Photo of Southern Evangelical Seminary.

A recent survey finds that the top 10 seminaries in terms of enrollment do not include a single mainline seminary and tilt decidedly toward the evangelical and, in particular, Baptist side of the spectrum. The Aquila newsletter (December 1) cites an analysis by Nathan McKanna of data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), finding that of the 245 accredited seminaries, evangelicals now outnumber mainline Protestants 46 percent to 33 percent. And of that 33 percent of Protestants, females outnumber males two to one. Of the 10 seminaries with the largest enrollment now, 80 percent are Baptistic if not formally Baptist; for instance, Dallas Seminary is officially independent but is doctrinally close to the Baptists. The only two non-Baptistic seminaries in the top 10 are Fuller and Asbury (Methodist). Adding together Dallas, Gateway, and Liberty (with sharp gains in enrollment, though a large part of it is online), along with the other schools with “Baptist” in their name, makes for a total of 13,826 full-time students. This now represents a ratio of 15 to 1 of Baptists over Methodists, with little other representation from mainliners—“a sea change in American theological education.”

Many of the largest seminaries have reduced the number of hours to receive a standard divinity degree, and the classical emphasis on biblical languages has been shortened in most seminaries. Another far-reaching development is the rapid increase in online studies, with approximately 70 percent of classes taking place online compared to 30 percent 10 years ago. The study concludes by noting that “The average headcount at seminaries in the United States is 303 students, but what’s interesting is that more than 75 percent of seminaries (191) have an enrollment below that figure. … In other words, nearly half of all student enrollment is concentrated in just 7 percent of seminaries, all of which are evangelical Protestant.”

(The analysis can be downloaded at: https://www.logos.com/grow/hall-top-seminaries-by-enrollment/)

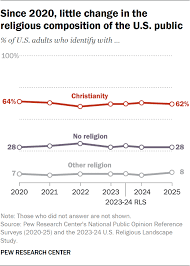

The main indicators of American religious devotion continue to stabilize after a long period of decline, according to a Pew Research Center survey. The shares of U.S. adults who identify with Christianity, with another religion, or with no religion have all remained fairly stable in the center’s latest polling, a pattern that started five years ago. The percentages of Americans who say they pray every day, that religion is very important in their lives, and that they regularly attend religious services also have held fairly steady since 2020. While some observers have reported that a religious revival is serving to stabilize the numbers of non-affiliated, the Pew researchers argue that there are no clear signs of nationwide revival, though they allow that there may be local religious upsurges. The finding that young men are now about as religious as women in the same age group represents a “notable change from the past, when young women tended to be more religious than young men. It also differs from the pattern seen among older people. This narrowing of the gender gap is driven by declining religiousness among American women. It is not a result of increases in the religiousness of men.”

(To download this report, visit: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2025/12/08/religion-holds-steady-in-america/)

In middle-income rural communities in the country’s upper tier and interior West, called “Rural Middle America” and “LDS Enclaves,” 59 percent of residents said religion and faith were important in American life, while in the “African American South” and “Military Posts,” known for their large Black populations, 57 percent and 52 percent of residents said so, respectively. On the other side of the spectrum were such urban-oriented places as “Big Cities,” “Urban Suburbs,” and “College Towns,” which registered in the mid- to upper-40s. Beyond these divides, attending religious services was not found to be widely popular. Across communities, only 4 in 10 said they attended religious services at least every few months. “Graying America” counties, where more than a quarter of residents are 65 and older, were the exception, with 51 percent saying they never attended services. Regarding religious identity, 56 percent of all those considering themselves Protestant, other Christians, or other non-Christians identified as evangelical or born-again. There was no definite urban-rural split, with percentages reaching the mid- to upper-60s in the African American South, Working Class Country, and Evangelical Hubs. But even the big cities mirrored the national average, while Urban Suburbs and Aging Farmlands were both in the mid-40s.

