- While voting patterns among religious believers have held steady in recent elections, there was less support for President-elect Donald Trump among Protestants compared to 2020. RW was going to press as the election results came out, and we will undoubtedly report more on the election and the upcoming Trump presidency in the next issue. In a post on X (November 5), political scientist Ryan Burge finds that the distribution of votes for Trump among several religious groups remains similar to that of four years ago—with 59 percent of Protestants, 52 percent of Catholics, and 66 percent of Mormons voting for him. Trump had the lowest votes among Jews (31 percent), Muslims (30 percent), and “Nones” (27 percent). However, the Muslim vote for Trump in 2020 was only 6 percent. In his Substack newsletter Rational Sheep (November 8), Terry Mattingly notes that the declining Protestant vote for Trump, which was 64 percent in 2020, may be due to a weakening of support among mainline Protestants, since the president-elect’s totals among white evangelical voters remained about the same (at 82 percent).

Source: First Liberty (https://firstliberty.org/news/religious-voters-deciding-factor-in-2024-election/).

(Ryan Burge on X,

https://x.com/ryanburge/status/1853978633796256212utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email)

- Church closures tend to follow different patterns in urban and suburban areas, with closed urban churches often being used for secular purposes and suburban congregational properties more often being purchased by other religious groups. Those are two of the findings that were reported in papers on church closures at the meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in late October. Kraig Beyerlein of the University of Notre Dame introduced this increasingly pressing issue by looking at urban churches in Chicago, noting that conflicting counts of congregations make it difficult to estimate church closures, with many congregations relocating instead of closing. He noted that approximately half of the 4,907 congregations counted in Chicago in 2002 have survived at their original sites. As to the uses of closed congregations, Beyerlein found that the majority were slated for non-religious purposes, ranging from ordinary businesses to a circus school. Of the denominations that experienced closures, the Catholic Church had the fewest closings and non-affiliated congregations the most, with black churches and Hindu and Muslim congregations in the middle. The variation is mostly due to the age of congregations. He also found the predominance of black and Latino churches to be a predictor for the changing use of land.

Source: James K. Honig (https://jameskhonig.com/2015/09/24/lament-at-the-closing-of-a-church/)-

Another paper by Brian Miller of Wheaton College looked at church closures in the Chicago suburbs, finding the pattern to be very different from urban areas. Of the 725 congregations in Dupage County, 87 congregations have closed, with the majority being sold to other religious groups. Miller found that Baptist and Christian Science churches, congregations with an early establishment in the suburbs, had closing rates of 67 percent and 100 percent, respectively. Twelve had closed by 2023. Other predictors of church closures included a larger number of congregations in the areas to start with, and the age of the communities in which they were located. Miller concluded that it was a challenge counting closures, since some churches may appear active but have actually relocated or are closed.

Source: McCormick Theological Seminary.

- Christian seminaries are becoming more pluralistic, with more non-denominational and non-affiliated as well as non-Christian students, according to a paper presented at this year’s meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. Kristina Lizardy-Hajbi of Iliff Theological Seminary analyzed data from the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) between 2001 and 2024. She found that the denominations represented in these seminaries had grown from 112 to140, with an increase of 23 schools since 2001. Among Christian students, there has been an increasing share of evangelicals in these seminaries (from 40 to 46 percent) and a decreasing share of mainline Protestants (from 38 to 33 percent), while the share of Catholics and Eastern Orthodox has remained the same (at 21 percent). There has been a 40-percent increase in the “other” category, which includes interdenominational Christians as well as Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, non-denominational, and non-affiliated students, increasing from 19 to 33 percent of the total. Lizardy-Hajbi found that Christians decreased from 80 to 67 percent of all students, suggesting growth in those “other” categories besides non-denominational Christians. But, parsing these categories, she found that there has been a sharp increase in non-denominational students in evangelical seminaries, while multi-denominational and interdenominational students have decreased. It was among mainline seminaries that Lizardy-Hajbi found Muslim, Jewish, and Buddhist growth (by more than 400 percent, from 53 to 272 students), with only one Buddhist student found in evangelical seminaries.

