While new religious movements (NRMs) tend to be seen by church and state authorities as a threat to “spiritual security” in the Russian Federation, they seem mostly to be perceived as a minor and relatively innocuous phenomenon in other post-Soviet countries if one reads the articles on various NRMs in Russia, Ukraine, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia, and the Czech Republic published in Religion & Gesellschaft in Ost und West (Feb.). There are indications that the Russian Orthodox Church has been intensifying its work against NRMs in recent times. In December there was also a round table at Russia’s Parliament on “sects and destructive cults” as challenges to Russia’s security. Participants—including both academics and representatives of church and state—discussed if there might be a need for specific legal measures against “destructive cults.”

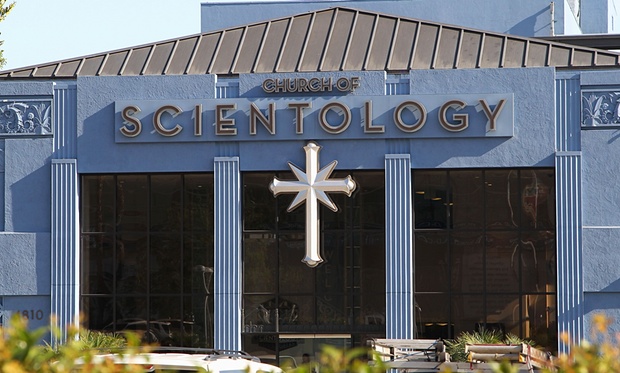

There is indeed a lively NRM scene in Russia writes Marat Shterin (King’s College London), although the number of their followers remains rather stable. Beside international NRMs (Scientology continues to be successful, Unification Church has declined), this group includes dozens of Russian-born NRMs with a regional or national presence, a few of them even with followings outside of Russia. After a liberal period after the end of the Soviet Union, the new legal framework in force since 1997 gives a privileged position to “traditional religions” (although this expression is not used). Since 2000, the national security concept envisions foreign missionary activities as a potential threat. Cooperation between state organs and the Orthodox Church has also developed in that area. Even legally recognized groups such as Jehovah’s Witnesses experience police harassment or local limitations to their activities. While some major (international) groups have successfully protested to the European Court of Human Rights, not all NRMs are able to pursue such paths due to lack of human resources and legal knowledge. Thus while NRMs continue to attract Russian followers, their future to a large extent depends upon political and social developments within the country writes Shterin.

In Latvia, according to Milda Ališauskiené (Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas), there has been no lack of controversies around NRMS, including anti-cult groups (no longer active since the mid-2000s), and public opinion remains rather negative in general, although a trend toward a more neutral attitude is observed. But media reports tend to be sensational and to rely primarily on Roman Catholic priests and theologians as resource persons on the topic; the media have largely contributed to creating stereotypes about NRMs, Ališauskiené adds. In Poland, the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church still plays a role in NRM matters. While Paweł Załęcki (Copernic University, Toruń) estimates that there are more than 300 NRMs in the country, most of them are not growing or are declining. There is little indication that this trend might change in the coming years. Załęcki emphasizes that renewal movements within the Roman Catholic Church, with new forms of religious expression compared to mainstream Catholicism, represent a significant phenomenon, on the other hand: for instance, the Light-Life Movement (Oasis Movement). In Slovenia, there are more than 100 NRMs, mostly small (half of them count less than 20 members), reports Aleš Črnič (University of Ljubljana). There has been little conflict, and it is easy to register, although there have been attempts to make requirements for registration stricter—but the Constitutional Court turned down this proposal.

In the Czech Republic, despite some criminal cases involving minor NRMs, the situation has been peaceful in recent years, writes Zdeně Vojtišek (Karls-University, Prague). It may be worth mentioning that several articles mention local Neo-Pagan groups in the respective countries attempting to revive or recreate what they see as native religious beliefs. This revival is obviously also related to a quest for identity that may be linked to political attitudes in some cases, writes Mariya Lesiv (University of Newfoundland, Canada) in her article about the situation in Ukraine, where Paganism has been growing significantly. She expects those groups too closely associated with politics to have a limited future, while other ones may offer spiritual paths (including alternative views and practices in such areas as healing) that will find their place in the religious spectrum of the country.

(Religion & Gesellschaft in Ost und West, Birmensdorferstr. 52, P.O. Box 9329, 8036 Zurich, Switzerland – http://www.g2w.eu)