, residents of Muslim nations have the most conservative views,” she said. But the effect of moral communities, meaning the values and norms created by religions, on abortion attitudes was not found to be significant at the country level. Views on life issues and sexual morality did help explain individual religious influences, and personal religious importance had a greater influence on abortion attitudes in richer rather than poorer countries. But it was the laws allowing for or restricting abortion that had the strongest independent effect on these attitudes, Adamczyk concluded.

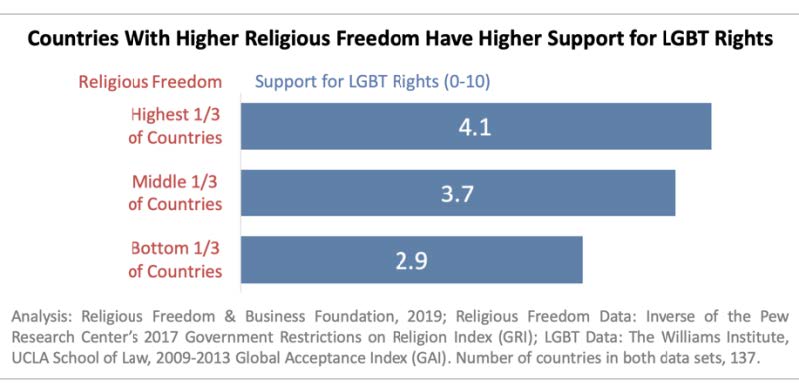

⚫ Rights regarding religious freedom and the LGBT community in the U.S. “seem to rise and fall together,” even though they are often opposed to each other in the culture wars, according to a new study by the Religious Freedom & Business Foundation (August 17). Researcher Brian Grim looks at the intersection between religious freedom and LGBT rights by using global religious freedom measures calculated from data gathered by the Pew Research Center and comparing them with public opinion data on LGBT rights from around the world put together by the Williams Institute, a UCLA Law School think tank.  Grim finds that among the 137 countries that have both religious freedom and LGBT data, “the average level of support for LGBT rights is 38 percent higher in countries with higher religious freedom than in countries with low levels of religious freedom. In the third of countries scoring the highest on religious freedom, the level of support for LGBT rights was 4.1 [on a Global Acceptance Index (GAI) scale of 0–10] compared with only 2.9 in the third of countries scoring at the bottom of the scale on religious freedom.” The level of support for LGBT rights is significantly more likely to be expanding in religiously free countries than in those nations restricting religion. Among the 25 countries with the highest levels of religious freedom, the LGBT GAI increased by 0.11 points between 2004 and 2013. In contrast, among the countries with the worst record on religious freedom (the lowest 12), the GAI decreased on average by 0.53 points. The average level of religious freedom is 36 percent higher in the countries with higher levels of support for LGBT rights than in those with low levels of support for these rights.

Grim finds that among the 137 countries that have both religious freedom and LGBT data, “the average level of support for LGBT rights is 38 percent higher in countries with higher religious freedom than in countries with low levels of religious freedom. In the third of countries scoring the highest on religious freedom, the level of support for LGBT rights was 4.1 [on a Global Acceptance Index (GAI) scale of 0–10] compared with only 2.9 in the third of countries scoring at the bottom of the scale on religious freedom.” The level of support for LGBT rights is significantly more likely to be expanding in religiously free countries than in those nations restricting religion. Among the 25 countries with the highest levels of religious freedom, the LGBT GAI increased by 0.11 points between 2004 and 2013. In contrast, among the countries with the worst record on religious freedom (the lowest 12), the GAI decreased on average by 0.53 points. The average level of religious freedom is 36 percent higher in the countries with higher levels of support for LGBT rights than in those with low levels of support for these rights.

(This report can be downloaded from: https://religiousfreedomandbusiness.org/2/post/2019/08/new-global-study-do-religious-freedom-and-lgbt-rights-have-common-ground.html)

⚫ Being from a Catholic country seems to provide an inoculation against voting for parties skeptical about European Union membership, while Protestant nations are much more likely to be hosts for party politics critical of the EU, according to a study by Margarete Scherer of Goethe University. In the journal Politics and Religion (online in August), Scherer notes that Europe has long been divided between Protestant nations that have emphasized the nation-state and Catholic nations that have been more supportive of internationalism. In analyzing data from the 2014 European Parliament elections, she confirmed the finding that countries with a Catholic background tend to vote for pro-EU parties while Protestant nations tend to vote for anti-EU parties. The more unexpected finding was that the Catholic background would not even seem to “provide a public sphere where European attitudes are related to a Europe-related vote choice…What is new from this study is the claim that Protestantism drives EU issue voting, while Catholicism limits it,” Scherer writes. In predominantly Catholic countries, it doesn’t make a difference whether voters oppose or support an open policy of immigration or agree or disagree on a transfer of competencies to the European level; they are still not likely to vote for an anti-EU party.

(Politics and Religion, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-religion)

⚫ A study of megachurches in the Netherlands finds a pattern of growth, although such expansion is due largely to a “circulation of the saints,” that is, an addition of those who are already religious. The study, presented by Paul Vermeer of Radboud University at the mid-August meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion in New York, examined six thriving evangelical megachurches (having over 1,000 attendees) whose recent history has been characterized by sometimes spectacular growth: a Nazarene church, two Baptist churches, an evangelical church mainly attended by people from Surinam and the Netherlands Antilles, and two free evangelical churches with ties to Willow Creek. Although not representative of the entire evangelical population of the Netherlands, the 584 attenders of these churches Vermeer examined through an online survey closely matched demographic features of evangelicals, including their high-income status.

Vermeer found that the evangelical congregations he studied were exceptional compared to mainline and Catholic churches for the high rate of switching, with only 20.4 percent of their current membership having also belonged to an evangelical congregation during adolescence. New members were more likely to come from mainline Protestant (26.9 percent) and orthodox Protestant (24.4 percent) churches, and even from secular ranks (25.7 percent), than from evangelical congregations.  There were few from Catholic backgrounds (2.6 percent). Secular converts differed from stable church members in that they had a more “intrinsic religious orientation” (with a religious upbringing) and were also more likely to have a partner who switched or converted to an evangelical congregation as well. Vermeer concludes that the growth of these congregations is “both a matter of religious switching and of successfully reaching out to the unchurched…In short, these evangelical congregations basically attract religious people. But if this is how religious congregations can withstand the secularizing forces in secular Dutch society, there are also clear limits to their success and ability to grow.”

There were few from Catholic backgrounds (2.6 percent). Secular converts differed from stable church members in that they had a more “intrinsic religious orientation” (with a religious upbringing) and were also more likely to have a partner who switched or converted to an evangelical congregation as well. Vermeer concludes that the growth of these congregations is “both a matter of religious switching and of successfully reaching out to the unchurched…In short, these evangelical congregations basically attract religious people. But if this is how religious congregations can withstand the secularizing forces in secular Dutch society, there are also clear limits to their success and ability to grow.”