After controlling for demographic factors such as age, race and gender, frequent spiritual practitioners were about 30 percent more likely than nonpractitioners to report engaging in at least one political activity in the past year. Similarly, devoted religious practitioners were also about 30 percent more likely to report one of these political behaviors than respondents who did not practice religion. “In other words, we found heightened political engagement among both the religious and spiritual, compared with other people. The spiritual practitioners we identified seemed particularly likely to be disaffected by the rightward turn in some congregations in recent years. On average, Democrats, women and people who identified as lesbian, gay and bisexual reported more frequent spiritual practices.”(The Conversation, https://religionnews.com/2022/09/03/yoga-versus-democracy-what-survey-data-says-about-spiritual-americans-political-behavior/)

After controlling for demographic factors such as age, race and gender, frequent spiritual practitioners were about 30 percent more likely than nonpractitioners to report engaging in at least one political activity in the past year. Similarly, devoted religious practitioners were also about 30 percent more likely to report one of these political behaviors than respondents who did not practice religion. “In other words, we found heightened political engagement among both the religious and spiritual, compared with other people. The spiritual practitioners we identified seemed particularly likely to be disaffected by the rightward turn in some congregations in recent years. On average, Democrats, women and people who identified as lesbian, gay and bisexual reported more frequent spiritual practices.”(The Conversation, https://religionnews.com/2022/09/03/yoga-versus-democracy-what-survey-data-says-about-spiritual-americans-political-behavior/)

Source: iStock – SDA Church.

They were surprised by the fact that while the heaviest shoppers were non-denominational Christians, there was a low rate of switching to other congregations among this group. Politics also did not play a significant role in congregational shopping, though it did motivate a segment of members to leave their congregations during the pandemic. Even if congregational shopping does not lead to high rates of members leaving their congregations, if the practice is continued, it may have other effects. Higgins and Djupe write that congregational shopping could “intensify the pressure on congregations to attract and retain attenders in part because they know people are shopping, while they do not know their likelihood of leaving.” The practice could promote standardization of services, especially in the same community. “If political engagement, for instance, is becoming more common among evangelicals, ease of accessing other congregations could encourage the diffusion of that norm,” they conclude.

(Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14685906)

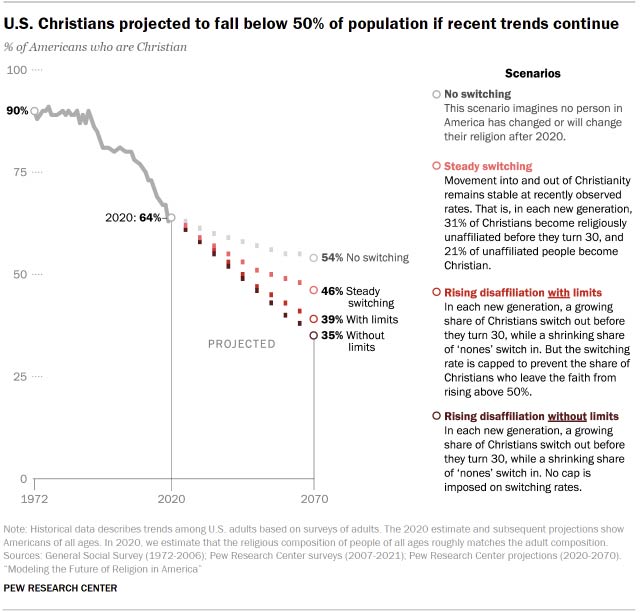

By contrast, a second scenario of rising disaffiliation without limits assumes an ever-increasing momentum behind religious switching. The rise of the unaffiliated might induce increasing numbers of young people to leave Christianity and “further increase the ‘stickiness’ of an unaffiliated upbringing, so that fewer and fewer people raised without a religion would take on a religious identity at a later point in their lives.” But continued religious socialization of children may make them less likely to disaffiliate, continuing a “self-perpetuating core of committed Christians who retain their religion and raise new generations of Christians.” The “rising disaffiliation with limits” scenario best illustrates what would happen if recent generational trends in the U.S. continue, “but only until they reach the boundary of what has been observed around the world, including in Western Europe.” This scenario reflects the patterns observed in recent years. “These projections indicate the U.S. might be following the path taken over the last 50 years by many countries in Western Europe that had overwhelming Christian majorities in the middle of the 20th century and no longer do. In Great Britain, for example, ‘nones’ surpassed Christians to become the largest group in 2009, according to the British Social Attitudes Survey. In the Netherlands, disaffiliation accelerated in the 1970s, and 47 percent of adults now say they are Christian,” the report concludes.(The Pew report can be downloaded from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/09/13/ modeling-the-future-of-religion-in-america/)

By contrast, a second scenario of rising disaffiliation without limits assumes an ever-increasing momentum behind religious switching. The rise of the unaffiliated might induce increasing numbers of young people to leave Christianity and “further increase the ‘stickiness’ of an unaffiliated upbringing, so that fewer and fewer people raised without a religion would take on a religious identity at a later point in their lives.” But continued religious socialization of children may make them less likely to disaffiliate, continuing a “self-perpetuating core of committed Christians who retain their religion and raise new generations of Christians.” The “rising disaffiliation with limits” scenario best illustrates what would happen if recent generational trends in the U.S. continue, “but only until they reach the boundary of what has been observed around the world, including in Western Europe.” This scenario reflects the patterns observed in recent years. “These projections indicate the U.S. might be following the path taken over the last 50 years by many countries in Western Europe that had overwhelming Christian majorities in the middle of the 20th century and no longer do. In Great Britain, for example, ‘nones’ surpassed Christians to become the largest group in 2009, according to the British Social Attitudes Survey. In the Netherlands, disaffiliation accelerated in the 1970s, and 47 percent of adults now say they are Christian,” the report concludes.(The Pew report can be downloaded from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/09/13/ modeling-the-future-of-religion-in-america/)

Source: Combating Terrorism Center.

