But Schlumpf adds that the increasing percentage of Catholic women opting for Trump between 2016 and 2024 may indicate that some women were slower to accept or ignore Trump’s negatives. Mary FioRito of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, DC, says that working-class white Catholic men were quicker to respond to Trump because he tapped into their feelings of being disrespected by elites. Trump’s choice of Catholic convert JD Vance as his running mate and the assassination attempt on him in July 2024 may also have brought around some Catholic women voters, according to FioRito. Abortion is cited as an issue that could have attracted Catholic women to the GOP and to Trump, although the overturning of Roe v. Wade gave other issues, such as immigration and the economy, more priority in 2024. The Democratic Party’s move to the left on issues like transgender rights could also have turned women toward Trump. And another possible reason for the turn to Trump among Catholic women is that progressive Catholic women may have been leaving the church in reaction to conservative politics. “If progressive Catholic women leave,” Schlumpf notes, “the remaining Catholic women are more likely to be conservative—thus the higher percentage of GOP voters.”

(Commonweal, https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/)

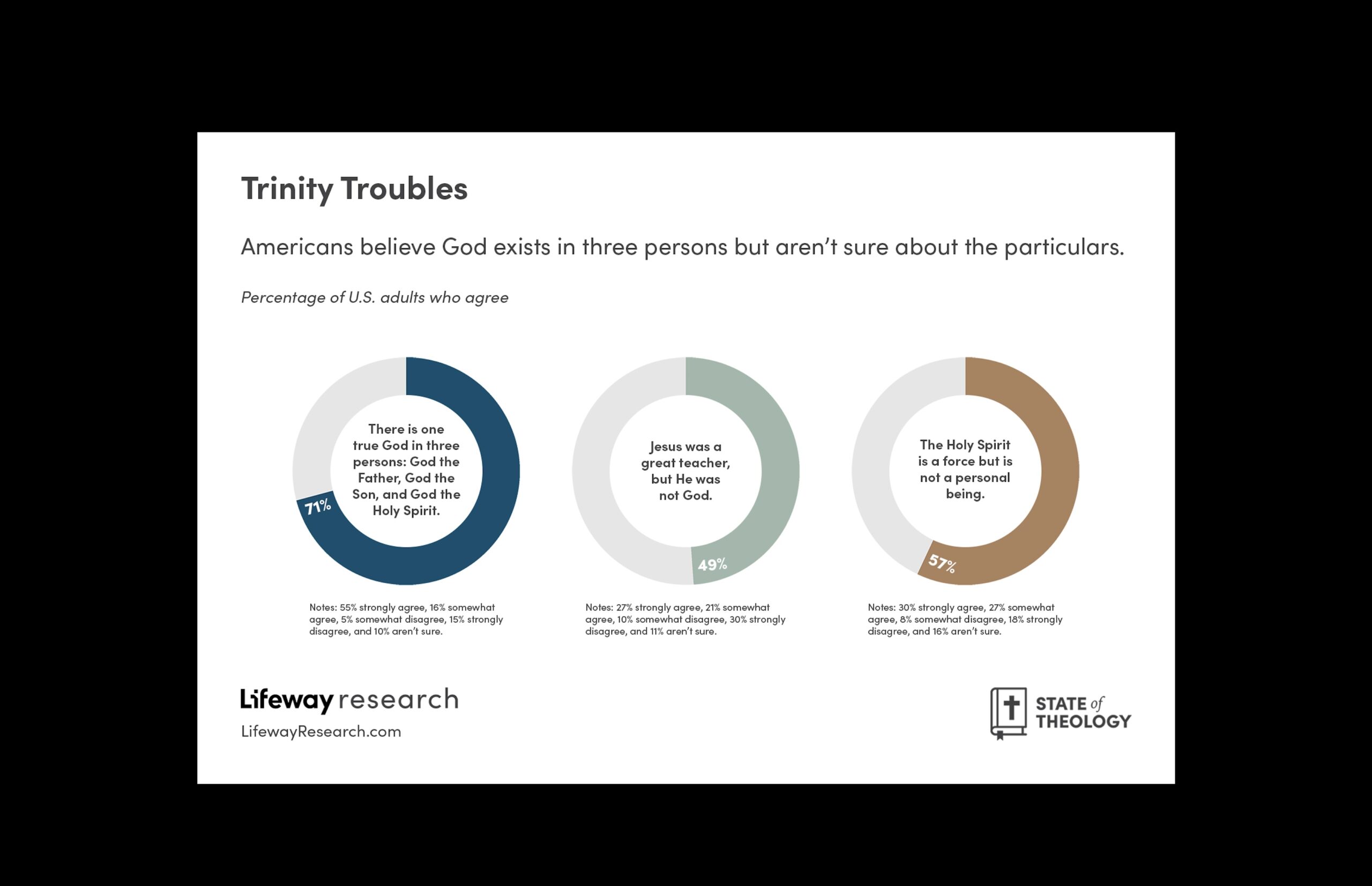

As for different belief systems, it was found that U.S. adults feel some conflict about the validity of these faiths. About two in three (65 percent) said God accepts the worship of all religions, including Christianity, Judaism and Islam; 46 percent agreed religious belief is not about objective truth, while a third (32 percent) disagreed. As far as practice, one significant change since the pandemic has been on the validity of worshipping alone or with one’s family. In 2022, following the pandemic, 66 percent of Americans said such private worship is a valid replacement for regularly attending church. The two-thirds who agreed marked a significant increase from 58 percent in 2020. This year, the percentage has dropped but remains above pre-pandemic levels at 63 percent.

