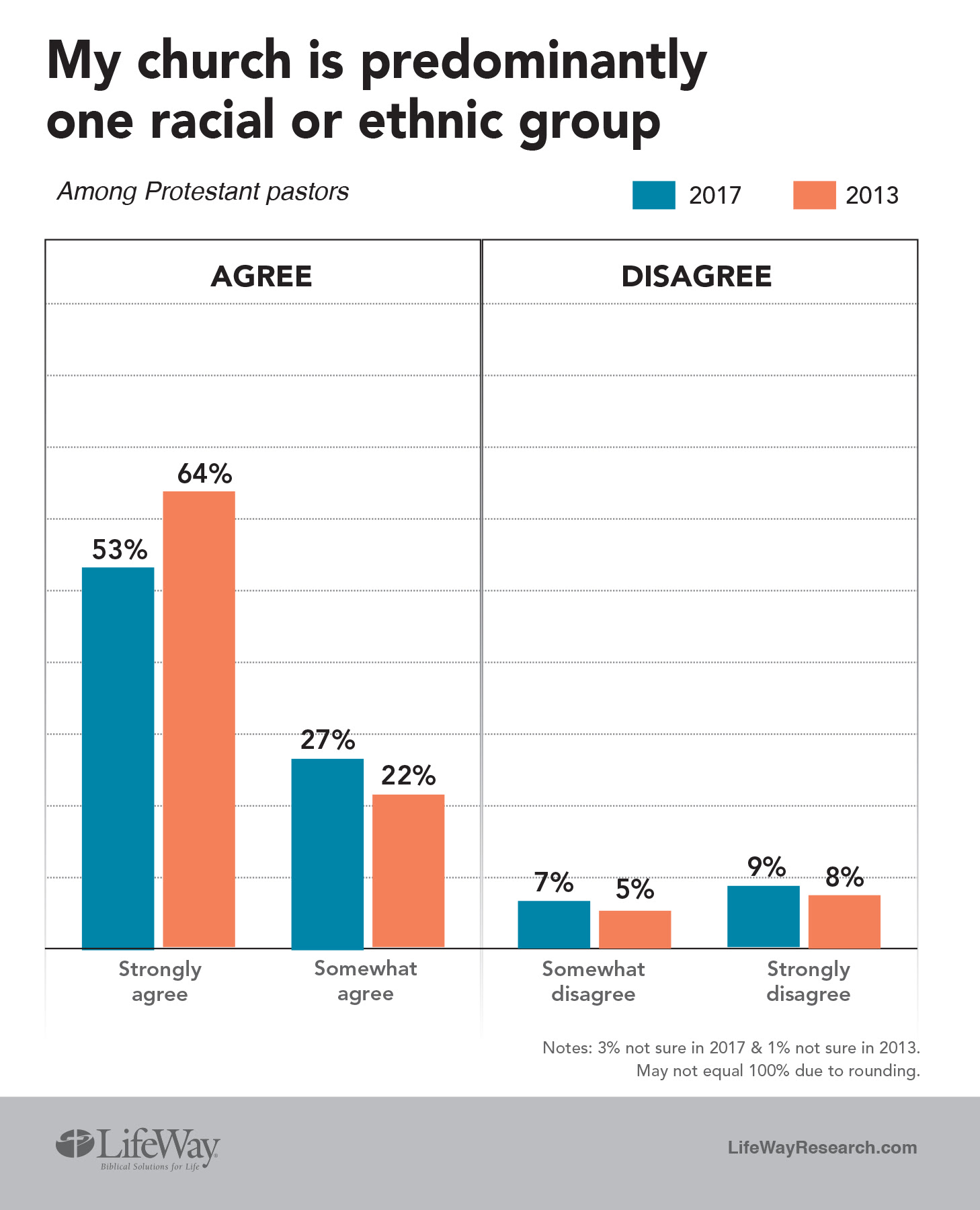

Despite anecdotal reports of minorities leaving white churches over their support of President Donald Trump, churches, especially evangelical ones, are gradually diversifying in race and ethnicity, according to a recent survey by LifeWay Research (March 20). The survey found that 81 percent of pastors report that their church consists largely of one racial group. While that figure is high, it was as high as 86 percent in a similar survey of both mainline and evangelical churches by LifeWay in 2013. Pastors of churches with 250 or more congregants were less likely (74 percent) to say their churches were mostly made up of one racial or ethnic group. Denominationally, Pentecostal pastors were least likely (68 percent) to say their churches were made up of predominantly one race or ethnicity, while Lutheran pastors were most likely (89 percent) to report such a lack of diversity. The LifeWay data do not include the actual racial and ethnic makeup of churches but only how pastors responded to the statement, “My church is predominantly one racial or ethnic group.”

