Eastern Orthodoxy is often said to be resistant to the cultural and theological battles that have marked other denominations, but the familiar scenario of conflict between “traditionalists” and “progressives” on matters of sexuality, gender, and politics is increasingly evident in this tradition. In the conservative ecumenical magazine Touchstone (May/June), Orthodox writer and priest Alexander F. C. Webster identifies an “Orthodox left” that is mounting a “Trojan horse” strategy seeking to effect change in these conservative churches. He charges that an Orthodox “elite” are dismissing more traditional believers as “fundamentalists”—a term that has been making the rounds in Orthodox theological conferences and journals and particularly propagated by prominent Fordham University theologian Aristotle Papanikolaou [see July 2016 RW]. Other theologians, such as Fordham’s George Demaopoulos and St. Vladimir’s Seminary’s Peter Bouteneff, as well as Archbishop Chrysostomous of Cyprus, have targeted such “fundamentalists” as being responsible for the lack of unity evident at last year Pan-Orthodox Council in Crete (several Orthodox bodies did not participate in the council for various reasons).

Webster cites Bouteneff’s report on the council in the mainline Protestant Christian Century magazine, where the latter concludes that Orthodoxy is “lagging in its responsiveness to modern demographic realities and to modernity in general,” as an example of this attitude. Webster’s article itself—and its publication in a well-known conservative magazine—suggests that both sides in these conflicts are positioning themselves in the two-party system of American religion marked by “liberals” and “conservatives.” While some Orthodox theologians have long been open to arguments about restoring women to the diaconate and even ordaining women to the priesthood, Webster sees support for such causes as stemming from Orthodox clergy and theologians’ increasing sympathy with gender and sexual liberation ideologies, leading up to “a soft-sell of the ancient proscriptions against abortions to the latest trend, ‘transgenderism.’” On LGBTQ issues, Webster sees a growing mood of tolerance and downplaying of church teaching on homosexuality among these elite theologians. But they are not far ahead of Orthodox laity; surveys have shown that American Orthodox laypeople are close to mainline Protestants and Catholics in their support of same-sex marriage (54 percent).

A new study suggests that the recent interest in bringing faith and spirituality to the workplace may be one factor behind rising rates of complaints about religious discrimination on the job. In the Review of Religious Research (March), Christopher Scheitle and Elaine Howard Ecklund note that the rate of reported complaints of workplace discrimination regarding religion has increased from 2.1 percent of all cases of workplace discrimination (1709 incidents) in 1997 to 4.0 percent (3721) in 2013, growing in both number and proportion. The issue of workplace discrimination against religion drew national controversy when the clothing retailer Abercrombie and Fitch was found liable in 2013 after it fired a Muslim employee for refusing to remove her head covering. Past research has found that specific religious identities, such as Muslim, as well as expressing religious identities, can increase the risk of workplace discrimination. But is religion discriminated against apart from specific religious identity and expression? The researchers used a survey of nearly 10,000 U.S. adults that draws on the GfK KnowledePanel, a nationally representative online panel of over 50,000 individuals and one of the few panels to ask a question about religious discrimination in the workplace.

Scheitle and Ecklund find that the frequency with which religion comes up in the workplace is positively associated with perceptions of religious discrimination. Just the presence of religion as a topic of conversation in the workplace “appears to present an independent risk of perceiving religious discrimination…moving from a workplace where religion never comes up to a workplace where religion often does almost triples the probability that an individual will perceive religious discrimination,” they write. The impact of such a dynamic on perceptions of discrimination is greater for mainline Protestants, Catholics, adherents of eastern religions (aside from Islam and Hinduism), those who are not religious, and atheists and agnostics.

