Source: Bill of Health.

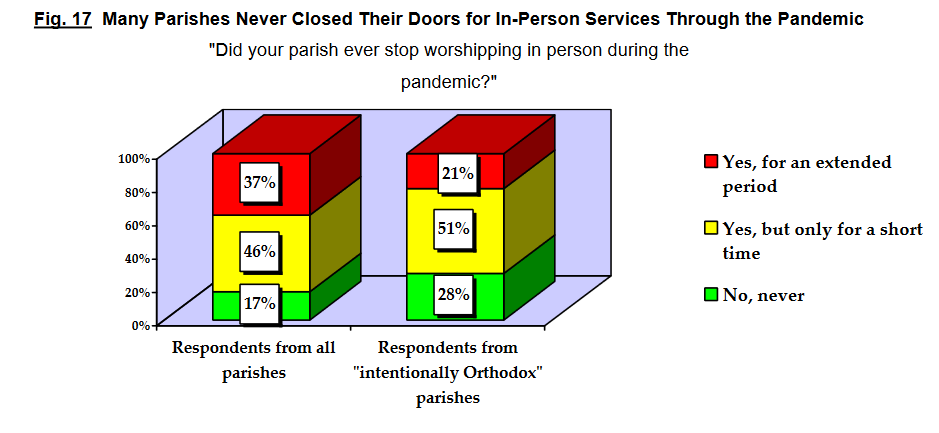

Most of the congregations wanted in-person worship, particularly their younger members (with 87 percent of younger parishioners wanting in-person worship compared to 78 percent of middle-aged and 69 percent of older members). This suggests that “online worship has little future in Orthodox churches,” Krindatch said. He also found that faith and trust in clergy grew during the pandemic but that such attitudes declined in regard to bishops and their control of parishes. There was also a growth in optimism among members about working together and common decision-making in parishes. Yet, like most other congregations, there was continuing decline among youth.

(Krindatch’s report can be downloaded here: https://orthodoxreality.org/coronavirus-and-american-orthodox-parishes/)

Source: Orthodox Reality.

Mirriam Seddiq created American Muslim Women Political Action Committee to help elect leaders who will advocate for Muslim women’s rights. (Source: Noel St. John/National Press Club – Middle East Eye)

Source: Picryl.

Most Catholic universities and colleges are not following in the path of secularization trodden by their Protestant counterparts, even though the future of Catholic schools has shifted from the hands of religious orders to those of the laity. In a study of Catholic higher education published in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (online in November), Baylor University researchers Perry Glanzer, Jessica Martin, Theodore Cockle and Scott Alexander measured the Catholic identity of colleges according to an Operationalizing Faith Identity Guide (OFIG) that they created, including such criteria as the presence of Catholic Mass, requiring the president to be Catholic, having centers and institutes related to religion and Catholicism, a statement of faith, and required theology courses. They found that the majority of Catholic colleges and universities have maintained some affiliation with the Catholic Church, that not one Catholic institution of the 181 studied was completely secular, and that all of them referred to their Catholic identity in their mission statements. In that, these institutions are very different from Protestant schools, 83 of which the researchers found to have no relation to their sponsoring churches.

Many of the Protestant colleges and universities occupied the extremes of the OFIG, either being largely secular or religious. In contrast, the Catholic schools were more in the middle of the spectrum. They required at least one theology course, had Mass available, and sponsored centers and institutes relating to religion. Yet the researchers found that the majority did not refer to Christian reasoning in their codes of conduct or require two or more Christian courses, and that less than five percent required faculty or staff to be Catholic. The researchers found that the most recent school started by a religious order was in 1965. The loss of the religious orders’ educational vitality has been replaced by lay-led, often conservative colleges that the researchers conclude “perceive that the more hostile higher-education culture requires…more distinctly Christian and separate institutions that maintain the Church’s educational mission and faithfulness.”

