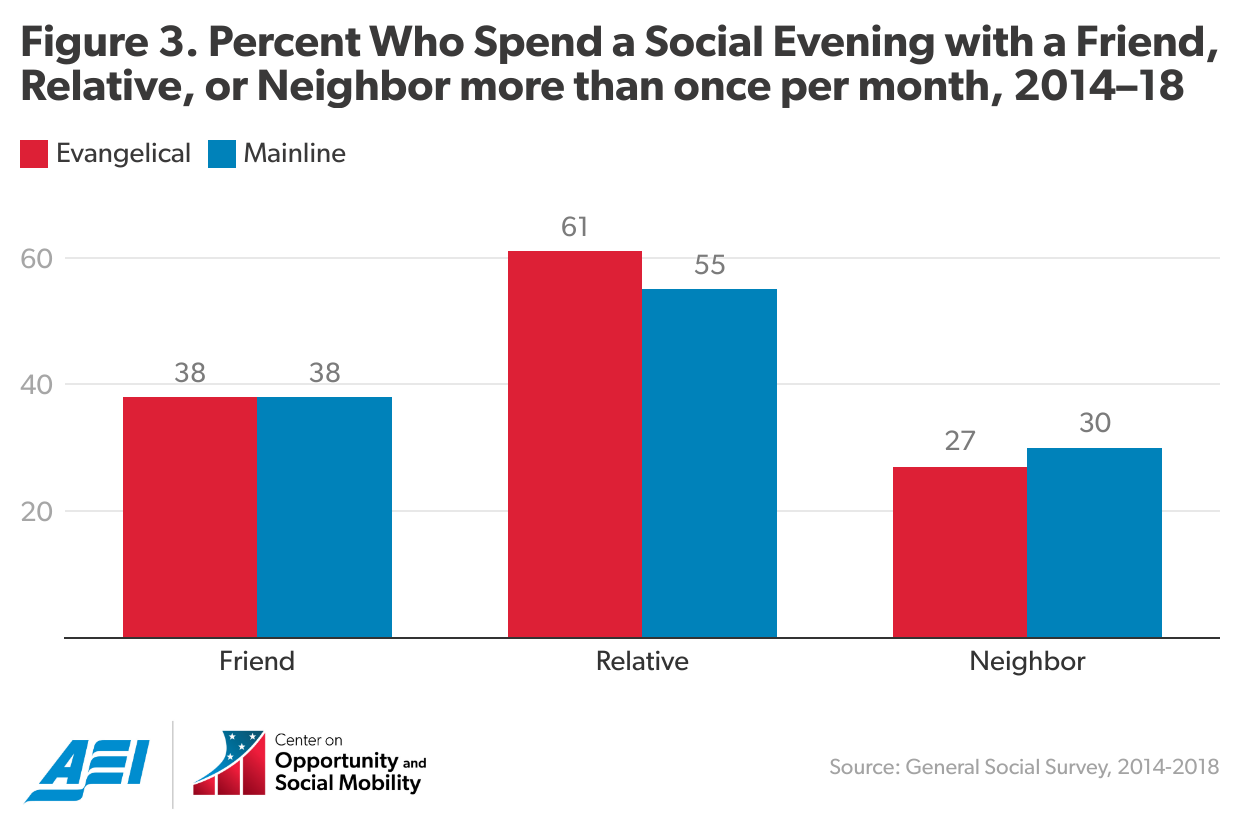

These relationships were seen more strongly at the country level. Counties with higher shares of LDS and mainline Protestants also tended to have the highest levels of social capital, “suggesting that there may be something unique about these religious traditions that encourages social capital development in communities,” Winship and O’Rourke write. They argue that the more public orientation of mainline Protestantism has influenced the pro-social attitudes of adherents and other residents. In contrast, while evangelicals are more likely to attend church than their mainline counterparts, helping them to build social capital through such participation, they tend to concentrate this social energy within their congregations rather than engaging the wider community. Even with regard to family unity, where evangelicals have been strong advocates, these conservative Protestants tend to have weaker family bonds, with more divorce than mainline Protestants.

These relationships were seen more strongly at the country level. Counties with higher shares of LDS and mainline Protestants also tended to have the highest levels of social capital, “suggesting that there may be something unique about these religious traditions that encourages social capital development in communities,” Winship and O’Rourke write. They argue that the more public orientation of mainline Protestantism has influenced the pro-social attitudes of adherents and other residents. In contrast, while evangelicals are more likely to attend church than their mainline counterparts, helping them to build social capital through such participation, they tend to concentrate this social energy within their congregations rather than engaging the wider community. Even with regard to family unity, where evangelicals have been strong advocates, these conservative Protestants tend to have weaker family bonds, with more divorce than mainline Protestants.