(Lifeway Research, https://lifewayresearch.com/2018/03/20/protestant-pastors-want-churches-to-be-diverse-see-slow-progress/)

Non-denominational Christians are similar to Southern Baptists (who are thought to be typical evangelicals), although they tend to be more liberal about the Bible, younger, and more racially diverse, according to an analysis by Ryan Burge in the blog Religion in Public (March 7). Non-denominational Christianity has grown sharply in recent decades, and while members of these congregations have been considered largely evangelical in belief and practice, there has been little research on the phenomenon. Non-denominational Christians differ most notably from Southern Baptists in their age distribution, with 31.8 percent under age 40 (and a large age-range bulge between 25 and 35)—compared to 17.8 percent for United Methodists and 26.2 percent for Southern Baptists. The age difference may help explain the fact that non-denominational Christians are more ethnically diverse. Burge also finds that non-denominational Christians stand halfway between Southern Baptists and United Methodists on their views of the Bible (44 percent of them think the Bible is literally true compared to 60 percent of Southern Baptists and 28 percent of United Methodists). Perhaps reflecting their younger demographic, non-denominational Christians are more liberal than Southern Baptists on same-sex marriage but slightly more conservative on abortion. But on political stances in general, non-denominational and Southern Baptist Christians are very similar.

(Religion in Public, https://religioninpublic.blog/2018/03/07/nondenominational-protestants-are-basically-southern-baptists-with-a-few-caveats/)

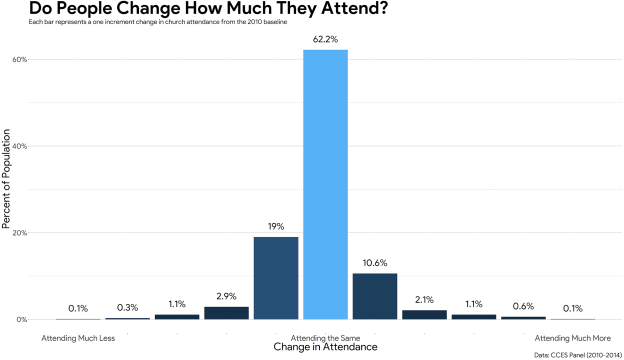

The pattern of Americans’ frequency of church attendance is remarkably stable, defying even conversion experiences, reports the Religion in Public blog (March 19). Ryan Burge analyzes the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (conducted in 2010, 2012, and 2014) and finds that 62 percent of respondents reported the same level of church attendance in 2014 as they did in 2010. But it is also the case that the number of people attending with less regularity is nearly 10 percent more of the population than those who are attending church more regularly. Burge finds it surprising that the traditional distinction between mainline and evangelical denominations is not associated with any difference in the percentage of individuals who are attending less. The most stable attendance pattern was among the Mormons while non-denominational Christians showed the most volatility. Of those who experienced a conversion in the years of the survey, only about one-third attended church more frequently.

(Religion in Public, https://religioninpublic.blog/2018/03/19/what-causes-people-to-attend-more-frequently-the-answer-is-not-becoming-born-again/)

The majority-religion of nations is a significant factor in Americans’ preference for giving foreign aid, according to a study in the journal Politics and Religion (online February). Previous studies have shown that religion can serve as a marker for threats attributed to a country, such as violence and conflict (often in the case of Muslim countries), shaping foreign aid priorities. Stanford researcher Alexandra Domike Blackman tested whether a country’s religion itself determines public support or opposition to giving foreign aid. She conducted two survey experiments (in 2014 and 2016) that asked respondents to rate a country’s suitability for receiving aid after reading random national attributes, which included religion. Blackman found that recipient country religion was a significant determinant of foreign aid preferences, “wielding more weight than many other determinants, such as a country’s ally or trade status.” While Muslim countries continued to receive the most “penalty” as a potential aid recipient, Buddhist countries also received negative responses, and the influence of recipient country religion on foreign aid preferences was particularly pronounced among Christian and evangelical respondents. “In this case, the relationship manifests itself as increased support for aid allocations to Christian recipient countries among Christian respondents in the United States.”

