◼ We almost neglected to mention that this issue marks the thirty-fifth year of publishing Religion Watch. Some things do get better with age, and we hope RW is among them. We thank readers for their support and interest in this newsletter over the years. Our gratitude also goes out to the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University and its staff for providing a home for RW, as well as to associate editor Jean-Francois Mayer, especially for his assistance in putting out the newsletter during personnel changes earlier this year. We also take this opportunity to thank our departing copy editor Brian Bartholomew for his excellent work during the past two years and to welcome our new copy editor (and layout person) Micah Lambert.

◼ The open-access journal Religions (November 11) devotes a special issue to the future of Christian monasticism. Although RW ran an article from this compiled issue on monasticism in Africa, readers might be interested in the whole issue, which includes articles on new forms that include communities comprised of vowed and non-vowed members, men and women, and cloister-less or part-time membership. An article by Evan B. Howard sees the rise of less institutional forms of monastic life that were first expressed in the Middle Ages by the Beguines. These communities, as represented by such groups as the Nurturing Communities Network, Community of the Beatitudes, Missional Wisdom Foundation, the new hermit-based Ravens Bread, and the Order of Sustainable Faith (connected with the charismatic Vineyard churches), come from different denominational traditions but are marked by the common characteristics of tending not to take solemn vows or to abandon their professions before they join (though making a commitment to simplicity), blending active and contemplative faith, being self-governing, and being connected by networks of support. To download this issue visit: https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/10/12/643

◼ The responses of religious leaders toward the arrival of migrants have been mixed and not always consistent, and this also applies to Eastern Orthodox churches, leading Lucian N. Leustean (Aston University, Birmingham, UK) to launch a research project on forced migration, religious diplomacy and human security in Orthodox countries. Conducted in 2018, with workshops taking place in Belgrade and Kyiv, the project has led to a volume, edited by Leustean, Forced Migration and Human Security in the Eastern Orthodox World (Routledge, $175), on a topic on which little research material is otherwise available. Across the chapters, one can sometimes sense the tensions between the roles played by Orthodox churches as preservers of their respective national identities through turbulent national histories and their attempts to provide a Christian answer to humanitarian crises. The volume includes a chapter by RW associate editor Jean-François Mayer on the experience of migration for Orthodox migrants in Western Europe and how it has been leading them to make sense of their presence in new countries as well as its consequences for Orthodoxy worldwide.

According to Leustean’s observations, the forced migrations linked to the post-2011 Syrian refugee crisis and post-2014 conflict in Ukraine have led some clergy to populist discourses, but also led others to question the validity of nationalist discourses coming from some of their own hierarchs. In Greece, while Orthodox church leaders are definitely concerned about identity issues, do not promote the idea of multicultural societies, and show eagerness to prevent a demographic shift, several of them have also strongly advocated providing help to refugees and dealing with them humanely, as Georgios E. Trantas (Aston University) shows. On the other hand, in Bulgaria, in contrast with other religious denominations in the country, an address from the Synod of the Orthodox Church in 2015 put the emphasis on refugees as a threat to the nation and state security, as one can see in a chapter by Daniela Kalkandjieva (Sofia University, Bulgaria). “Orthodox churches do not have an overarching social policy on engaging with forced migration,” writes Leustean. Several churches have active social services, but they rely on national policies regarding migration, which means that those policies also influence the ways in which churches interact with migrants.

The eleven chapters in the volume offer case studies of Orthodox churches dealing with migration and humanitarian crises in countries such as Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania, without attempting  to elaborate a theoretical model. However, in the introduction, Leustean attempts to identify some key findings. First, the European Union’s policies are contentious and have been politicized in those countries, making the European approach to migration look like one of the elements in a clash between East and West. Second, religious communities (including Orthodox ones) have been among the first actors to respond to humanitarian crises and to provide help for refugees (sometimes having been requested to do so by authorities not having the resources and expertise to deal with these emergencies). Third, in the Donbas region of Ukraine, the buffer zone between both sides has not only generated violence, but also tolerance and reconciliation efforts by religious groups. Fourth, the attitudes of Orthodox churches as well as the competition among them have had “a direct impact on state support and engagement with human security.” Orthodox churches are learning. For instance, before the Ukrainian crisis, the Russian Orthodox Church had no well-developed strategy for addressing a flow of displaced people, but it then started to develop programs tailored to specific needs, as Alicja Curanović (University of Warsaw, Poland) writes.

