⚫ According to a study of congregational ties by Jennifer McClure of Samford University, African-American congregations have the strongest social networks while older clergy in general have weaker ties. McClure, who presented a paper at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in St. Louis,  studied ties between 438 congregations in eight counties of the southeastern U.S. She looked at the reported frequency of social connections, joint events, and friendships among the lead ministers of these churches. She found that black pastors and those clergy between the ages of 40 and 54 had the most social ties, while those over 60 had fewer ties. McClure noted that just as strong social networks assist personal health, African-American churches’ more robust social networks may have led to their leadership in the civil rights movement.

studied ties between 438 congregations in eight counties of the southeastern U.S. She looked at the reported frequency of social connections, joint events, and friendships among the lead ministers of these churches. She found that black pastors and those clergy between the ages of 40 and 54 had the most social ties, while those over 60 had fewer ties. McClure noted that just as strong social networks assist personal health, African-American churches’ more robust social networks may have led to their leadership in the civil rights movement.

⚫ A new census of Pentecostalism finds its fastest growth areas to include new denominations tied to the prosperity gospel and megachurches and new apostolic networks stressing prophetic teachings and New Testament-style leadership offices. In a paper presented at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in St. Louis, J. Gordon Melton (Baylor University), a specialist on new religious movements, found that among the 300 Pentecostal denominations in the U.S., less than 25 are reporting their church statistics. While older Pentecostal denominations continue to show signs of growth, it is the Word/Faith movement that has seen the most significant growth, represented by televangelists Kenneth Copeland, Creflo Dollar, and Kenneth E. Hagin, and churches in the RHEMA church network, Liberty Fellowship, World Changers Church, and Believer’s Voice of Victory Network. Hagin’s son, Kenneth W. Hagin, has the largest network with 150 congregations, according to Melton.

The other growing sector among Pentecostal denominations is what is called the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR), teaching such concepts as the “seven mountains,” which urges believers to conquer secular spheres of society (such as art,  entertainment and politics), intercessory prayer, and spiritual warfare. Melton said that the fast-growing movement includes the Christian International Apostolic Network, the Federation of Ministers and Churches International, the International Coalition of Apostles, and the International Coalition of Prophetic Elders, led by Cindy Jacobs. Melton counted more than 100 different denominations and networks in the NAR. Many of these networks could be considered an “invisible religion,” with their headquarters based in the churches headed by “apostles,” of which there are about 300 in the U.S. Many of the congregations are in Texas, Florida, and Georgia, Melton concluded.

entertainment and politics), intercessory prayer, and spiritual warfare. Melton said that the fast-growing movement includes the Christian International Apostolic Network, the Federation of Ministers and Churches International, the International Coalition of Apostles, and the International Coalition of Prophetic Elders, led by Cindy Jacobs. Melton counted more than 100 different denominations and networks in the NAR. Many of these networks could be considered an “invisible religion,” with their headquarters based in the churches headed by “apostles,” of which there are about 300 in the U.S. Many of the congregations are in Texas, Florida, and Georgia, Melton concluded.

⚫ In contrast to the view that there is a “war on science” influenced by religion, recent research suggests that more specific battles are being waged by various groups on such issues as climate change, evolution, and vaccine safety. Jonathan Hill of Calvin University, presenting a paper on his research at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, looked at rates of “science skepticism” using the National Study of Religion and Human Origins (with 2,645 respondents). On the issue of evolution, religion was the primary driver of such skepticism, particularly among evangelical Protestants. But on the issue of climate change, it was politics that drove skepticism, with political conservatives showing more opposition to science claims than political liberals. On skepticism regarding the safety of vaccines, religion and politics were not found to matter; rather, it was age that was the most important driver, with young people being the most skeptical on this issue.

Hill concluded with the observation that only a small percentage of the population is skeptical on all three issues, suggesting that rather than an overall war on science there are “distinct drivers for each form of science skepticism.” He added that the idea that “cultural cognition”—the level of critical thinking and science education—drives support for scientific theories did not hold on the issues of evolution and climate change. Political conservatives and evangelical Protestants, respectively skeptical of climate science and evolution, actually scored higher on cultural cognition than those (liberals and non-evangelicals) who were not skeptical. On the safety of vaccinations, however, there did seem to be a correlation between deficits of cultural cognition and skepticism on the issue.

