-

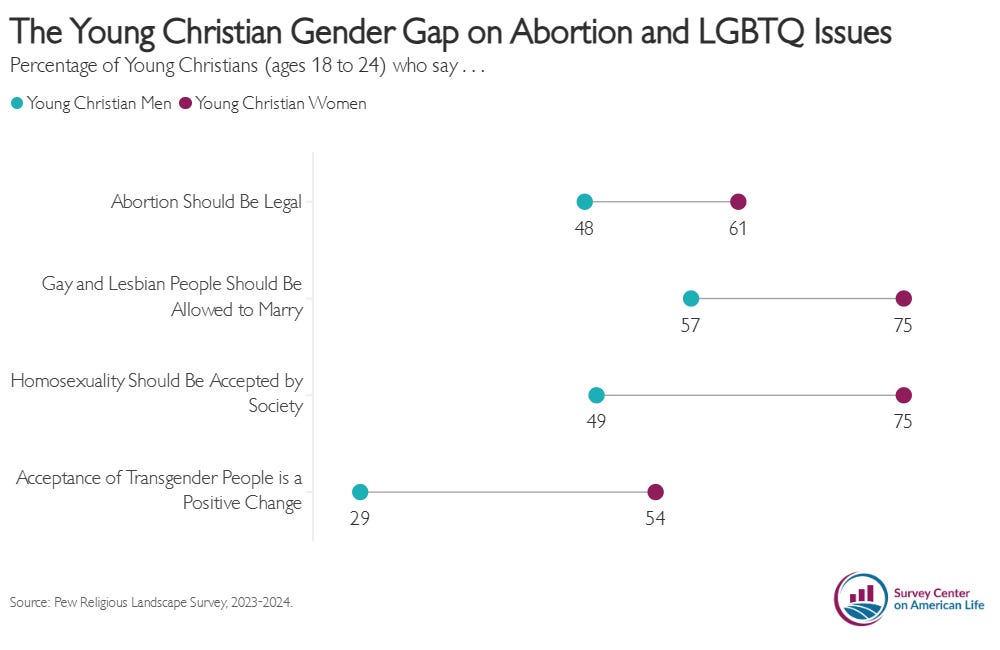

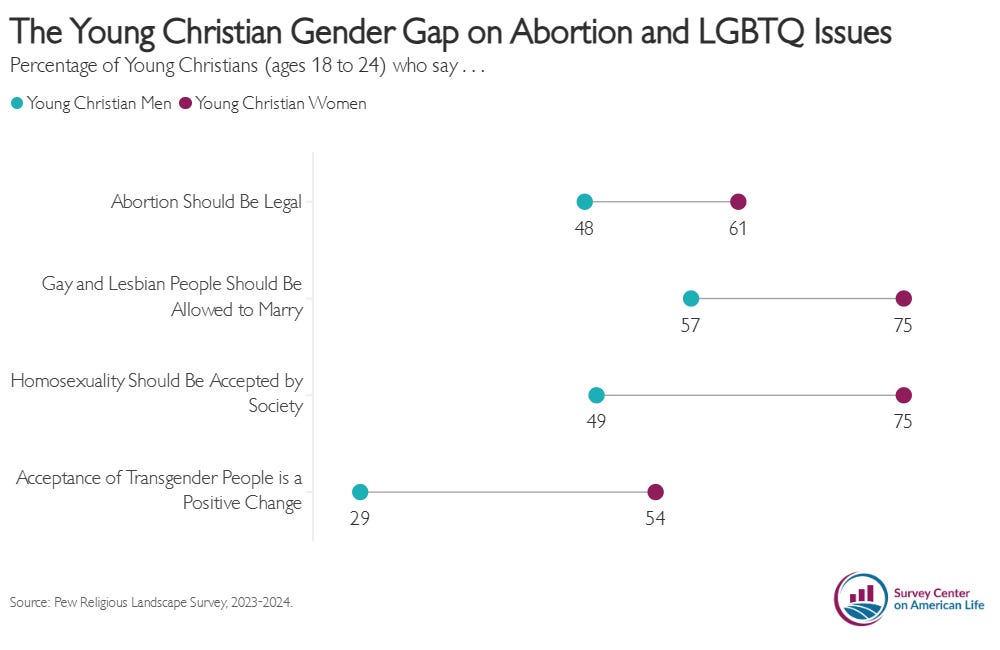

The gender gap in churches is growing, with young men and women differing on social and moral issues. In the Substack newsletter American Storylines, pollster Daniel Cox analyzes the recent 2024 Pew Religious Landscape Survey and finds that more than 6 in 10 (61 percent) young Christian women say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Less than half (48 percent) of young Christian men say the same. Young Christians are less supportive of legal abortion than their peers, but the drop-off in support is substantially larger among men. On homosexuality, the gap is even wider, with three-quarters of young Christian women saying that homosexuality should be accepted by society, a view shared by less than half (49 percent) of young Christian men—a 26-point gap. Young Christian women are also far more likely than men to support allowing gay and lesbian people to marry (75 percent vs. 57 percent). A majority (54 percent) of young Christian women say greater acceptance of transgender people is a positive development, but only 29 percent of young Christian men agree. Cox notes that there is some indication that the gender gap among young Christians has gotten larger. A decade earlier, “young Christian men and women were more aligned than they are today. In 2014, less than half of young Christian men (42 percent) and women (45 percent) said abortion should be legal in all or most cases,” he writes.

This does not necessarily mean that young women are moving leftward on all these issues. Aside from the issue of abortion, young Christian women have hardly changed their views over the last decade, while young men have become less supportive. Cox finds that young Christian women are also more progressive on economics and the role of government. Three-quarters of young Christian women would prefer a larger government, offering more public services. Nearly 6 in 10 young Christian men say the