10

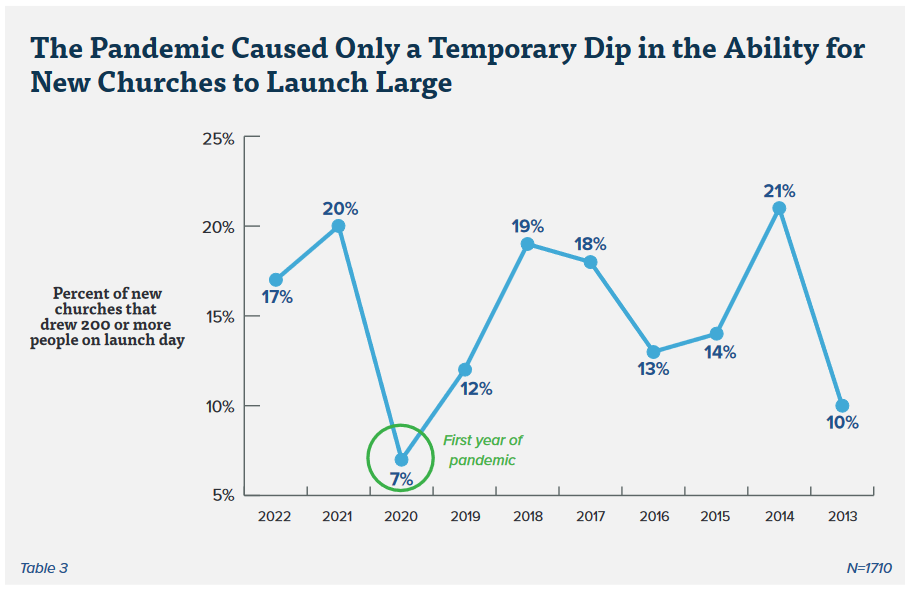

Source: Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability.

An updated longitudinal study of individuals who “deconverted” from their religions finds that they still retain a strong interest in spirituality, even more than those who remained in their faiths. The study, first published in 2009 by German psychologist Hans Streib, followed 272 participants from the U.S. and Germany, some of who (called “traditionalists” or “stayers”) remained in their religions while others were in the deconversion process (“movers”). Streib and a research team tracked down 45 of these interviewees (mostly the German participants this time around) in their new book, Deconversion Revisited (Vandenhoek & Ruprecht), and found that the pattern of the movers claiming a “more spiritual” self-identification had remained stable. There was also a decline in the “more religious than spiritual” identification. At the same time, those who deconverted in the original study showed greater rates of self-acceptance and finding meaning in life, while those deconverting in the second wave of the study showed lower rates of self-acceptance and finding meaning in life. Because of the small number of interviewees, Streib and his research team caution that their findings are not necessarily representative of the larger population of “deconverts.”

Jehovah’s Witnesses’ mobile carts in Venice, Italy, 2019 (Tiia Monto, Wikimedia Commons).

According to the elders, the number of attendees grew because those who had “always been interested but did not want to spend time going to meetings [could] now join by Zoom.” During the pandemic, the number of publishers (or active members) who returned to regular publishing rapidly increased. Some who had been disfellowshipped were reinstated and returned to the organization. Public talks during the meetings were often given by members from other countries and even continents. “As a result,” Tokmantcev noted, “the cohesion of the worldwide JW community that used to be abstract became more tangible and real despite the discontinuation of the local in-person meetings.” Publications and teachings once issued from the Watch Tower Organization became more diverse in origin and nature, including new kinds of music and even TikTok videos. Required hours of “preaching” were maintained through sharing and speaking to friends and family. In short, the “density of practices” associated with being a Witness retained its intensity.

While in 2020, the Jehovah’s Witnesses reported 10,652 publishers in Armenia, in the most recent report from 2021, the organization reported 700 more publishers—the first instance of growth since 2010. Yet at the same time, the number was one of the lowest ever recorded in Armenia. Tokmantcev concluded that digitalization was key in understanding these trends. The Jehovah’s Witness world report shows that in the poorest countries—places where the Internet is accessible to less than 10 percent of the population—the religion lost up to 10 or even 15 percent of its members. “At the same time, the countries with ‘old JW’ communities, such as Great Britain, Armenia, France, and Germany, that used to stagnate in terms of growth, demonstrated impressive growth.”