Hill concluded with the observation that only a small percentage of the population is skeptical on all three issues, suggesting that rather than an overall war on science there are “distinct drivers for each form of science skepticism.” He added that the idea that “cultural cognition”—the level of critical thinking and science education—drives support for scientific theories did not hold on the issues of evolution and climate change. Political conservatives and evangelical Protestants, respectively skeptical of climate science and evolution, actually scored higher on cultural cognition than those (liberals and non-evangelicals) who were not skeptical. On the safety of vaccinations, however, there did seem to be a correlation between deficits of cultural cognition and skepticism on the issue.

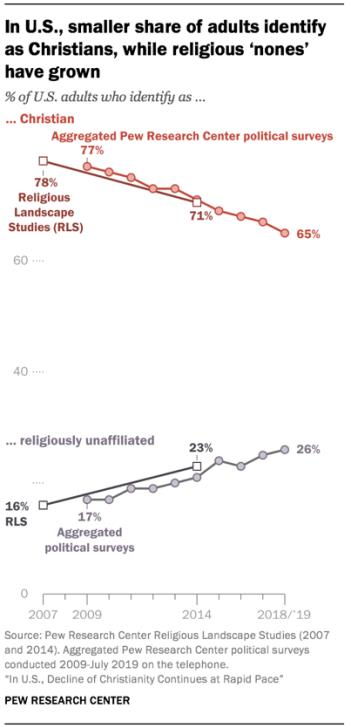

⚫ The proportion of non-affiliated American adults now stands at 26 percent, up from 17 percent in 2009, according to the Pew Research Center’s latest survey. Sixty-five percent of American adults describe themselves as Christians when asked about their religion, which is a decrease of 12 percentage points over the past decade. Both Protestantism and Catholicism are experiencing losses, with 43 percent of American adults identifying with Protestantism, down from 51 percent in 2009. Twenty percent of adults identify with Catholicism, down from 23 percent in 2009.

⚫ The proportion of non-affiliated American adults now stands at 26 percent, up from 17 percent in 2009, according to the Pew Research Center’s latest survey. Sixty-five percent of American adults describe themselves as Christians when asked about their religion, which is a decrease of 12 percentage points over the past decade. Both Protestantism and Catholicism are experiencing losses, with 43 percent of American adults identifying with Protestantism, down from 51 percent in 2009. Twenty percent of adults identify with Catholicism, down from 23 percent in 2009.

(The Pew study can be downloaded at: https://www.pewforum.org/2019/10/17/in-u-s-decline-of-christianity-continues-at-rapid-pace/pf_10-17-19_rdd_update-00-020/)

⚫ Conservative Christians publicly adopting liberal stances on such issues as immigration rely more on theological beliefs, while liberal Christians supporting conservative positions, such as prolife concerns, more often focus on their political aspects, according to a new study. In a paper presented at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, Baylor University sociologist George Yancey reported on his study of nine “progressive” Christian blogs and 11 blogs of conservative Protestants, where he focused specifically on how they supported issues not typically matching their theological orientations. The progressive blogs, which included those of Sojourner’s founder Jim Wallis and of theologian David Gushee, showed a greater willingness to attack other pro-life groups on political grounds and less willingness to press for pro-life legislation.

In the conservative Christian blogs, such as those of Southern Baptist leader Russell Moore and of Hispanic evangelical leader Samuel Moore, there was more citation of scripture and a greater reliance on theological beliefs in supporting views on immigrants’ rights and reform. There was little criticism of other immigrant movements or groups, while showing a non-radical approach; eight of the 11 blogs called for securing borders while supporting immigration reform for undocumented immigrants. Yancey concluded that in these cases of “mismatch” between theological beliefs and support for unpopular political movements and issues, there was a greater salience of theology for conservatives and of politics for progressives.

⚫ About three-quarters of mainline Protestant clergy shy away from preaching on controversial issues to congregants with a plurality of political views, according to a recent study. The study, conducted by Leah Schade of Lexington Theological Seminary and Wayne Thompson of Carthage College and presented at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in St. Louis, was based on a 2017 survey of 1,205 mainline clergy from 44 states. While the survey was based on a convenience sample, it matched the Faith Communities Today (FACT) survey in representativeness. It found that clergy were mostly liberal (62 percent) and registered Democrats who had voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016 (also 62 percent), but that many served in “purple zones”—congregations having a mix of “blue” and “red” political sentiments. Schade and Thompson found one-quarter of these clergy saying they preached on controversial issues rarely or never, half saying they did a few times a year, and another quarter saying they did so frequently. The more controversial issues most frequently preached on were race, poverty, hunger, and homelessness, while abortion, fossil fuels, a critique of capitalism, and LGBTQ issues were more often avoided in the pulpit.