same. Since there are not wide differences between young men and women on attendance, denomination and other practices, Cox argues that young Christians are being exposed to the same cultural divides afflicting secular young people. “Even if they attend the same church, the social context for young men and women is still quite different. Young Christian women have many more close friends who identify as LGBTQ than men, an experience that has a considerable influence on policy views.” The way young men and women are segregated on social media and exposed to different content may reinforce gender divisions. It may also be the case that marriage-rate declines have led to less shared perspectives between men and women.

- A recent study finds that during the Covid pandemic, U.S. counties with greater shares of Christian adherents experienced faster employment recovery, a higher recovery of companies, and modest but positive wage effects. Findings from the research by Christos Makridis (Arizona State University) and Byron Johnson (Baylor University) were presented at the early-March meeting of the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture (ASREC) in Washington, DC, which RW attended. Using data from the Quarterly Census of Employment (2019–2023) and the Religion Census (2010, 2020), the researchers looked at the relationship between within-county religiosity and indicators of economic performance during the pandemic. Those counties with lower shares of Christian adherents showed greater negative effects in these areas. The weakest effect among the higher-share counties was the growth of employment. The study controlled for such variables as rates of social capital and median household income and took into account the declines in Christian adherence between 2010 and 2020. Makridis and Johnson conclude that involvement in religious social networks enhanced community resilience, with religious communities generating “trust, ethical business practices, and labor efficiency.”