to elaborate a theoretical model. However, in the introduction, Leustean attempts to identify some key findings. First, the European Union’s policies are contentious and have been politicized in those countries, making the European approach to migration look like one of the elements in a clash between East and West. Second, religious communities (including Orthodox ones) have been among the first actors to respond to humanitarian crises and to provide help for refugees (sometimes having been requested to do so by authorities not having the resources and expertise to deal with these emergencies). Third, in the Donbas region of Ukraine, the buffer zone between both sides has not only generated violence, but also tolerance and reconciliation efforts by religious groups. Fourth, the attitudes of Orthodox churches as well as the competition among them have had “a direct impact on state support and engagement with human security.” Orthodox churches are learning. For instance, before the Ukrainian crisis, the Russian Orthodox Church had no well-developed strategy for addressing a flow of displaced people, but it then started to develop programs tailored to specific needs, as Alicja Curanović (University of Warsaw, Poland) writes.

◼ That the recently published anthology Brazilian Evangelicalism in the Twenty-First Century (Palgrave Macmillan, $109), edited by Eric Miller and Ronald Morgan, is already being overtaken by developments in Brazil illustrates the rapidly shifting situation of evangelicals in that country. The book brings together American and Brazilian scholars of evangelicalism to give their assessments of evangelicals on several fronts—from evangelical feminism to evangelical environmentalism to church outreach in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. In an early chapter providing an overview of  evangelicals in Brazil (which includes Pentecostals there), Brazilian sociologist Alexander Brasil Fonseca argues that processes of pluralism and “de-traditionalizing” are underway among all churches. He points to the presence of a growing number of “syncretic evangelical churches,” where the older boundaries between Protestant faith and indigenous forms of spirituality are more porous, and observes that the dominant conservative prosperity gospel of many Pentecostals exists side-by-side with a theological discourse of “holistic mission,” stressing community development and social action. It should be noted that the book has its origins in a gathering of American and Brazilian scholars, many from evangelical backgrounds, to look especially at evangelicalism and social concern, accounting for the political undertone of the volume.

evangelicals in Brazil (which includes Pentecostals there), Brazilian sociologist Alexander Brasil Fonseca argues that processes of pluralism and “de-traditionalizing” are underway among all churches. He points to the presence of a growing number of “syncretic evangelical churches,” where the older boundaries between Protestant faith and indigenous forms of spirituality are more porous, and observes that the dominant conservative prosperity gospel of many Pentecostals exists side-by-side with a theological discourse of “holistic mission,” stressing community development and social action. It should be noted that the book has its origins in a gathering of American and Brazilian scholars, many from evangelical backgrounds, to look especially at evangelicalism and social concern, accounting for the political undertone of the volume.

Most of the contributors acknowledge the conservative political involvement of many evangelical churches, but none of them eyed the emergence of Jair Bolsonaro and how his conservative populism would register as enthusiastically among Brazilian evangelicals as his counterpart Donald Trump’s presidency has among evangelicals in the U.S. This is not to say that the holistic Brazilian evangelical movement is not a notable trend, but the tendency to plot a trend line in the direction of the political left is questionable. That said, political scientist Paul Freston does find that loyalty to evangelical politicians just because they are evangelical is weakening. It also seems that sectors of Brazilian evangelicalism do reflect its liberalizing counterparts to the north in some ways. American and transnational evangelical organizations, such as InterVarsity and the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students, have encouraged engagement with evangelical feminism in Brazil. The twin challenges of climate change and poverty are generating new activism, though the editors strike a cautious note regarding the claim that evangelical missions naturally foster democratic development and social reform wherever the faith is planted, adding that American evangelicals need to accept their limited understanding of Brazilian evangelicalism.