(Politics and Religion, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-religion)

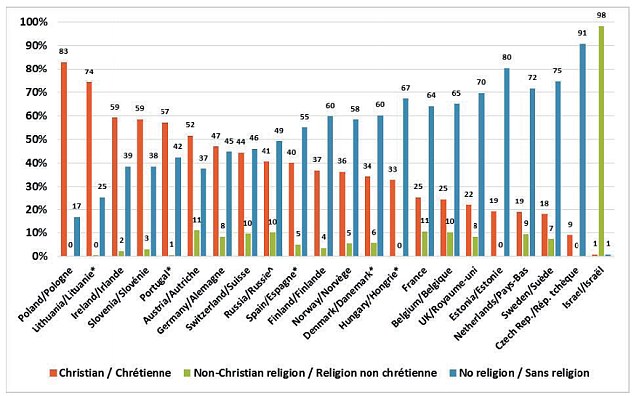

A new study of European and Israeli young adults finds a varying pattern of religious belief and practice, but the overall shape is one of increased non-affiliation, according to a new report from St. Mary’s University, Twickenham in London and the Institute Catholique of Paris. In 12 of the 22 countries studied by the European Social Survey (2014–2016), over half of young adults claim not to identify with any particular religion or denomination, though only one-third claim no faith in 19 of them. Both the two with the highest rates of non-affiliation (Estonia and Czech Republic) and the two with the lowest (Lithuania and Poland) are post-communist societies. Six of the “most Christian” countries are all historically Catholic-majority societies. In only four countries do more than one in ten 16-to-29-year-olds claim to attend religious services on at least a weekly basis: Poland, Israel, Portugal, and Ireland. However, there is not always a correspondence between attendance and affiliation: Lithuania, Austria, and Slovenia rank in the top five for affiliation but are among those countries registering in the single digits for attendance. A cluster of Northwestern European countries—France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the UK— plus Spain, are the highest “never attenders” among young people. When asking about rates of prayer, Poland, Israel, and Ireland were found to be the most “prayerful” countries, with half of Polish young adults saying that they pray at least once a week, while Estonia, Scandinavia, and the Czech Republic had the lowest number of young adults reporting that they pray.

(Europe’s Young Adults and Religion can be downloaded from: https://www.stmarys.ac.uk/research/centres/benedict-xvi/docs/2018-mar-europe-young-people-report-eng.pdf)

One of the first studies of environmentalism and religion in China finds that religious belief is associated with negative influences on private environmental attitudes while having a positive impact on public environmental behaviors through believers’ religious activities. The study, conducted by Yu Yang and Shizhi Huang and published in the online journal Religions (March 7), used data from the Chinese General Social Survey of 2013. The contradictory findings may be explained by the fact that religious believers tend to be from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and are more rural, less educated, and unaffiliated with the Communist Party and so are unschooled in environmentalist ideology that might inform their behavior. Yet being involved in a Chinese religious group had a positive relationship with environmentalism, since such organizations engage environmental issues, such as by running a recycling program. The positive effect was found among both traditional Chinese religions and newer Christian groups, though not among Muslims. Yang and Huang write that formal institutions, including laws and regulations, have failed to achieve desired environmental outcomes in China, and that religion may thus serve as a bridge between private and public environmental behavior (which is already taking place in arrangements between the government and various Buddhist groups).

(Religions, http://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions)

An analysis appearing in the journal Religions (March 22), based on the most recent Australian census of 2016, finds the Chinese community to be divided between religious believers and non-believers, often based on families’ region of origin and when they migrated from China. Yu Tao and Theo Stapleton find that in comparison with the general population of Australia, “members of the Chinese community are far more likely to claim that they do not have any religious belief,” making them more secular than even secularizing Australians. Among Australia’s religious Chinese, the most popular affiliation is among Christian denominations, followed by Buddhism. Regional variation is the strongest factor in the different rates of religious affiliation: while almost 58 percent of those reporting Taiwanese ancestry claim to have no religion, the figure is far lower for those with Tibetan ancestry, who overwhelmingly claim Buddhism as their religion. Those with both parents born in China have high “no religion” rates, especially those coming after the 1980s, when state secularization was the strongest.