![]()

A study of 110,000 sermons by over 5,500 American religious leaders finds that they routinely contain political messages, with mainline Protestants most likely to deliver such sermons, with evangelicals’ preaching being far less predictable than expected. The study, conducted by political scientists Constantine Boussalis, Travis Coan, and Mirya Holman, confirms the entanglement between religion and politics in the U.S., including within congregational life, but sheds light on the actual political content of sermons. They note that the sermons studied were posted by pastors on the SermonsCentral and thus is a convenient rather than a random  sample of these sermons. Writing in the journal Politics and Religion (online in July, 2020), the researchers find that 37 percent of the sermons preached by the large sample of clergy in the dataset they collected feature a political subject; 71 percent of the pastors delivered at least one sermon with political content. Among the most popular political topics included the economy, homosexuality, abortion, war, and welfare, with mainline clergy most likely to discuss politics in their sermons. Unexpectedly, evangelicals were not found to be more active in preaching on abortion, nor were they less active on abortion. Mainline pastors were more likely to preach about homosexuality.

sample of these sermons. Writing in the journal Politics and Religion (online in July, 2020), the researchers find that 37 percent of the sermons preached by the large sample of clergy in the dataset they collected feature a political subject; 71 percent of the pastors delivered at least one sermon with political content. Among the most popular political topics included the economy, homosexuality, abortion, war, and welfare, with mainline clergy most likely to discuss politics in their sermons. Unexpectedly, evangelicals were not found to be more active in preaching on abortion, nor were they less active on abortion. Mainline pastors were more likely to preach about homosexuality.

(Politics and Religion, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-religion)

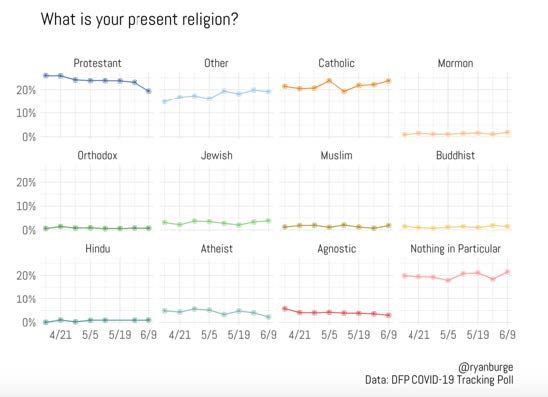

![]() Data tracking religious identification over the course of the pandemic in the U.S. finds a small but steady decrease in people claiming such affiliations, write political scientists Ryan P. Burge and Paul Djupe in the Religion in Public blog (July 7, 2020). The researchers use polling data from Data for Progress between April and June that included questions on religious identification. The surveys find that there has been a five percent drop of people claiming a Protestant identity over the period from April 16 to

Data tracking religious identification over the course of the pandemic in the U.S. finds a small but steady decrease in people claiming such affiliations, write political scientists Ryan P. Burge and Paul Djupe in the Religion in Public blog (July 7, 2020). The researchers use polling data from Data for Progress between April and June that included questions on religious identification. The surveys find that there has been a five percent drop of people claiming a Protestant identity over the period from April 16 to  June 9, 2020. There was no similar drop among Catholics. Burge and Djupe focus on how those no longer claiming a Protestant identification chose the “other” category, suggesting these people have not necessarily left behind a religious identification or even left their Protestant congregations. Just over 50 percent of those choosing the “other” identification were evangelical. They note that the “others” have become 15 percent more Democratic than Republican, while Protestant have become 14 percentage points more Republican. The researchers conclude that the growth of negative views about President Trump may have “taken a bite out of the religious identity of his most fervent supporters—people not on board with Trump’s politics are taking refuge in other religious homes.”

June 9, 2020. There was no similar drop among Catholics. Burge and Djupe focus on how those no longer claiming a Protestant identification chose the “other” category, suggesting these people have not necessarily left behind a religious identification or even left their Protestant congregations. Just over 50 percent of those choosing the “other” identification were evangelical. They note that the “others” have become 15 percent more Democratic than Republican, while Protestant have become 14 percentage points more Republican. The researchers conclude that the growth of negative views about President Trump may have “taken a bite out of the religious identity of his most fervent supporters—people not on board with Trump’s politics are taking refuge in other religious homes.”