Source: Wyoming Seminary (https://www.wyomingseminary.org/campus-life/diversity-equity-inclusion-andbelonging).

- Polyamory, the practice of having open sexual or romantic relationships with more than one person at a time, is gaining a place in progressive churches, though congregational settings are often the last places polyamorists will “come out to.” At the recent conference of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, April Stace of General Theological Seminary presented findings from her ethnographic study of a small number of polyamorists, totaling 16 participants. She noted that estimates of those practicing polyamory vary widely, ranging from 4 to 20 percent of Americans. Although hers was a non-representative sample, Stace found that most of the participants, while having a background in evangelical purity culture, came from mainline Protestantism. Five of the 16 were in the ordination process.

Source: Center for Faith, Sexuality & Gender (https://www.centerforfaith.com/blog/a-response-to-the-critics-ofmy-ct-article-on-polyamory

The Bible was often cited and was seen as legitimizing their lifestyle. The participants saw community as an important Christian value that was often expressed in networks of other polyamorous Christians offering each other support. They also valued “faithfulness,” though not in a monogamous sense but as being “faithful to oneself” in “honest and caring relationships,” according to Stace. Yet this honesty and support was rarely found in wider congregational settings. In fact, congregations were often the last places that these polyamorous Christians “came out to” regarding their lifestyle, with only three participants having done so. Few experienced any shunning for their polyamory, but most agreed that the church needed to be more robustly “sex-positive,” and a place that is safe from abuse.

- Chile is showing a decline in Catholicism while evangelicals are holding steady, according to the results of the new national public opinion survey by the Centre for Public Studies (CEP). The newsletter Evangelical Focus (October 19) reports the survey showing that 17 percent of Chileans define themselves as evangelical. The number of evangelical believers coincides with the number of those who were raised in this faith, and the evangelical faith “remains stable in quantitative terms. But of the 74 percent of citizens raised in the Catholic faith, only 48 percent of adults said they maintain the same faith.” The survey showed 76 percent of respondents saying they believe and have always believed in God, which is a slight decline from the 80 percent found in the 2018 survey. A considerable 31 percent consider themselves agnostic or atheist. Among other religions identified, 1 percent of respondents identified as Mormon, 1 percent Jehovah’s Witness, and 1 percent “other” religion or creed, while 1 percent answered that they “don’t know or no answer,” and 6 percent identified as “none.” None of the respondents identified as Muslim or Jewish.

(Evangelical Focus, https://evangelicalfocus.com/world/28583/17-of-chileans-identify-as-evangelicals)

- While there has been significant progress in religious freedom in Latin America, it has not been uniform, with some countries still lacking specific laws to protect and promote religious freedom and not having the clear leadership to drive successful policies in this area. Writing in the Canopy Forum on the Interaction of Law and Religion (September 26), Camila Sánchez Sandoval analyzes the expansion of the right to religious freedom in Latin America at the constitutional level, finding that 25 percent of the region’s national constitutions, including Argentina’s, Costa Rica’s, Guatemala’s, Panama’s, and Uruguay’s, still favor the Catholic religion, either as the official religion or through economic benefits. However, all countries grant the right to freedom of worship and protection against religious discrimination. Additionally, half of the countries—Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, and Paraguay—prohibit political participation by clergy. Only the countries of Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Venezuela recognize the beliefs of indigenous peoples. At the statutory level, Sandoval finds that only 8 out of 20 Latin American countries—Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, and Peru—have at least one specific law promoting religious freedom.