(The study can be downloaded here: https://www.aei.org/articles/the-mainline-protestant-ethic-and-the-spirit-of-social-capitalism/)

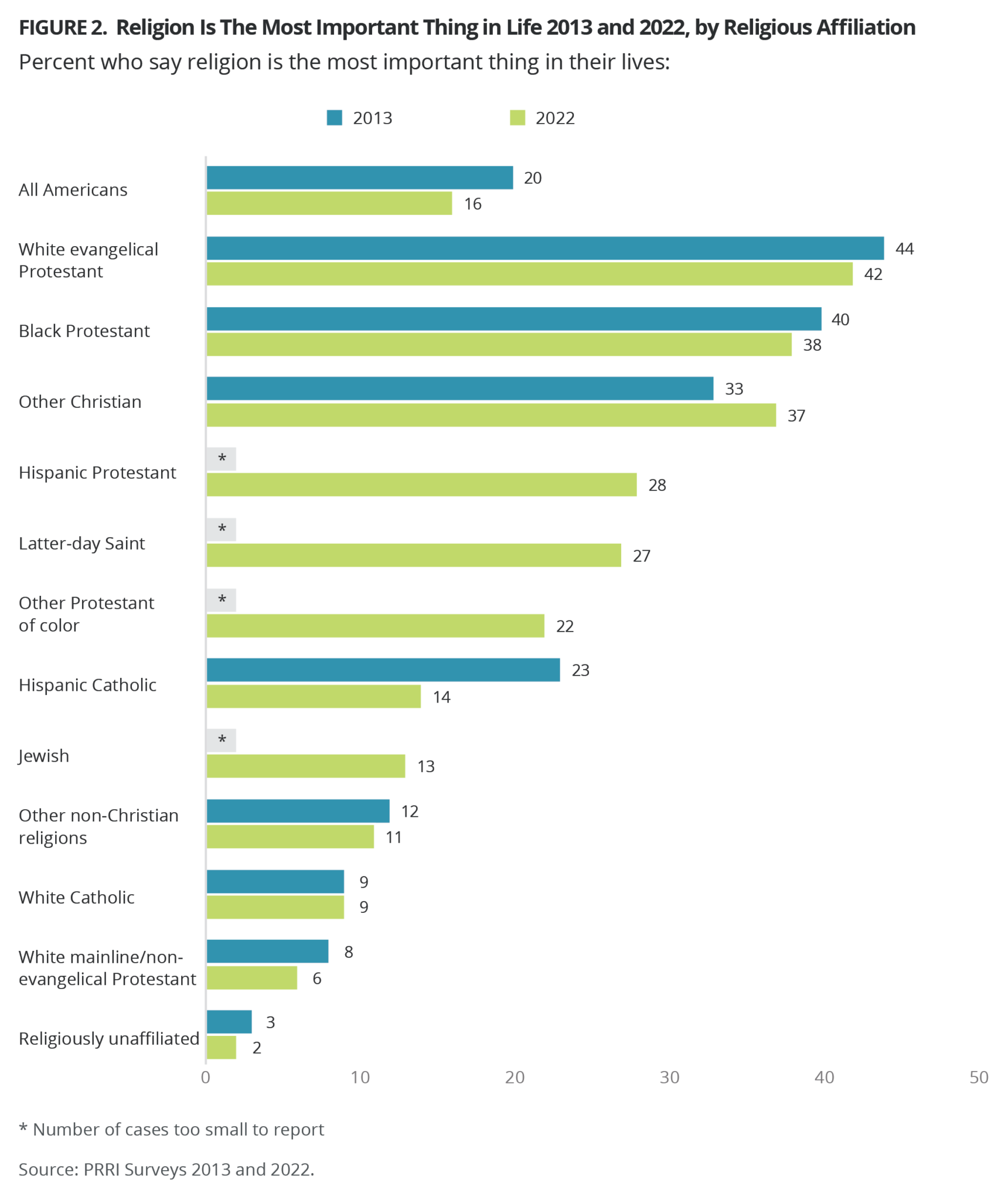

The rate of people who say that religion is the most important thing in their lives has decreased from 20 percent in 2013 to 16 percent today. Nearly 3 in 10 say religion is not important to them at all, which is up from 19 percent 10 years ago. The PRRI survey of 5,872 American adults finds that 57 percent seldom or never attend religious services (compared with 45 percent in 2019). There is also a higher degree of congregational switching taking place, with 24 percent of Americans saying they now belong to a religious congregation other than the one they grew up in—an increase of eight percentage points from 2021. But an overwhelming number of regular attenders (82 percent) state they are optimistic about the future of their congregation, with 89 percent saying they are proud to be associated with their church.