As to why controversy was so often avoided in preaching, 23 percent said they preferred a different setting for approaching these issues, 20 percent said they were concerned about church division and conflict, 17 percent feared pushback by congregants, and 17 percent said they were not equipped to deal with such issues. As to what these clergy actually experienced when they did preach on controversial issues, 37 percent heard reports of angry congregants, 32 percent received angry remarks, 21 percent heard of members quitting, and 16 percent heard of members withdrawing their offerings to the church, while only a small percentage heard of calls for them to resign (five percent) or were actually let go (one percent). Schade and Thompson were surprised to find that it was in the larger congregations where clergy had more secure positions that they were more likely to preach on more controversial issues. The researchers explained that having full-time positions with larger memberships provided a cushion where preaching on such issues was less risky to their ministry and careers. United Methodist and Lutheran clergy were more likely to preach on controversial issues, while those from American Baptist churches and even the very liberal United Church of Christ were less likely to do so.

⚫ A qualitative study of United Methodist seminarians finds them reluctant to leave the denomination or forsake their plans for ordination, even as they register a high degree of uncertainty about their place in a church body divided over questions of sexuality. It has often been reported that the recent decision of the denomination to retain and strengthen prohibitions against gay clergy will inevitably lead to a schism of liberals from the church. But a study by David Eagle (Duke University) of 15 recent seminary graduates who were planning to enter the ministry prior to the United Methodists’ 2019 adoption of what is known as the “traditional plan” to bar LGBTQ clergy suggests more ambivalence about such a departure. In in-depth interviews, Eagle found that most of these seminarians took a “wait-and-see” approach, hoping for a possible redressing of the issue in 2020 even as they put their career plans on hold. They were uniformly opposed to the traditional plan and accepting of LGBTQ clergy, but they also saw the difficulty of creating inclusivity in the denomination. Eagle found that they adopted a strong “us versus them” mentality in viewing the denominational situation.

Their harshest views were reserved for American church leaders who supported the plan, accusing them of exploiting international members (who have been opposed to LGBTQ clergy) for their supposed white supremacy and conservatism. The seminarians saw these international members (who mainly reside in the global South) as being largely innocent pawns of a “colonialist” takeover by white American leaders and members. The “exaggerated portrait of conservatives” in these seminarians’ narratives suggested the “intractability of this debate.” Liberals appear to be using conspiratorial terms and to show little interest in including conservatives in the church or engaging in conversation with them. “It’s hard to see how the United Methodist Church can remain unified,” Eagle concluded.

Their harshest views were reserved for American church leaders who supported the plan, accusing them of exploiting international members (who have been opposed to LGBTQ clergy) for their supposed white supremacy and conservatism. The seminarians saw these international members (who mainly reside in the global South) as being largely innocent pawns of a “colonialist” takeover by white American leaders and members. The “exaggerated portrait of conservatives” in these seminarians’ narratives suggested the “intractability of this debate.” Liberals appear to be using conspiratorial terms and to show little interest in including conservatives in the church or engaging in conversation with them. “It’s hard to see how the United Methodist Church can remain unified,” Eagle concluded.

⚫ Filipino church leaders’ attitudes toward President Duterte’s “war on drugs” are determined more by their moral views of drug addicts than their denomination, according to new research. The Duterte campaign, involving violence and death penalties against users and sellers, has been largely supported by Filipinos (both in the Philippines and in the diaspora), though leaders of the Catholic Church have registered the strongest opposition to these policies. In a qualitative study of churches and religious leaders in the Manilla area, the findings of which were presented at the October meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in St. Louis, Jayeel Cornelio and Erron Medina found a range of views among church leaders on the validity of the war on drugs, with some closely reflecting Duterte’s policies and even supporting the death penalty as a weapon in fighting drug use. Other church leaders saw addicts, especially affected young people, as victims of poverty and of the drug trade and called against state violence to stop drug use. The researchers found that while the denomination of the church leaders mattered, it was more often their views on drug addicts’ spiritual status and the degree of their pastoral experience with them that determined their attitudes toward the war on drugs. Cornelio and Medina concluded that the silence of many church leaders on the ethical implications of the war on drugs stemmed from the absence of a public theology that would help people deliberate on the common good.