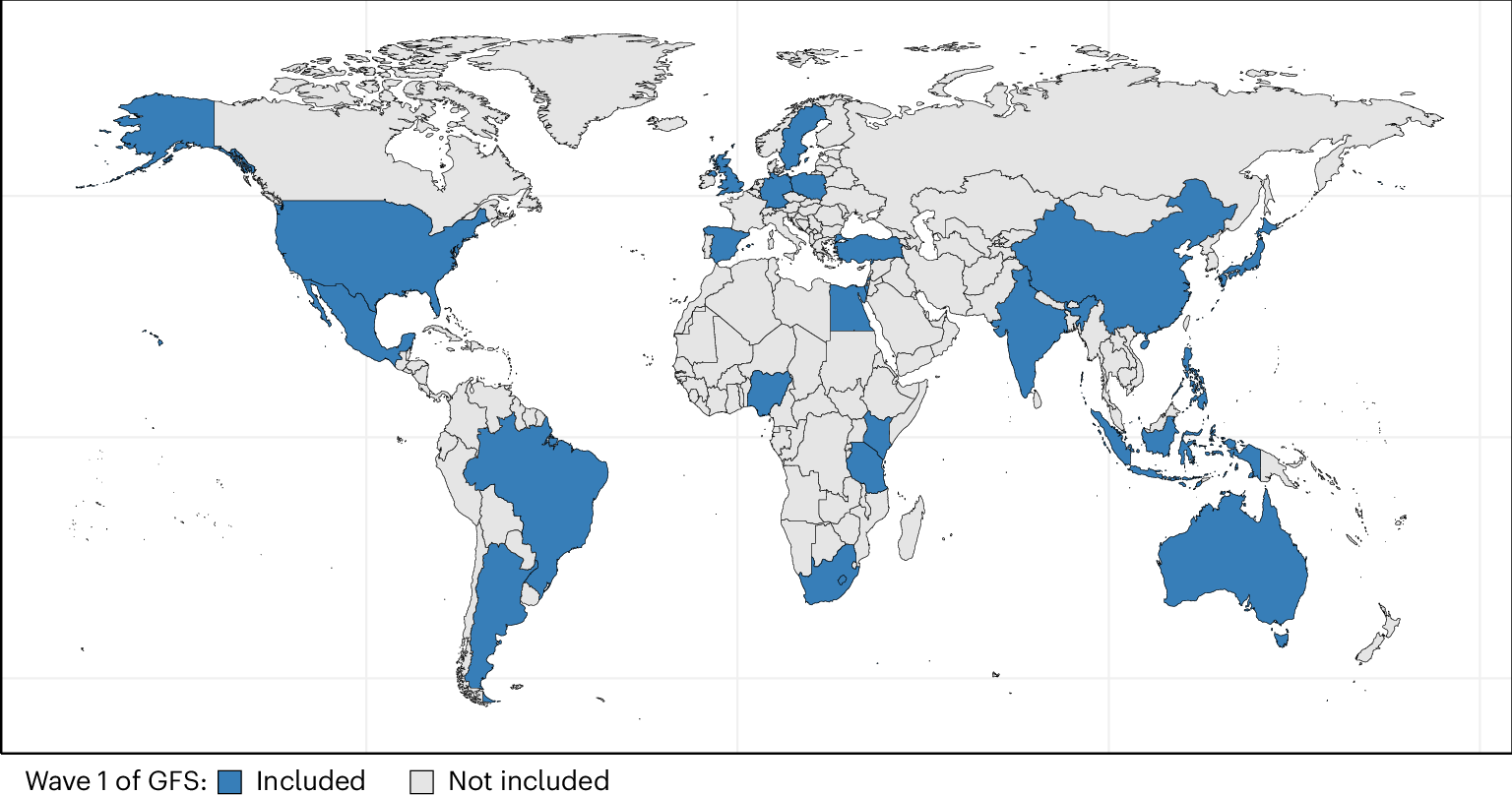

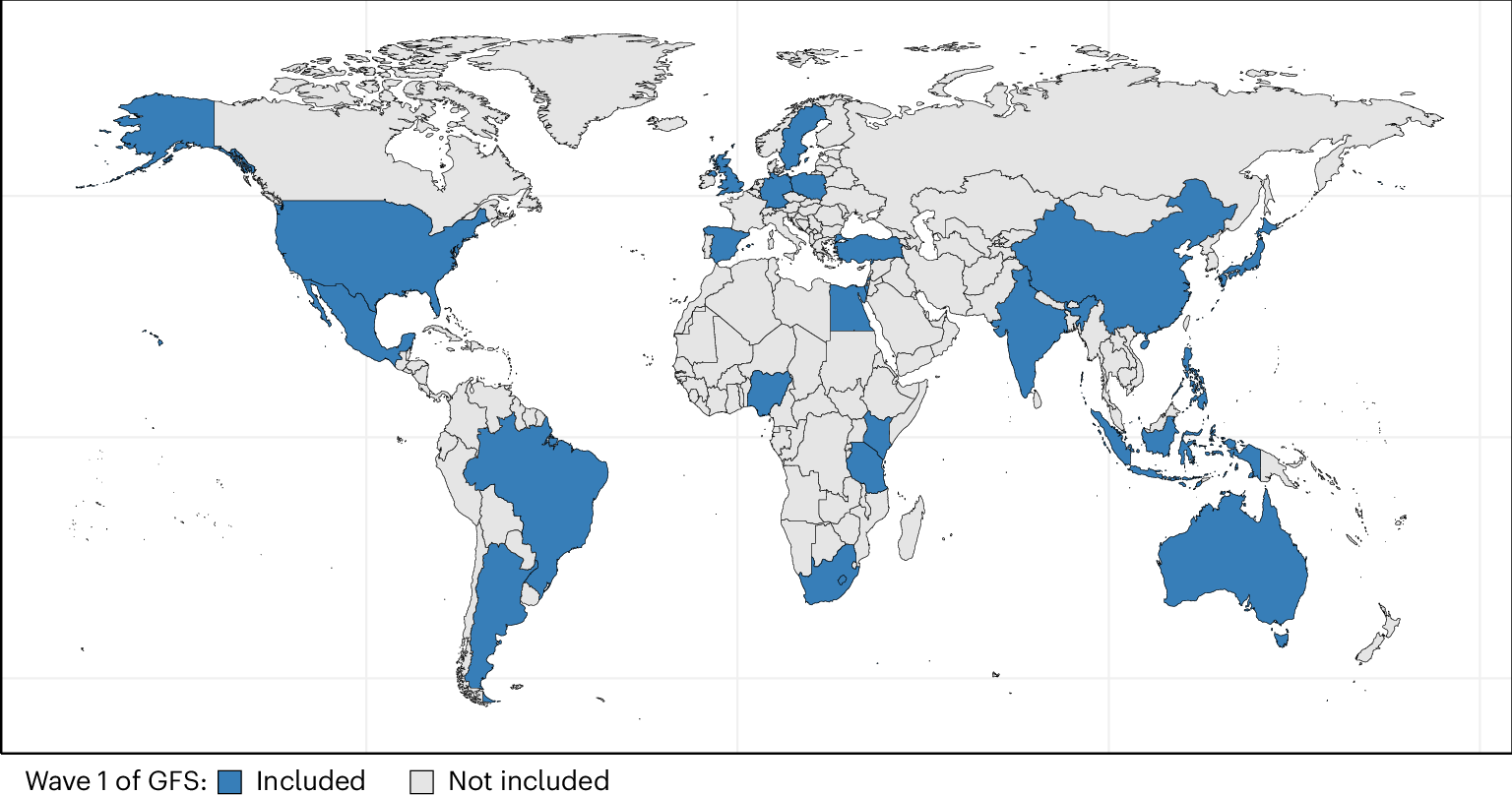

A major new study finds a strong association between religious identity and human flourishing. The Global Flourishing Study (GFS) study, a longitudinal survey across 22 countries, was conducted by Baylor University and Harvard University, with its initial findings presented at a recent conference at the Gallup world headquarters in Washington, which RW attended online. Employing a 10-point scale, the study found a 0.81-point gap in composite flourishing between those who attended religious services at least weekly and those who never attended. Regular attenders were also significantly more likely to report volunteering, showing love and care to others, and having a higher sense of meaning and purpose, among other aspects of a good life. That religious service attendance in particular is a powerful predictor of health and well-being was seen in Indonesia, which had the highest scores in the GFS for many aspects of flourishing while being a highly religious society, with 98 percent of the population identifying as either Muslim or Christian and 75 percent attending religious services at least weekly. Countries with lower religious attendance, such as those in northern Europe, even when they have higher GDP per capita, often have lower “composite flourishing” scores, which cover such domains as self-rated happiness, health, meaning, character, relationships, and financial security.

Even after factoring in self-rated financial security, more religious middle- and low-income countries, such as Indonesia, Mexico, Kenya, and Tanzania (where GDP per capita in 2023 was $1,211), have higher average composite flourishing scores than less religious affluent countries, such as the U.S., Sweden, Germany, and Japan. However, the researchers note that, this early in the study, it is difficult to assign a causal role to religious involvement in accounting for flourishing. For instance, while Turkey and Indonesia are both overwhelmingly Muslim countries, the former had the second-lowest mean score for composite flourishing. In Tanzania, 73 percent of Christians (half of whom are Roman Catholic) said they had had “a life-changing religious experience,” whereas in deeply Catholic Poland, only 9 percent of Christians reported the same.