(The complete report can be downloaded from: TheStateOfTheology.com and LifewayResearch.com/StateOfTheology)

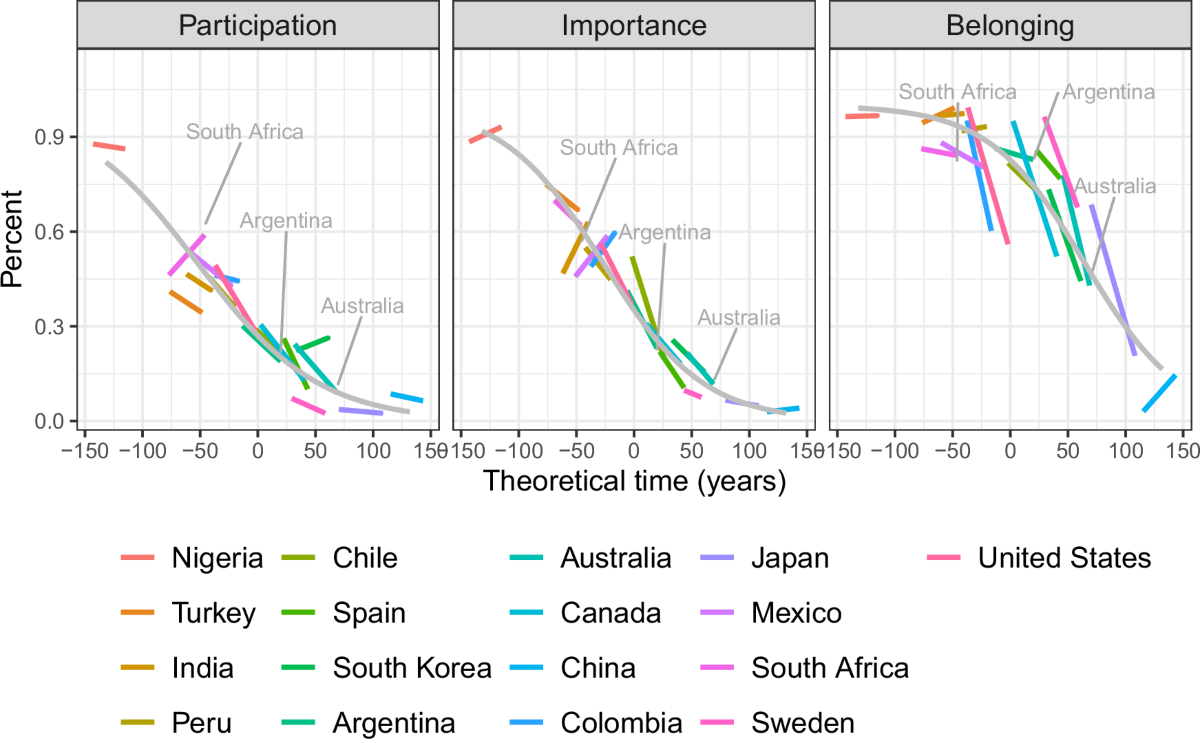

Stolz, de Graaf, Hackett, and Antonietti argue that over a period of 200 years, most countries will follow this sequence of religious decline, with successive generations shedding more demanding traits of religion first, and less costly traits later. Europeans are the furthest along this proposed secular trajectory, while the highly religious countries are just starting the first stage. Countries in the Americas, Asia, and Oceania are in the middle stage of this global “secular transition,” according to the researchers. The one exception to this pattern is the post-Soviet Eastern European countries and Russia, Georgia, Belarus, and Moldova, which do not show the expected cohort differences. Much of the Muslim world is categorized under Asia, but a recent article in the journal Religion, State, and Society (online in September) questions whether the Middle East and North Africa are actually following the secularization pathway. Esen Kirdis (Rhodes College) acknowledges the sharp growth of non-believers in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), but finds that personal piety remains strong.

Kirdis notes that there are some differences in the data on the extent of the growth of non-belief in this region, with the Arab Barometer (AB) survey showing less religious decline than the World Values Survey (WVS). For instance, the Arab Barometer shows more respondents being “somewhat religious” than the WVS (even showing a spike and then a decline in the number of non-believers in Morocco, Egypt, and Jordan). The difference may be due to the fact that the AB allows for this “somewhat religious” category, while the WVS questionnaire items follow more of a religious and secular binary. The AB also finds that for 99.2 percent of respondents, religion is “very” or “rather” important. The WVS also finds that religious belief and practices remain high, with even the majority of the “non-religious” saying they pray regularly (70 percent). Kirdis finds that while religious self-identification is indeed decreasing, belief and practices remain high in the region. She argues that it is declining trust in Islamic institutions and in political Islam, which is closely linked with religious self-identification in the MENA, that is mainly responsible for the growth of the region’s “non-believers,” who nevertheless do in fact believe.

(Nature Communications, https://www.nature.com/ncomms; Religion, State, and Society, https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/crss20)

Suzin looked at the three major ultra-Orthodox communities in Israel: the Lithuanian community, the Hasidic Jews, and the Sephardic Mizrahi community. He found that it was the Lithuanian community that was the “most significant factor in the emergence of social activism in ultra-Orthodox society,” with the most social activity within civil society organizations coming mainly from members of this community. The Lithuanian community’s commitment to Torah study, viewing itself as a “society of learners,” has fueled the growth of the ultra-Orthodox feminist movement and other social initiatives. Suzin adds that the Hasidic community has a more rigid hierarchical leadership that teaches that holiness is based on obeying the Rebbe and community rules rather than on self-learning and providing solutions for individual needs, as the Lithuanians believe. The strongly ethnic Mizrahi ultra-Orthodox, while close in structure to the Lithuanians, are more isolationist in relation to the wider Israeli society, likely leading to less social involvement.

(Journal of Jewish Identities, https://muse.jhu.edu/journal/463)