Following last year’s visit of Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to Saudi Arabia, the Saudi Kingdom has agreed to finance the building of 560 “model mosques,” evoking mixed feelings among Muslim groups who do not share the Saudi Wahhabi interpretation of Islam. Dhaka Tribune (April 20) reports that these mosques will be equipped with libraries […]

While religious concepts and imagery remains off-limits in many contemporary art galleries, religious artifacts are beginning to find more of a reception in the world’s museums. In the Catholic magazine Commonweal (March 10), Daniel Grant writes, “Sincere expressions of spirituality or religious faith are largely absent from art galleries, except the ones that various churches and synagogues around the United States maintain or the museums of religiously affiliated colleges and universities. Instead, religion appears—when it does appear—as an object of scorn and suspicion.” Grant cites exhibitions at the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art, which included a painting by Mark Ryden showing a little girl in a Communion dress sawing into a piece of ham that bears the Latin inscription that translates into the “Mystical Body of Christ.” In 2015 the Milwaukee Art Museum acquired the controversial portrait by Niki Johnson of Pope Benedict XVI, “Eggs Benedict,” which was created with 17,000 multi-colored condoms. Grant traces much of the disdain and dismissal of religion to the art school and Master of Fine Arts programs, where students are actively discouraged from creating work that addresses spirituality, ritual, and faith, especially if it concerns Christianity. Art historian and critic James Elkins says that student artists are trained to concentrate on “criticality in relation to existing power structures,” be they received ideas, capitalism, or the church.

While much contemporary art focuses on identity, such as race, gender, and sexual orientation, and religion is one element of identity, those other identity markers are more fluid and open to interpretation, whereas religion is “more set in time and less open to reconsideration, certainly less tolerant of difference,” Grant writes. By the time these artists reach the commercial art world, “they know to keep their beliefs quiet or face rejection.” Grant concludes, “What does seem unnerving is the fear that many art-gallery and museum directors have about offending visitors, even when many of those museum officials bravely defend—on grounds of free expression—artwork that might force parents to cover their young children’s eyes.” The new book Religion in Museums (Bloomsbury, $26.96), edited by Gretchen Buggein, Crispin Paine, and S. Brent Plate, makes a similar critique, though some of the contributors see signs of greater openness to religious themes surrounding art and artifacts. In the Foreword, Sally Promey of Yale University notes that the new interest in religion “roughly coincides with the dismantling of secularization theory,” which had led museums to see religion as a “vestigial organ or appendage, a relic of the past, or a token of presumably less advanced civilizations. …That Sister Corita Kent can be resurrected in 2015–16 as a Pop artist, with art historians paying scant attention, beyond the merely descriptive, to the substance of her religious convictions and practice, however, provides a recent example that demonstrates how tough it is to shake fundamental ingrained cultural hierarchies and biases.”

The Christian Century (February 15) reports that mainline seminaries are increasingly partnering with megachurches for financial reasons as well as to draw on their expertise in evangelism, church growth, and leadership. Residential-based seminary education, with its high tuitions and other living expenses, has increasingly been falling out of favor with seminarians and potential clergy, who are opting for online and distance learning programs that they complete without leaving their homes and careers. Mainline seminaries’ continuing financial problems due to low enrollment and the resulting difficulties in maintaining old buildings are other factors that have moved megachurches into the theological education field. Those seminaries that have shown some resilience are the ones that have teamed up with larger churches to deliver their educational services, writes Jason Byassee and Ross Lockhart. Saint Paul’s School of Theology in Kansas City was forced to close its campus in the center of the city and start holding its classes in the 20,000-member Church of the Resurrection in the suburbs.

This United Methodist megachurch provides the school with practicums that offer “nuts-and-bolts topics like funerals, stewardship, and youth ministry.” There is some tension in the fact that Saint Paul’s is more liberal in theology and oriented more toward social action than the centrist evangelical megachurch. Asbury Theological Seminary in Kentucky is another example of this trend, though in this case the unaffiliated (and more evangelical) school in the Wesleyan tradition has “planted” a satellite seminary in another United Methodist megachurch in Memphis, Tennessee. The new campus makes little effort to offer on-campus formation, instead drawing on the congregation’s extensive ministry in downtown Memphis. St. Mellitus College has pioneered a similar kind of partnership in the U.K. The seminary, with about 400 students, was the result of a merger between two diocesan theological programs associated with the evangelical “megaparish” Holy Trinity in Brompton and St. Jude’s Church in the west of London.