In some countries, such as Colombia and Peru, laws differentiate which religious beliefs are protected, excluding practices such as witchcraft or occultism. Regarding the registration of religious entities, 12 countries—Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Venezuela—have religious entity registries and an entity responsible for granting legal status to churches. This could be viewed as a form of religious discrimination, contradictory to constitutional principles. Sandoval concludes that “existing laws extend what is established in constitutions but lack concrete actions, programs, or strategies to guarantee or strengthen this right.” Colombia stands out for its comprehensive public policy on religious freedom and worship. “…[W]hen reviewing the national development plans (PNDs) of current presidents in 20 Latin American countries, religious freedom is mentioned in only [six] of these plans. Chile, Colombia, and Nicaragua are the only countries that detail concrete actions to strengthen this right [even as Nicaragua is facing charges of religious persecution by international human rights organizations].”

(Canopy Forum, https://canopyforum.org/2024/09/26/normative-development-of-religious-freedom-in-latin-america-counter-transfer-of-religious-policies/)

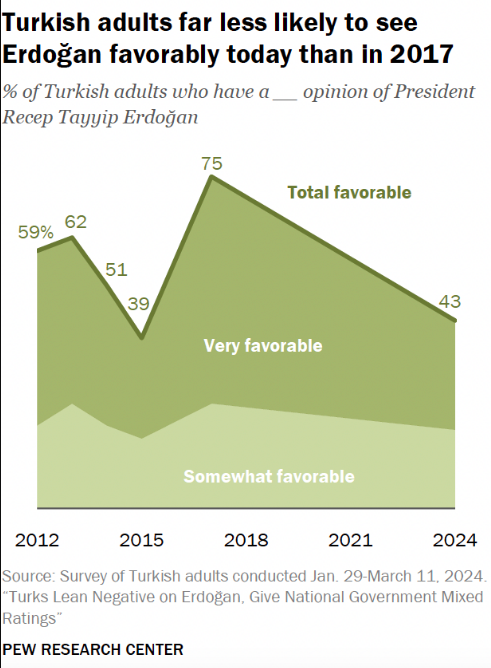

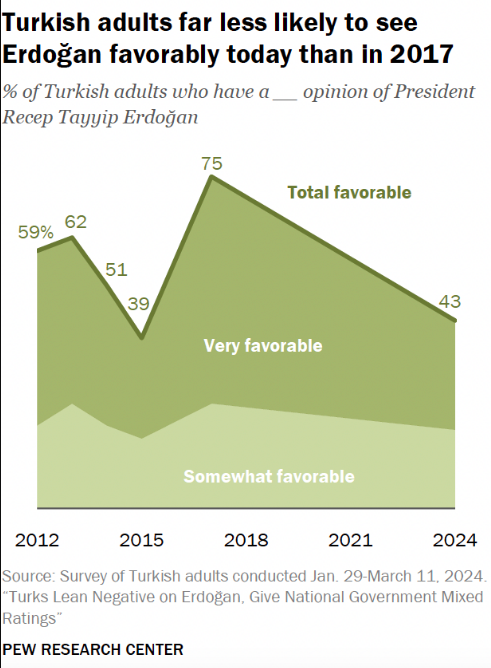

The frequency of prayer among Muslims in Turkey is related to their views on numerous public issues, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. The survey found that trust in the government is significantly higher among Muslims who observe the five-prayers-a-day ritual compared with those who pray less often. Among Muslims who say the five prayers daily, 69 percent say that they trust the national government to do what is right for their country, compared with 40 percent of those who pray at least weekly and 26 percent who pray less than weekly. More frequently praying Muslims are more likely to see Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in a positive light and the way democracy is working in their country. Those who pray more infrequently are more likely to support Turkey becoming a member of the European Union. Overall, 55 percent of Turkish adults have an unfavorable opinion of Erdoğan while 43 percent have a favorable opinion, a substantial drop from a 75 percent favorability rate in 2017. The 2017 survey was conducted eight months after Erdoğan and his government survived a coup attempt by a faction of the military.