The rate of people who say that religion is the most important thing in their lives has decreased from 20 percent in 2013 to 16 percent today. Nearly 3 in 10 say religion is not important to them at all, which is up from 19 percent 10 years ago. The PRRI survey of 5,872 American adults finds that 57 percent seldom or never attend religious services (compared with 45 percent in 2019). There is also a higher degree of congregational switching taking place, with 24 percent of Americans saying they now belong to a religious congregation other than the one they grew up in—an increase of eight percentage points from 2021. But an overwhelming number of regular attenders (82 percent) state they are optimistic about the future of their congregation, with 89 percent saying they are proud to be associated with their church.

(The PRRI study can be downloaded here: https://www.prri.org/research/religion-and-congregations-in-a-time-of-social-and-political-upheaval/)

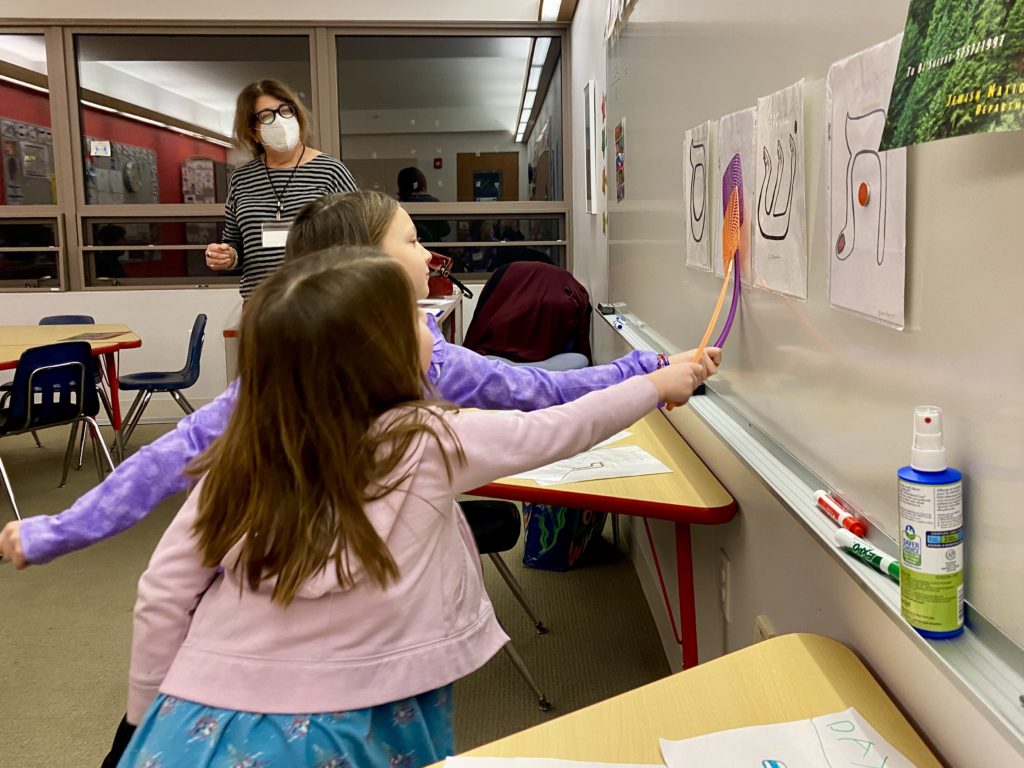

Source: Kerem Shalom.

A growing number of combined Reform and Conservative schools responded to the survey, although they tend to be smaller on average than either Reform or Conservative schools. The Reform movement has, on average, the most schools when compared to other movements. Reform schools are also, on average, the largest by enrollment. More than half of all students who enroll in a Hebrew school do so at a Reform school—or even more if the joint Reform and Conservative programs are counted. Although there are very few (52) schools that have over 300 students, the 20 largest schools nationwide are all Reform. When compared with the enrollment data from the 2006–2007 census, there are very few schools significantly larger now than they were 15 years ago. The decrease in students is proportionately larger than the decrease in schools, although the average school size has also decreased, and every single grade is, on average, smaller. Bar and Bas Mitzvah ceremonies remain a point of “graduation” from supplementary schools, with just shy of about 50 percent of eligible students in 6th and 7th grade enrolling, and less than 20 percent in all grades 8th and beyond. But when asked, most survey respondents said that the most important purpose of supplementary schools was to foster students’ sense of belonging to the Jewish people.

(The Hebrew school study can be downloaded from: patways.jewishedproject.org)

Source: SIM By Prayer.

(International Bulletin of Mission Research, https://journals.sagepub.com/home/ibm)