Buddhism in the West continues to see the rise of new figures and movements, though not all are acknowledging their Buddhist roots, according to a roundtable discussion of scholars and practitioners in the Fall issue of French magazine Ultreïa!. Some of these assessments differed between France and America. Philipe Cornu, an academic and a teacher of Buddhism, notes how successful mindfulness has become in various circles while often rejecting its Buddhist roots. While some might see this popularity as a proof of Buddhism’s success in the West, Cornu is not so sure. Appropriating elements of Buddhism while ignoring that they are part of a wider spiritual path shows how many often do not take Buddhism as a whole but rather reduce it to small pieces, such as techniques for well-being and advice for daily life. The potential for narcissism in this approach is a far echo from the Buddhist message as a path to liberation from conditioned existence, associated with compassion and altruism, Cornu adds. The original medical applications of mindfulness in the late 1970s were a way of using Buddhist techniques to help patients, while more recent uses rather tend to stress efficiency in one’s professional life. Benefits are obvious, but a pinch of spirituality in daily life cannot be equated with a spiritual path. Such uses of Buddhism in the West make it difficult at this point to foresee what its future could be, Cornu concludes.

A teacher of Zen, Eric Rommeluère, is aware that Zen Buddhism has mutated through its history and has been influenced by different environments and historical events. The propagation of Zen Buddhism in the West is largely the consequence of a decision by monks to relieve themselves of their priestly duties in Japanese society and diaspora for the sake of teaching international audiences. Initially, Zen attracted people who had been influenced by the views of the counterculture. These days, Rommeluère adds, this association is no longer the case, to the extent that Zen Buddhism has sometimes become diluted into mainstream culture. As with other Buddhist schools, the success of mindfulness techniques presents a challenge. Fewer people are willing to commit themselves for retreats lasting for several months, and seminars of a short duration are preferred. In France, at least, Rommeluère is not so sure about the future of Buddhism—especially Zen— as the competition from mindfulness challenges it.

The Chinese curse of “living in interesting times” took on special resonance in 2016 as political upheavals and conflicts as well as actual violence became a reality for many. These tumultuous events reverberated in the world of religion, as will be obvious by our focus on religion and politics for our annual review of 2016 and preview of trends unfolding in 2017. Citations of RW issues where we cover the trends below in greater depth follow each item; we also cite outside sources for trends reported for the first time here.

1) The election of Donald Trump will have numerous implications for religion, some of which are only in their infancy. Despite the abrasive and divisive campaign Trump ran and the way that it divided Republicans, subsequent polls have shown that the religious configurations marking the electorate for the last two decades have not changed much. It is not clear if evangelicals’ and other religious conservatives’ investment in the Trump presidency—with notable dissenters—will revive the religious right and its agenda (see “The religious right’s populist turn,” below), but their worries about secularism and the loss of institutional religious commitment among many Americans will not likely subside even with political support from Washington. Their association with a controversial and potentially unpopular administration may well exacerbate the situation (December RW).

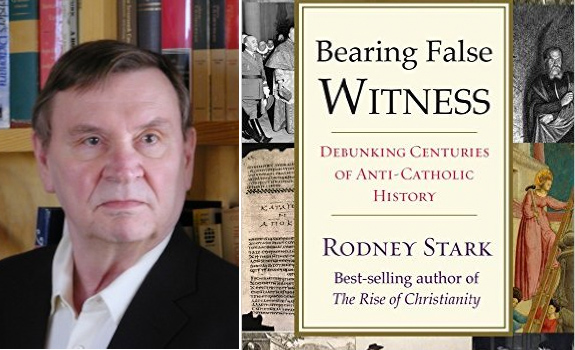

For a change, RW turns to historical trends in religion, namely the phenomenon of anti-Catholicism as documented by Baylor ISR’s co-director Rodney Stark in his new book Bearing False Witness (Templeton Press, $19.57). The book covers topics ranging from myths about Catholic origins and the “lost” Gospels to Catholicism’s attitudes concerning slavery, science, and capitalism. We briefly interviewed Stark about his book in early December.