(Results and analyses of the first wave of the GFS study are freely accessible from the journal Nature: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44220-025-00423-5)

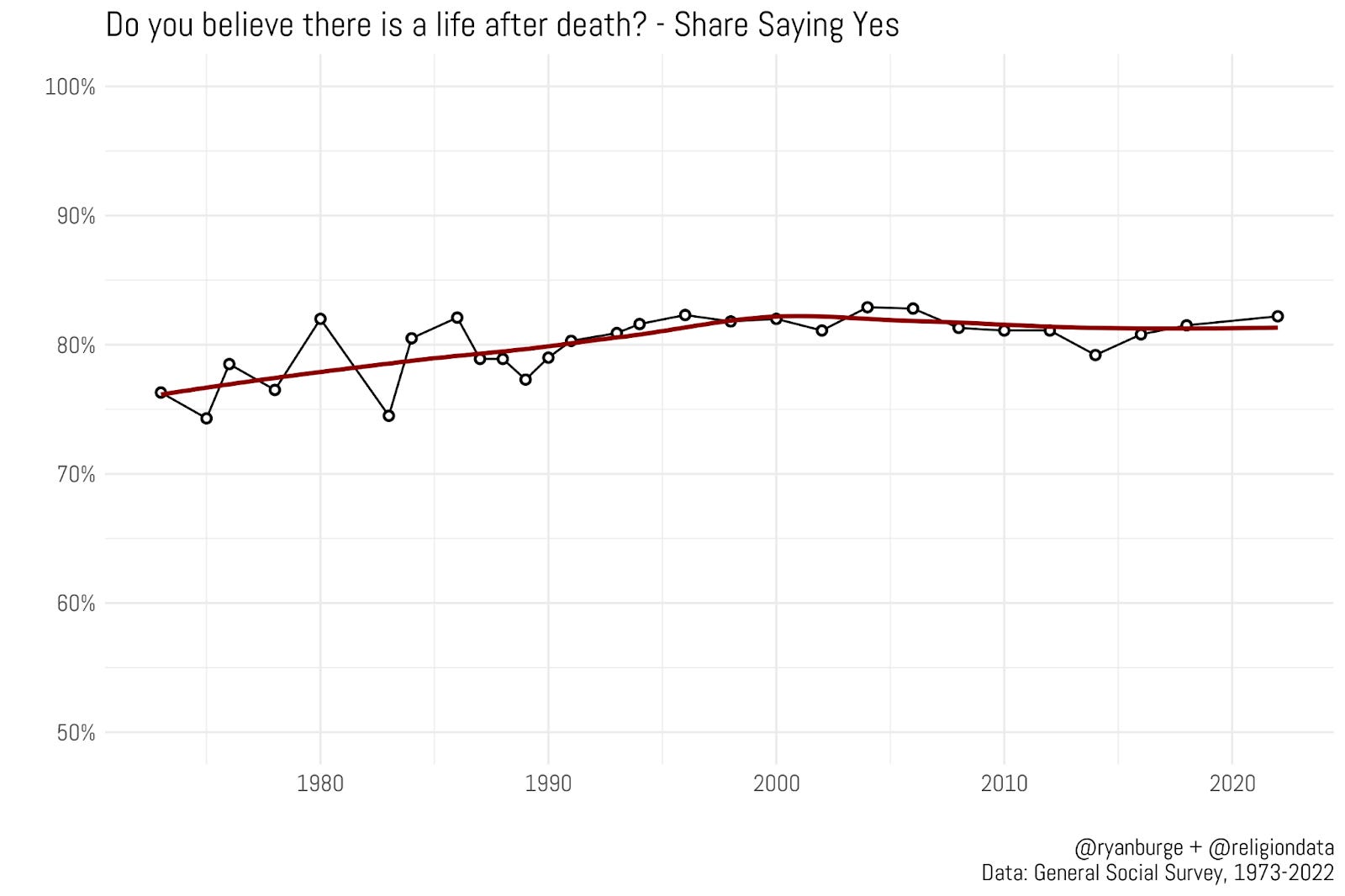

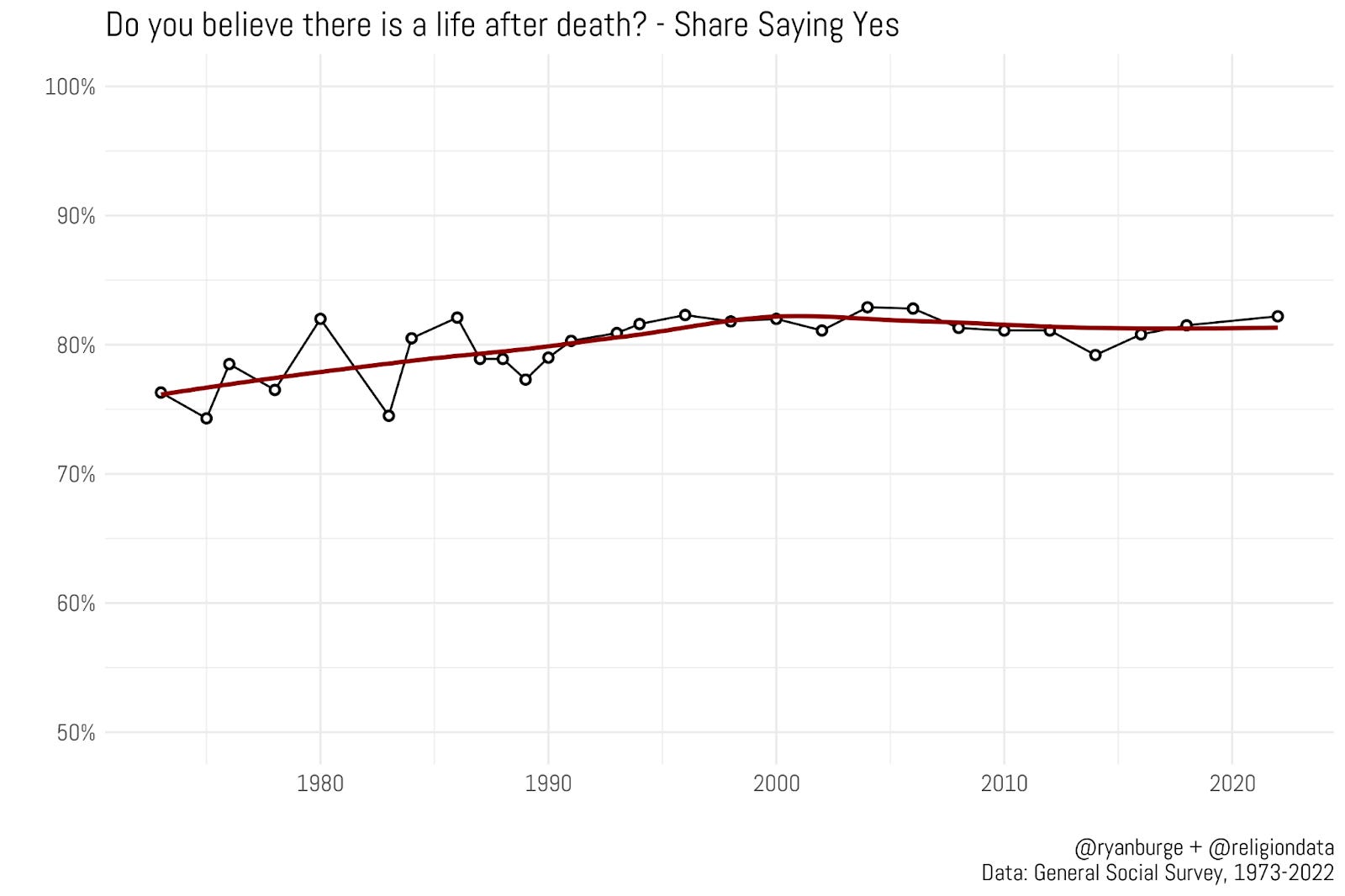

Belief in life after death has remained one of the most resilient beliefs, even in secularized countries, and it seems to be increasing in the U.S. In his Substack newsletter Graphs about Religion (April 17), Ryan Burge analyzes five decades of data on belief in the afterlife from the General Social Survey. Seeing no dramatic upward or downward movement of the trend line, he finds that “belief in an afterlife is incredibly robust…and almost completely unchanged over the entire time series. In that first data collection in 1973, about 76 percent of folks believed in something beyond this life. But by 1990, that figure had crept up to just about 80 percent and it continued to rise very slowly from there.” From 2000 to 2022, “the estimates are all basically the same. Even today, the share of Americans who believe in life after death is 82 percent.” Burge finds it striking that there are not many differences in belief in an afterlife among the most and least educated in the sample. This was as true in 1973 as it is in 2025. Actually, when controlling for other factors, “an educated person was more likely to believe that there was life after death than someone with less education.”

While there is a noticeable drop in belief in an afterlife among those born in the 1960s compared to previous decades, the next three cohorts don’t show a consistent trajectory. For each of those groups, belief in life after death is about 83 percent. People born in the 1980s are just as likely to believe in life after death as people 30 or 40 years earlier. In considering the 20 percent of Americans who don’t believe in an afterlife, Burge notes that as time has passed the share of the non-affiliated (“nones”) who believe in an afterlife actually rose. By 2000, it was at least 60 percent, and it has remained at that level over the last two decades. He argues that the nones from decades ago were more “hardcore” in their secularism, whereas today they are less committed to secular beliefs, Many of them may have been turned off from organized religion because of its political involvement, yet they seem to have retained their spirituality.