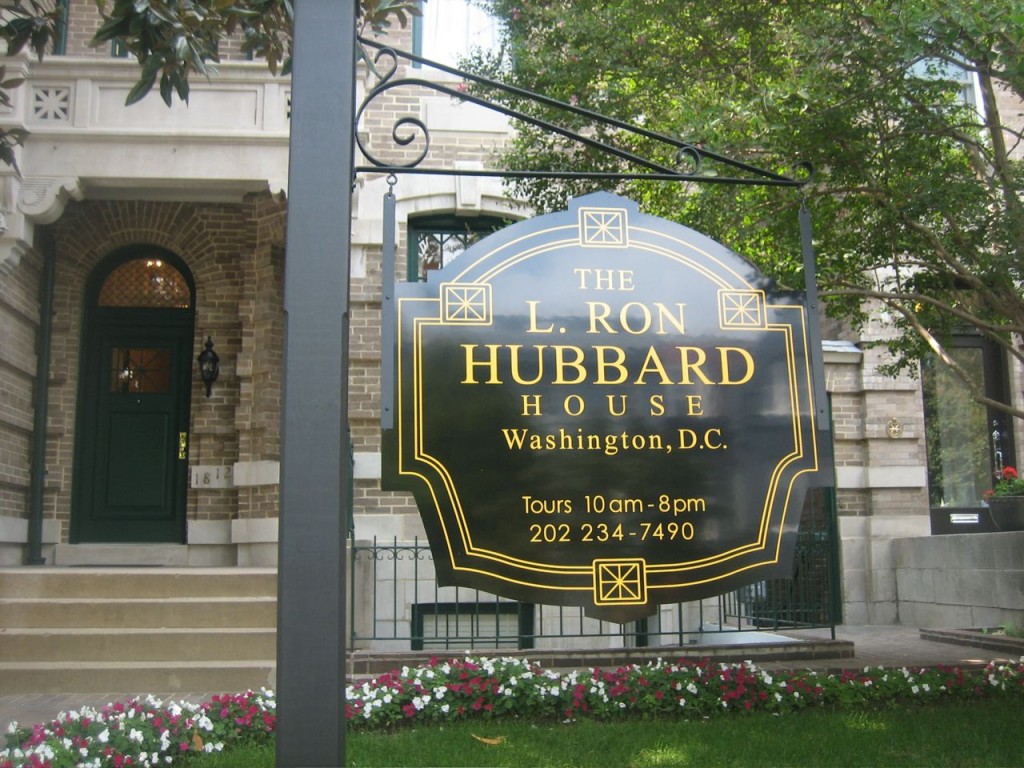

Numen, a journal of the history of religions, devotes much of its January issue to historical and current developments in the Church of Scientology. Editor of the section James R. Lewis notes that although there is increasing scholarly opinion that L. Ron Hubbard established Scientology as a religion for purely pragmatic reasons, the articles treat the church through the framework of traditional religion, particularly based on such themes as ritual, pilgrimage, and devotion to the founder. Scientology is viewed primarily as an individualized spiritual therapy, but contributor Richard V. Gallagher focuses on the church’s communal rituals. He finds that several elements of the Sunday service used by the presiding minister are consistently based around a limited canon of Hubbard’s writings. Another article looks at how key locations in the founding and development of Scientology can be understood as pilgrimage sites, including the L. Ron Hubbard Landmark Sites the church has established. For more information on this issue, visit: http://www.brill.com/numen

Sociologist Peter Berger’s new theory of the “two pluralisms” has been making the rounds in the scholarly world and is the subject of a symposium in the current issue of the social science journal Society (March/April). Also called the new paradigm (although that term is generally used for the market or the religious economies theory), this theory holds that modern individuals switch between religious and secular discourses, leading both to patterns of secularization and religious pluralism. Most of the articles support Berger’s thesis, with empirical accounts of religious pluralism in England, France, and Germany, but some authors question whether it just applies to modern society; anthropologist Robert Hefner argues that such internal pluralization of worldviews has marked traditional and non-Western societies as well. The article on France and Germany by Wolfran Weisse illustrates the complexity of the situation that the theory is trying to address. Weisse writes that in Germany, the “decline in church membership is flanked by a growing interest in questions which could be regarded as religious and growing numbers and identification with religion among those belonging to religions other than traditional Christianity in Germany.” He points to the German state of Hamburg which has engaged in extensive dialogues with Muslims, including a religious program where students are no longer taught within one tradition (Protestant or Catholic) but rather interact across different traditions. For more information on this issue, visit: http://link.springer.com/journal/12115

Sufism has increasingly been portrayed as the more mystical and benign, if not totally separate, offspring of mainstream Islam. But as the new book Living Sufism in North America (SUNY Press, $80) suggests, this neat distinction doesn’t capture the diversity of Sufi groups, teachings, and practices in the U.S. Author William Rory Dickson writes that Sufism accords so much influence to its leaders and their lineage of authority (the reason his interviews focused on them rather than members) that there can be almost as many different shades of Sufism as there are leaders. Dickson tries to dislodge other stereotypes about Sufism as well, such as the widely held view that the New Age movement has influenced a large segment of the faith in the U.S. Actually, even the most open and alternative Sufi group can remain deeply traditional in other aspects. Because the book mainly examines the ways in which Sufism has been adapted to its American context, it pays less attention to immigrant Sufi groups and Sufism’s reception and impact on the rest of American Islam. But Dickson, as suggested above, does vividly depict the unpredictable quality of Sufism in the U.S., finding Muslim traditions in the most Westernized and universalist of orders (such as those that do not require members to be Muslims) and syncretism (a statue of the Buddha, for example) in the most Islamic of orders.

Religion and Politics in the European Union (Cambridge University Press, $95), by political scientist Francois Foret, provides a unique look at how and to what degree religion interacts with the new structures of governance in Europe. The book is based on the first survey of the religious beliefs of decision makers (members of the European Parliament or MEPs) in the EU. The 166 interviews, which focused on voting and policy-making patterns and affiliations of MEPs, clearly reflect the secular orientations of these leaders’ respective nations, although these political elites are found to be more secular than average Europeans. Even as Foret finds that religion does not mobilize votes or create cleavages, with few visible denominational differences (such as Catholic versus Protestant; Muslims have not gained many MEP seats yet) among these politicians, “it does inform a European founding narrative.” Religion can also mark identity boundaries, as, for instance, in the case of opposition to Islamic Turkey being admitted to a still predominantly Christian EU.

Aside from the survey, the book looks at public controversies and what they say about the place of religion in the EU. For instance, the furor over the objections of Catholic MEP Rocco Buttiglione to gay rights legislation in the EU in 2004 suggests similarities with the culture wars in the U.S. But Foret argues that the pragmatic and secular outlooks of the MEPs points more in the direction of avoidance of religious conflict and tolerance, even if there are new outbreaks of public religion that will demand EU attention. Foret acknowledges, “American hawks and Muslim extremists are prone to see the EU’s lack of assertiveness on the international stage as a consequence of its lack of spiritual values.” But he concludes that its version of “mild secularism” will continue to make the EU an exception in world politics.