Source: The Hank Center for the Catholic Intellectual Heritage.

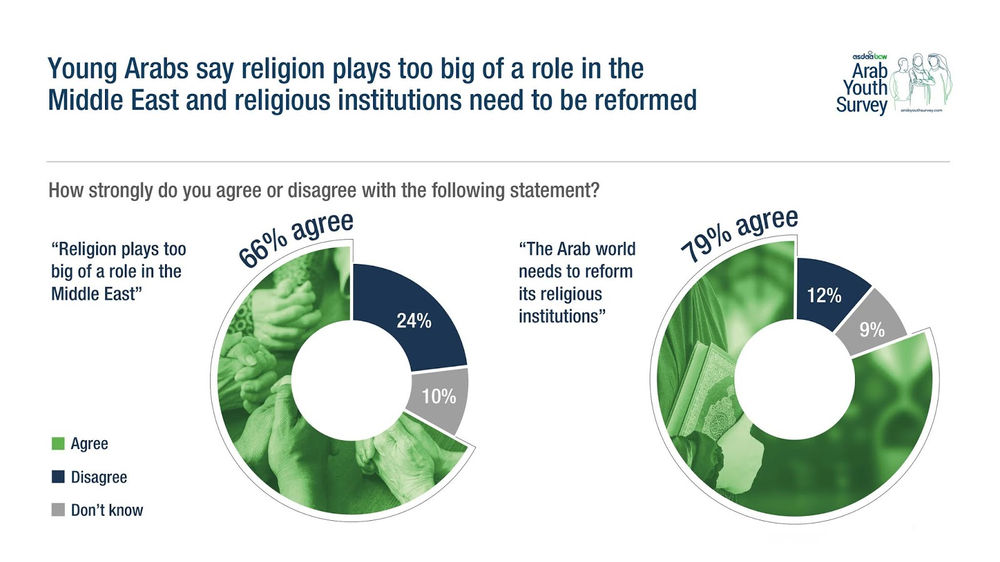

In some cases, answers reflect similar percentages from one area to another, but there are also significant regional variations. Fifty-four percent of youth in North Africa and 45 percent in the Gulf states claim religion as the most important part of their identity, but the percentage is down to 24 percent in the Levant. Despite widespread feelings that religion plays too big a role in the Middle East, 70 percent in the Gulf, 60 percent in North Africa, and 41 percent in the Levant say the laws in their country should be based on sharia. A majority (up to 91 percent in Algeria) claim to be concerned about the loss of traditional values and culture, and stress that it is important for them to preserve their religious and cultural identity, even if it means giving up a globalized and more tolerant society; but the proportion goes down to 34 percent in Yemen and 23 percent in Syria, two war-torn countries. In-depth country-specific surveys and field research are required in order to understand what the trends among Arab youths mean in relation to religion, its public role, and the place of religious institutions. Indeed, as the history of contemporary Islam shows, the desire for “reform” can have different practical meanings.(James M. Dorsey’s informative column, The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer, has been published for 12 years and can be accessed for free or be supported by becoming a paid subscriber: https://jamesmdorsey.substack.com; Arab Youth Survey – https://arabyouthsurvey.com/en/findings/)

In some cases, answers reflect similar percentages from one area to another, but there are also significant regional variations. Fifty-four percent of youth in North Africa and 45 percent in the Gulf states claim religion as the most important part of their identity, but the percentage is down to 24 percent in the Levant. Despite widespread feelings that religion plays too big a role in the Middle East, 70 percent in the Gulf, 60 percent in North Africa, and 41 percent in the Levant say the laws in their country should be based on sharia. A majority (up to 91 percent in Algeria) claim to be concerned about the loss of traditional values and culture, and stress that it is important for them to preserve their religious and cultural identity, even if it means giving up a globalized and more tolerant society; but the proportion goes down to 34 percent in Yemen and 23 percent in Syria, two war-torn countries. In-depth country-specific surveys and field research are required in order to understand what the trends among Arab youths mean in relation to religion, its public role, and the place of religious institutions. Indeed, as the history of contemporary Islam shows, the desire for “reform” can have different practical meanings.(James M. Dorsey’s informative column, The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer, has been published for 12 years and can be accessed for free or be supported by becoming a paid subscriber: https://jamesmdorsey.substack.com; Arab Youth Survey – https://arabyouthsurvey.com/en/findings/)

The growth of Islamic stamps of approval for products and services has been encouraged by government policies implemented in Malaysia and Indonesia to promote sectors such as halal food and Islamic banking as economic drivers, as well by political parties who have “helped bring religious observance, once personal and private, into the public sphere” in their search for Muslim votes. Urbanization is also said to have played a key role, since those who left villages have been looking “for a network they can trust.” But there are also voices decrying a “commercialization of religion.” And the report warns that “the definition of halal is

The growth of Islamic stamps of approval for products and services has been encouraged by government policies implemented in Malaysia and Indonesia to promote sectors such as halal food and Islamic banking as economic drivers, as well by political parties who have “helped bring religious observance, once personal and private, into the public sphere” in their search for Muslim votes. Urbanization is also said to have played a key role, since those who left villages have been looking “for a network they can trust.” But there are also voices decrying a “commercialization of religion.” And the report warns that “the definition of halal is