(Religion in Public, https://religioninpublic.blog/2020/07/07/are-people-changing-religion-in-the-pandemic/)

![]() It is well known that the coronavirus has disproportionately affected ethnic and racial minorities, but new research in England and Wales reports that this pattern may also include religious minorities, particularly the Jewish community. The newsletter Counting British Religion (July 1, 2020) notes that anecdotal reports and speculation early in the pandemic noted that Jewish,

It is well known that the coronavirus has disproportionately affected ethnic and racial minorities, but new research in England and Wales reports that this pattern may also include religious minorities, particularly the Jewish community. The newsletter Counting British Religion (July 1, 2020) notes that anecdotal reports and speculation early in the pandemic noted that Jewish,  Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh communities had higher rates of mortality from the virus in much of the UK than other groups. The Office of National Statistics recent release of three reports on Covid-19-related deaths from England and Wales from March to May confirms these suspicions. The religion segment of the report links 37,956 Covid-related deaths to religious and other demographic characteristics of the deceased. The study concluded that “For the most part, the elevated risk of certain religious groups is explained by geographical, socio-economic, and demographic factors and increased risk associated with ethnicity. However, after adjusting for the above, Jewish males are at twice the risk of Christian males, and Jewish women are also at higher risk. Additional data and analysis are required to understand this excess risk.”

Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh communities had higher rates of mortality from the virus in much of the UK than other groups. The Office of National Statistics recent release of three reports on Covid-19-related deaths from England and Wales from March to May confirms these suspicions. The religion segment of the report links 37,956 Covid-related deaths to religious and other demographic characteristics of the deceased. The study concluded that “For the most part, the elevated risk of certain religious groups is explained by geographical, socio-economic, and demographic factors and increased risk associated with ethnicity. However, after adjusting for the above, Jewish males are at twice the risk of Christian males, and Jewish women are also at higher risk. Additional data and analysis are required to understand this excess risk.”

(Counting Religion in Britain, http://www.brin.ac.uk/counting-religion-in-britain-june-2020/)

![]() When looking at levels of religiosity rather than religious affiliation, a recent study finds that political corruption tends to be greater in more religious countries. The study, published in the Review of Religious Research (online in July 2020), used data from multiple countries and from different time periods to determine whether religiosity is more important than religious affiliation in relation to corruption. Past studies have found that religious diversity and specific religious traditions might discourage corruption, but little has been done on the degrees of religious devotion in societies and their levels of corruption. Authors Omer Gokcekus and Tufan Ekici look at

When looking at levels of religiosity rather than religious affiliation, a recent study finds that political corruption tends to be greater in more religious countries. The study, published in the Review of Religious Research (online in July 2020), used data from multiple countries and from different time periods to determine whether religiosity is more important than religious affiliation in relation to corruption. Past studies have found that religious diversity and specific religious traditions might discourage corruption, but little has been done on the degrees of religious devotion in societies and their levels of corruption. Authors Omer Gokcekus and Tufan Ekici look at  the World Values Survey from 77 countries, focusing on different societies’ frequency of attendance and the importance of God and levels of corruption as measured by the International Country Risk Guide. The researchers find that more religious countries tend to have higher corruption levels even after taking religious affiliation into account and controlling for other variables. What these results say about how religion relates to corruption are unclear, they conclude. It may be that religion has an “opium effect,” blinding people to the corruption around them; or it may be that people become more religious in corrupt societies as they seek a refuge from such public behavior.

the World Values Survey from 77 countries, focusing on different societies’ frequency of attendance and the importance of God and levels of corruption as measured by the International Country Risk Guide. The researchers find that more religious countries tend to have higher corruption levels even after taking religious affiliation into account and controlling for other variables. What these results say about how religion relates to corruption are unclear, they conclude. It may be that religion has an “opium effect,” blinding people to the corruption around them; or it may be that people become more religious in corrupt societies as they seek a refuge from such public behavior.

(Review of Religious Research, https://www.springer.com/journal/13644)

![]() As a consequence of the stability of the Catholic population in the United Kingdom, contrasted with the decrease in proportion of Anglicans, “Britain will in a sense likely become a Catholic country once more in the coming years”, writes journalist Filip Mazurczak in The Catholic World Report (July 14, 2020). He hastens to add that a majority of society is likely to remain unchurched, but what may still happen is that the Roman Catholic Church could become the country’s largest religious body. In London, there are already more Roman Catholics than Anglicans. According to new research for the Christian thinktank Theos, summarized in The Guardian (June 24, 2020), “the biggest Christian denomination in London is Catholicism (35 percent of the Christian population), followed by Anglicanism (33 percent).” Pentecostals make up seven percent and Orthodox Christians six percent. Similar to what can be observed in some other areas of Europe with a previously majority Protestant population (e.g. cities such as Zurich or Geneva), in terms of percentage, the decline in religious affiliation is more pronounced among mainstream Protestants than among Roman Catholics.