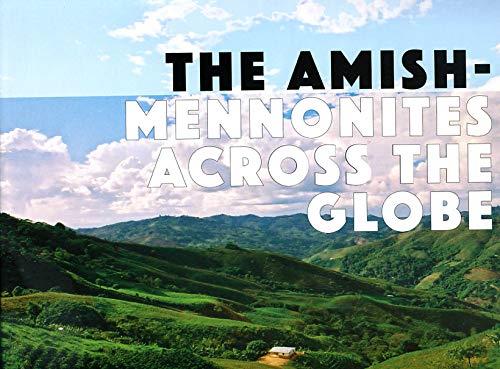

◼ The new book The Amish-Mennonites Across the Globe (Acorn Publishing, $45) follows the first volume The Amish-Mennonites of North America (Ridgeway Publishing, $35) in its visual, historical, and sociological portrait of this fascinating movement. An in-depth profile of the movement in the first book details the boundaries and identity of the Amish-Mennonites (AM), which are often unclear to members as well as outsiders. Authors Cory Anderson and Jennifer Anderson note that many Amish studies specialists have often viewed the movement as the “social residue” of the numerous schisms among the more familiar Old Order Amish and thus have classified such groups and congregations with their distant Mennonite cousins. The highly decentralized nature of the AM movement (although  there is the growth of new networks and associations) and lack of intergenerational continuity are additional reasons why they have gone under the radar. The authors (and photographers) of this pictorial portrait see the Amish-Mennonites best described as a conservative Amish movement that stands halfway in its distance from the modern world and technology (and the Amish are indeed distinguished among themselves by degrees of adaptions to modernity), most clearly reflected in its oldest (1920s) group, the Beachy Amish-Mennonites. The movement has 22,464 adherents (which include children and non-member attenders) in 201 churches.

there is the growth of new networks and associations) and lack of intergenerational continuity are additional reasons why they have gone under the radar. The authors (and photographers) of this pictorial portrait see the Amish-Mennonites best described as a conservative Amish movement that stands halfway in its distance from the modern world and technology (and the Amish are indeed distinguished among themselves by degrees of adaptions to modernity), most clearly reflected in its oldest (1920s) group, the Beachy Amish-Mennonites. The movement has 22,464 adherents (which include children and non-member attenders) in 201 churches.

Today, the Amish-Mennonites are distinguished by a high interest in missions and outreach (drawing converts), and by inclusion of “radical Mennonite” groups that have little historical connection to the Beachy Amish. The newest book also largely consists of photos and short profiles of AM congregations around the world, although these churches, which number 83 (with 4,796 members), tend not to use the AM label or actively seek to promote this identity apart from acknowledging common historical roots. It is the missions and church-planting emphasis of the AM that created most congregations across Latin America, the Caribbean, Eastern and Western Europe, Australia, and Africa (where the congregations tend to be larger, although that means about 100 members in this movement), although some are the result of Amish resettlement. Along with historical and sociological overviews and full-color photos of AM churches, the books also feature interesting thumbnail sketches of each congregation.

Today, the Amish-Mennonites are distinguished by a high interest in missions and outreach (drawing converts), and by inclusion of “radical Mennonite” groups that have little historical connection to the Beachy Amish. The newest book also largely consists of photos and short profiles of AM congregations around the world, although these churches, which number 83 (with 4,796 members), tend not to use the AM label or actively seek to promote this identity apart from acknowledging common historical roots. It is the missions and church-planting emphasis of the AM that created most congregations across Latin America, the Caribbean, Eastern and Western Europe, Australia, and Africa (where the congregations tend to be larger, although that means about 100 members in this movement), although some are the result of Amish resettlement. Along with historical and sociological overviews and full-color photos of AM churches, the books also feature interesting thumbnail sketches of each congregation.