(The ACP/IPSOS survey can be downloaded from: https://www.americancommunities.org/americans-identify-with-religious-diversity-but-they-divide-over-religions-role/)

The larger churches in the study were more open to organizational change, largely because they could hire and retain qualified staff. Smaller churches were more likely to struggle in this area, making quality programming more of a challenge. On external challenges, larger and smaller churches faced different perceptions of risk. A loss of a few members in smaller churches could make them more likely to face financial collapse. Similarly, in smaller churches, members’ exposure to opposing beliefs, such as atheism, could have more serious results than in larger churches. The latter have larger social networks that can help members deal with such challenges to belief, whereas smaller churches have fewer such resources, making them more vulnerable.

(Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, https://www.religjournal.com/articles/article_view.php?id=192)

An analysis of 28 countries in the European Union finds that the separation of religion and state is rarely practiced, and that even countries that may qualify as secular meet only loose standards of secularism and neutrality regarding religion. The study, published in the journal Politics and Religion (online in November) and conducted by Jonathan Fox of Bar Ilan University in Israel, is based on the Religion and State dataset. It looks at five different variables to measure the separation of religion and state (SRAS): government-based religious discrimination; restrictions, regulations, and control of the majority religion; government religious support; whether governments finance religion; and whether the state declares an official religion. Fox finds that none of the 28 countries practice SRAS as it is expressed in such policies as zero tolerance (where if a state bans an action, it must meet this standard with no exceptions), while some of the EU states might strictly uphold neutrality on religion (such as the Netherlands and Slovenia). The researcher concludes that SRAS is either uncommon or non-existent in the EU. But he also adds that there is a deficit of religious freedom in these countries, all of which “restricted the religious practices and/or institutions of religious minorities in a manner that that was not applied to the majority religion…”

(Politics and Religion, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-religion)

Across the majority of faiths, conversion is linked to greater purpose and wellbeing. The report argues that religion is increasingly functioning as an “existential toolkit” for healing and purpose rather than a set of communal obligations—although one should not underestimate the appeal of structured, embodied practices, for instance, in conversions to Islam. Deep transformations are underway, with the story being “no longer one of simple decline but of diversification, from organized religion toward personalized meaning systems that combine elements of faith, spirituality, and moral individualism.”

(Institute for the Impact of Faith in Life, https://iifl.org.uk)

The demographic profile of regular churchgoers shows an average age of just under 50, with nearly one-third living in the Paris region—evidence of an increasingly urban Catholicism. Slightly more than half are men. Crucially, nearly two-thirds come from families that regularly attended mass, underscoring the importance of family transmission, though 13 percent follow a form of renewal Catholicism and come from non-practicing backgrounds. Politically, 40 percent of the regular churchgoers identify with the right or far-right (15 percent with the Rassemblement National/National Rally), 30 percent with the left or far-left, and 15 percent with the presidential majority. Political scientist Yann Raison du Cleuziou says the survey shows that French Catholicism is reorganizing around a “hard core” of 3 million regular churchgoers who are highly committed and mutually reinforce each other. The increase in adult baptisms does not compensate for the collapse in infant baptisms.

The apparent dynamism of certain downtown parishes serves as a “magnifying glass effect,” with zealous Catholics, once dispersed, now concentrated in a few locations, creating an impression of renewal. Those who value religious obligation have resisted detachment better than those who prioritized personal fulfillment. Remaining practitioners therefore tend to be more conservative. Although they are not all attracted to it, two-thirds of regular Catholics no longer object to the Latin Mass, which has moved beyond post-Vatican II conflicts. Only 22 percent of regular churchgoers consider it a step backward. It now serves as a spiritual resource for young people, a “pole of intensity” that anchors faith. While no more than 9 percent say the Latin Mass is their preferred form, 25 percent of the regular churchgoers report liking both forms equally. According to an article by Matthieu Lasserre and Eve Guyot (La Croix, December 11), there is a growing phenomenon of “bi-ritualism” among practicing French Catholics, where faithful attend both the traditional Latin Mass (Tridentine rite) and the ordinary form. These Catholics are predominantly young adults under 35, living in large cities where they have access to both forms.