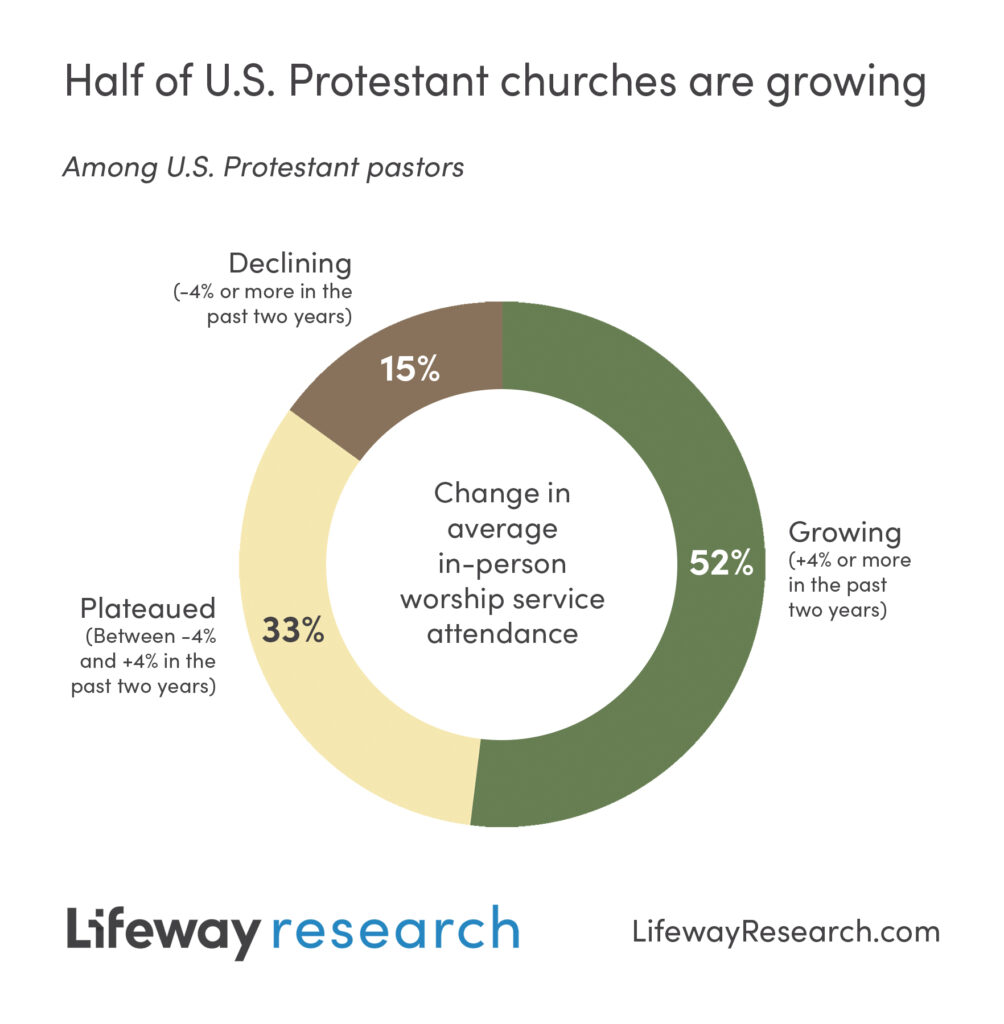

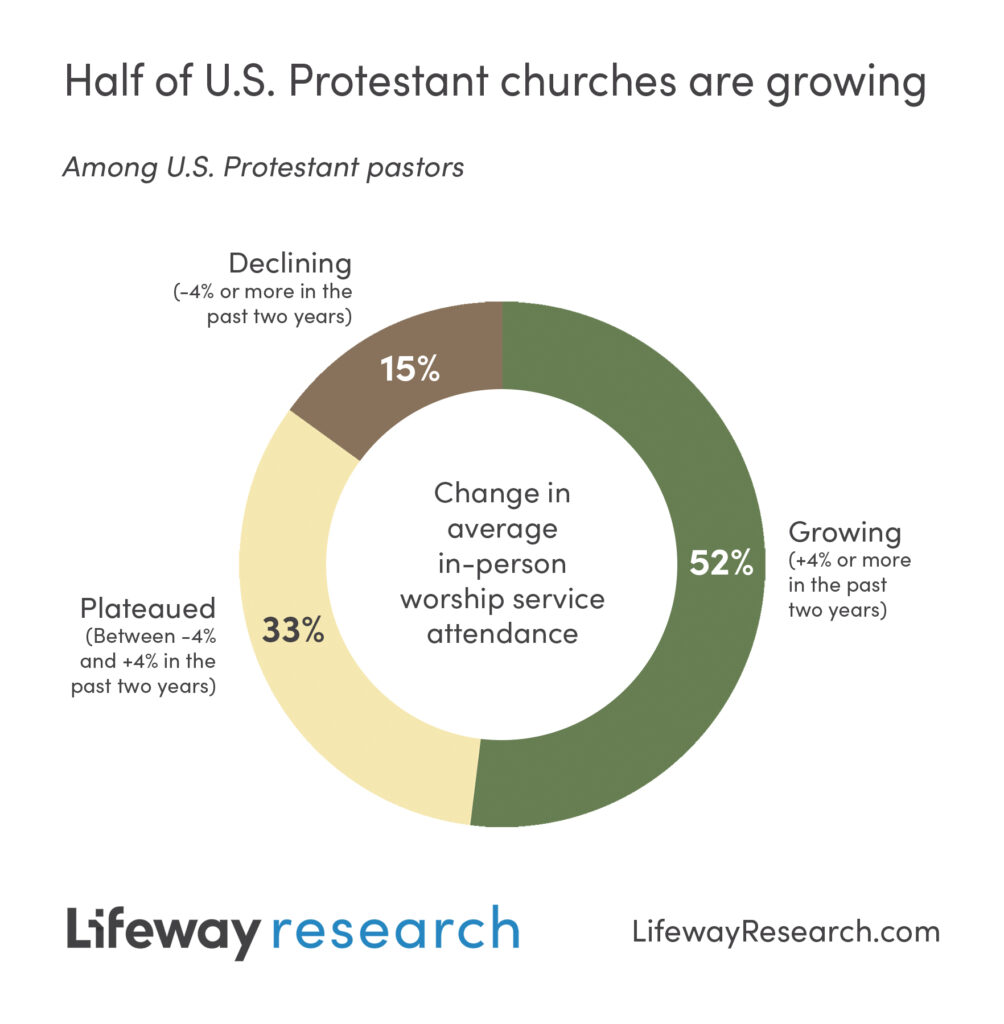

- Protestant pastors say their churches are growing, but some warning signs remain about their congregational future, according to a study by Lifeway Research. The survey finds that Protestant churches are almost evenly split between those that have grown within the past two years and those that have plateaued or lost attenders. About half of the sampled congregations (52 percent) increased their worship service attendance by at least 4 percent in the past two years. The other 48 percent have either remained within plus or minus 4 percent since 2022 (33 percent) or declined by at least 4 percent (15 percent). “Clearly, the last two years of attendance growth was aided by people returning to regular attendance after being away since the start of the pandemic,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research.

He adds that “Most pastors wish they had returned earlier, but their attendance is a source of optimism, though future growth will need to come from brand new contacts.” Overall, the large congregations are growing larger and the small keep getting smaller. The study found that the larger the congregation, the more likely it was to be growing by 4 percent or more: 62 percent of those churches with more than 250 in attendance and 59 percent of those with 100 to 250 grew by at least 4 percent, while this was true for 45 percent of those with 50 to 99 in attendance and only 23 percent of those with fewer than 50. Evangelical pastors are more likely than mainline pastors to say their church is growing (57 percent v. 46 percent). Denominationally, Holiness (63 percent), Pentecostal (62 percent), and Baptist congregations (59 percent) are more likely than Methodist (43 percent) and Lutheran churches (37 percent) to be experiencing growth of at least 4 percent.

(The study can be downloaded here: https://research.lifeway.com/2025/03/18/half-of-churches-experiencing-post-pandemic-attendance-growth/)