The frequency of prayer among Muslims in Turkey is related to their views on numerous public issues, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. The survey found that trust in the government is significantly higher among Muslims who observe the five-prayers-a-day ritual compared with those who pray less often. Among Muslims who say the five prayers daily, 69 percent say that they trust the national government to do what is right for their country, compared with 40 percent of those who pray at least weekly and 26 percent who pray less than weekly. More frequently praying Muslims are more likely to see Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in a positive light and the way democracy is working in their country. Those who pray more infrequently are more likely to support Turkey becoming a member of the European Union. Overall, 55 percent of Turkish adults have an unfavorable opinion of Erdoğan while 43 percent have a favorable opinion, a substantial drop from a 75 percent favorability rate in 2017. The 2017 survey was conducted eight months after Erdoğan and his government survived a coup attempt by a faction of the military.

(The Pew study can be downloaded from: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2024/10/16/turks-lean-negative-on-erdogan-give-national-government-mixed-ratings/)

- When accounting for multiple religious identities and beliefs, the rates of religiosity in Asian countries and societies, such as Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, and Japan, show a degree of change and growth, according to several recent studies. In a paper presented at the late-October meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, which RW attended, Purdue University sociologist Fenggang Yang introduced preliminary findings from his project, Global East Religiosity, which has added measures that allow respondents to indicate multiple religious identities, in contrast to the standard method of having them select only one religion. Allowing for such an option in surveys fits better with the eclectic and ritual-based approach of Asians when it comes to religions, and survey results from the above Asian countries suggest that this methodological change makes a difference. Yang said that the pattern of multiple religious ties may be similar to Kamala Harris’s religious identity, as she claims belonging and engaging in Hindu, Baptist, and even Jewish practices and traditions.

Main Hall of the Mengjia Longshan Temple in Taipei, Taiwan (source: Bernard Gagnon, 2011, Wikimedia Commons -https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Longshan_Temple,_Taipei_01.jpg).

In a paper on Japan presented at the conference, Natsuko Godo of Purdue found in his survey of 3,947 respondents that Christians didn’t distinguish between Protestant and Catholic and that fortune telling was practiced by about half of his sample, including those who said they had no religion. Only 20 percent of the respondents chose Shinto alone as their religion, 33 percent folk religion alone, and 8 percent Confucianism alone. In a survey of 3,000 Taiwanese, Charles Chang of Duke Kunshan University found that half of his sample’s “nones” engaged in religious rituals, and 19 percent of the sample chose more than one religion.

The frequency of prayer among Muslims in Turkey is related to their views on numerous public issues, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. The survey found that trust in the government is significantly higher among Muslims who observe the five-prayers-a-day ritual compared with those who pray less often. Among Muslims who say the five prayers daily, 69 percent say that they trust the national government to do what is right for their country, compared with 40 percent of those who pray at least weekly and 26 percent who pray less than weekly. More frequently praying Muslims are more likely to see Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in a positive light and the way democracy is working in their country. Those who pray more infrequently are more likely to support Turkey becoming a member of the European Union. Overall, 55 percent of Turkish adults have an unfavorable opinion of Erdoğan while 43 percent have a favorable opinion, a substantial drop from a 75 percent favorability rate in 2017. The 2017 survey was conducted eight months after Erdoğan and his government survived a coup attempt by a faction of the military.

The frequency of prayer among Muslims in Turkey is related to their views on numerous public issues, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. The survey found that trust in the government is significantly higher among Muslims who observe the five-prayers-a-day ritual compared with those who pray less often. Among Muslims who say the five prayers daily, 69 percent say that they trust the national government to do what is right for their country, compared with 40 percent of those who pray at least weekly and 26 percent who pray less than weekly. More frequently praying Muslims are more likely to see Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, in a positive light and the way democracy is working in their country. Those who pray more infrequently are more likely to support Turkey becoming a member of the European Union. Overall, 55 percent of Turkish adults have an unfavorable opinion of Erdoğan while 43 percent have a favorable opinion, a substantial drop from a 75 percent favorability rate in 2017. The 2017 survey was conducted eight months after Erdoğan and his government survived a coup attempt by a faction of the military.