As a consequence of the stability of the Catholic population in the United Kingdom, contrasted with the decrease in proportion of Anglicans, “Britain will in a sense likely become a Catholic country once more in the coming years”, writes journalist Filip Mazurczak in The Catholic World Report (July 14, 2020). He hastens to add that a majority of society is likely to remain unchurched, but what may still happen is that the Roman Catholic Church could become the country’s largest religious body. In London, there are already more Roman Catholics than Anglicans. According to new research for the Christian thinktank Theos, summarized in The Guardian (June 24, 2020), “the biggest Christian denomination in London is Catholicism (35 percent of the Christian population), followed by Anglicanism (33 percent).” Pentecostals make up seven percent and Orthodox Christians six percent. Similar to what can be observed in some other areas of Europe with a previously majority Protestant population (e.g. cities such as Zurich or Geneva), in terms of percentage, the decline in religious affiliation is more pronounced among mainstream Protestants than among Roman Catholics.

Moreover, immigration helps Roman Catholicism to compensate losses, something that is obvious to observers of attendance at Catholic Masses in Britain. This is caused not only by non-European immigrants, but also by people coming from Catholic areas of Central and Eastern Europe. According to results of the British Social Attitudes survey, published in 2018, the number of British people identifying with the Church of England more than halved between 2002 and 2017, falling from 31 percent to 14 percent, while those described as Roman Catholics have remained stable at around eight percent. As early as 2007, there were more Catholic than Anglican churchgoers in absolute numbers, Mazurczak reminds readers. Even if Anglicans continue to decrease and if Catholics might then become the largest religious body in Britain at some point in the future, this should not hide the fact that they represent less than a tenth of the total British population and that they would remain a minority in a country with a large percentage of unaffiliated people.

Moreover, immigration helps Roman Catholicism to compensate losses, something that is obvious to observers of attendance at Catholic Masses in Britain. This is caused not only by non-European immigrants, but also by people coming from Catholic areas of Central and Eastern Europe. According to results of the British Social Attitudes survey, published in 2018, the number of British people identifying with the Church of England more than halved between 2002 and 2017, falling from 31 percent to 14 percent, while those described as Roman Catholics have remained stable at around eight percent. As early as 2007, there were more Catholic than Anglican churchgoers in absolute numbers, Mazurczak reminds readers. Even if Anglicans continue to decrease and if Catholics might then become the largest religious body in Britain at some point in the future, this should not hide the fact that they represent less than a tenth of the total British population and that they would remain a minority in a country with a large percentage of unaffiliated people.

![]() New estimates of Anglicans in Africa suggest that Uganda rather than Nigeria is the center of African Anglicanism, writes Andrew McKinnon in the Journal of Anglican Studies (18). It has been widely held that Nigeria had the most Anglicans in Africa, with estimates of over 18 million believers, but on the basis of four nationally representative surveys, McKinnon writes that the

New estimates of Anglicans in Africa suggest that Uganda rather than Nigeria is the center of African Anglicanism, writes Andrew McKinnon in the Journal of Anglican Studies (18). It has been widely held that Nigeria had the most Anglicans in Africa, with estimates of over 18 million believers, but on the basis of four nationally representative surveys, McKinnon writes that the  proportion of Nigerians who identify as Anglicans “is much lower than is usually assumed (about four percent of Nigerians, or 7.6 millions persons in 2015).” While the church has grown, he adds that the evidence shows that the growth has been at the same pace as the population (not unimpressive considering the competition from Pentecostal churches). McKinnon finds that Anglicans in Uganda amount to about 27 percent of its population, though it is lower than estimated by the country’s Census. McKinnon concludes that the discrepancy between the Census and these representative surveys suggests that the proportion of Ugandans who identify as Anglican is in decline, “even if absolute numbers have been growing, driven by population growth.”

proportion of Nigerians who identify as Anglicans “is much lower than is usually assumed (about four percent of Nigerians, or 7.6 millions persons in 2015).” While the church has grown, he adds that the evidence shows that the growth has been at the same pace as the population (not unimpressive considering the competition from Pentecostal churches). McKinnon finds that Anglicans in Uganda amount to about 27 percent of its population, though it is lower than estimated by the country’s Census. McKinnon concludes that the discrepancy between the Census and these representative surveys suggests that the proportion of Ugandans who identify as Anglican is in decline, “even if absolute numbers have been growing, driven by population growth.”

(Journal of Anglican Studies, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-anglican-studies)