RW: There have been other books on anti-Catholicism, but Catholics have usually written them; as a non-Catholic, what interested you enough about this subject to write a book on it?

Stark: I kept running into these dreadful lies, and they not only prompt anti-Catholicism, they badly distort history. I became concerned that so many of them are taken for granted by educated people.

RW: The book sets out to debunk stereotypes and other popular myths about Catholicism throughout history, such as about the church’s role in the Inquisition and the Crusades. What myth did you uncover that was the most surprising to you during your research?

Stark: Until I was faced with overwhelming data, it was inconceivable to me that the Inquisition was other than a dreadful, murderous institution. That it was, in fact, a force for moderation was inconceivable to me. But, the fact that the witch-hunts that swept through the rest of Europe were prevented in Italy and Spain by the Inquisition is undeniable. And that was only one of its good deeds.

RW: The role of the church in World War II and its complicity or at least passivity in the face of persecution of Jewish people has been the subject of several popular books, but you argue that the church was unfairly attacked on this front; can you explain that?

Stark: The overwhelming testimony by major Jewish figures is that the church opposed Hitler and managed to save a lot of Italian Jews. The lie about Hitler’s pope began in Moscow.

There is much talk about the growth of “Christian nationalism” even as surveys and journalists report the decline of “white Christian America,” but several papers presented at the late October meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in Atlanta suggest that any such phenomenon is far from a monolithic or accelerating force in society. Sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Christopher Scheitle presented a paper showing that while Christian nationalism, which they define as a position linking the importance of being Christian to being American, had shown growth between 1996 and 2004, the subsequent period up to 2014 had seen decline in this ideology. Using data from the General Social Survey in 1996, 2004, and 2014, the researchers found that 30 percent of Americans held this position in 1996, while 48 percent did in 2004, but then the rate dropped back to 33 percent in 2014. They looked at other variables that seek to maintain boundaries for true Americans, such as the importance of speaking English, and did find that this sentiment followed the same episodic pattern. Whitehead and Scheitle argue that the role of patriotism and attachment to America was stronger in 2004, which was closer to 9/11, than in the earlier and later periods. Although they didn’t have data for the last two years, they speculated that these rates may be increasing again.

Female atheists and secular humanists can be considered a minority of a minority—atheists representing a small proportion of the U.S. population and women comprising a small proportion of that number—but they have been reaching higher levels of involvement and leadership in secularist organizations in recent years. At the Women in Secularism conference meeting in Washington in late September, attended by RW, several speakers confirmed that women are more involved in organized atheist and secular humanist activism and communities even while there are still divisions over the role of feminism in the wider movement. This event was the fourth such conference, with its origin in 2010 over the concern that more strident voices of new atheists, who were viewed as demeaning women (and even having a role in cases of alleged sexual harassment at atheist events), were drowning out women’s issues. The clash between the more science-oriented new atheists and activist and social justice-oriented secularists was evident at the conference. Organizer Debbie Goddard told RW in an interview that the recent merger of the Center for Inquiry, the sponsor of the Women in Secularism conferences, and the new atheist-oriented Richard Dawkins Foundation has been a source of dissension among women in the movement, likely causing the recent gathering’s registration to hit a low of 80 participants. Past conferences put more stress on social activism, and several of the earlier activist and feminist leaders did not attend the event, Goddard added.

But other speakers reported on the new openness of women to atheism as the movement tries to draw on the swelling numbers of non-affiliated Americans. Melanie Brewster of Columbia University presented a paper on why men are more likely to be atheists than women. Prominent new atheist leaders such as Sam Harris have made controversial statements that the cerebral nature of atheism attracts men more than women, who are more “nurturing.” Brewster argued that whatever the reasons for the gap between male and female secularists (and religiosity), the differences are narrowing, especially in Western nations. She added that women may be experiencing a “time-lag” in secularization and only today are showing the drop off in religiosity. Another study she cited showed that women feel excluded from the atheist movement and need to see greater representation of atheist women in the media.