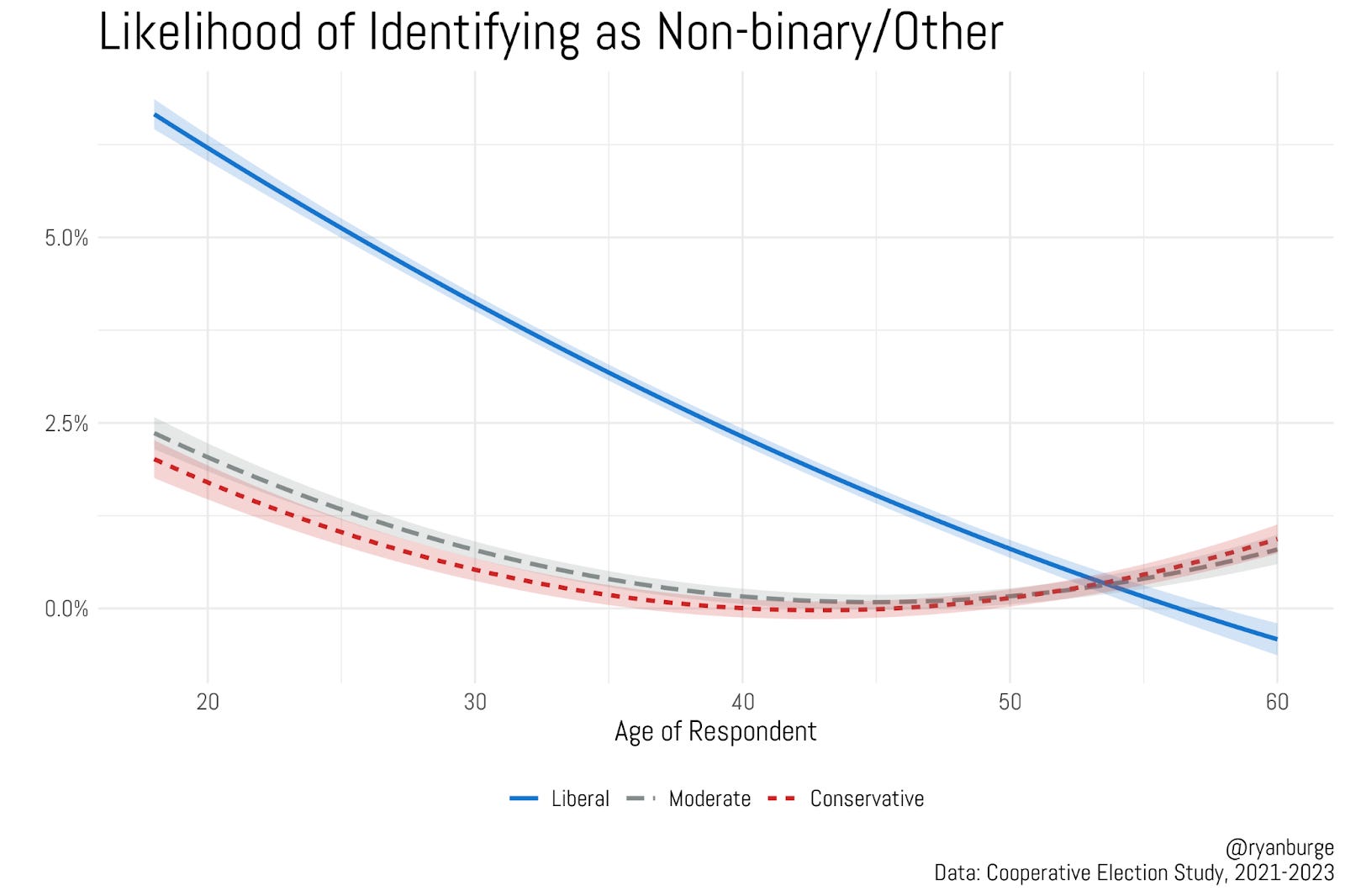

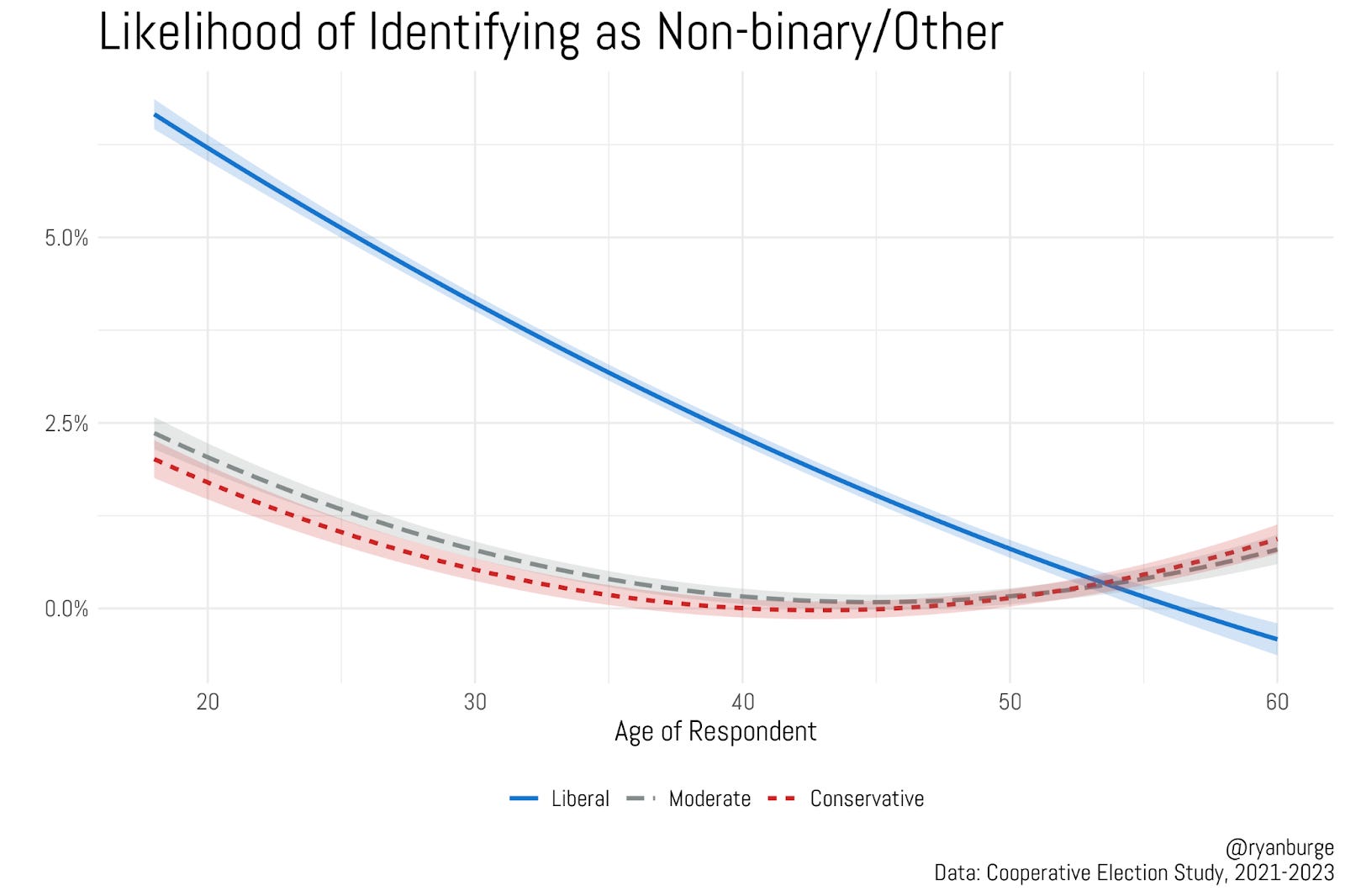

- Transgender people are significantly less religiously affiliated than other Americans, according to an analysis of Cooperative Election Survey data by Ryan Burge in his Substack newsletter Graphs about Religion (March 17). Among people who identify as “non-binary,” only 13 percent say they are Protestants. That’s nearly 20 points lower than the rest of the sample. Additionally, only 7 percent are Catholic, compared to 18 percent of the male/female sample. As might be expected, the non-religious percentages are much higher among this group; about 60 percent of the non-binary/other group said they were atheist/agnostic/nothing-in-particular, compared to 35 percent of the male/female sample. Among the non-binary/other sample, 57 percent said that they never attended religious services—which is 23 points higher than the male/female part of the sample; when the “seldom” option is included, close to 80 percent of the transgender respondents reported going to church less than once a year.

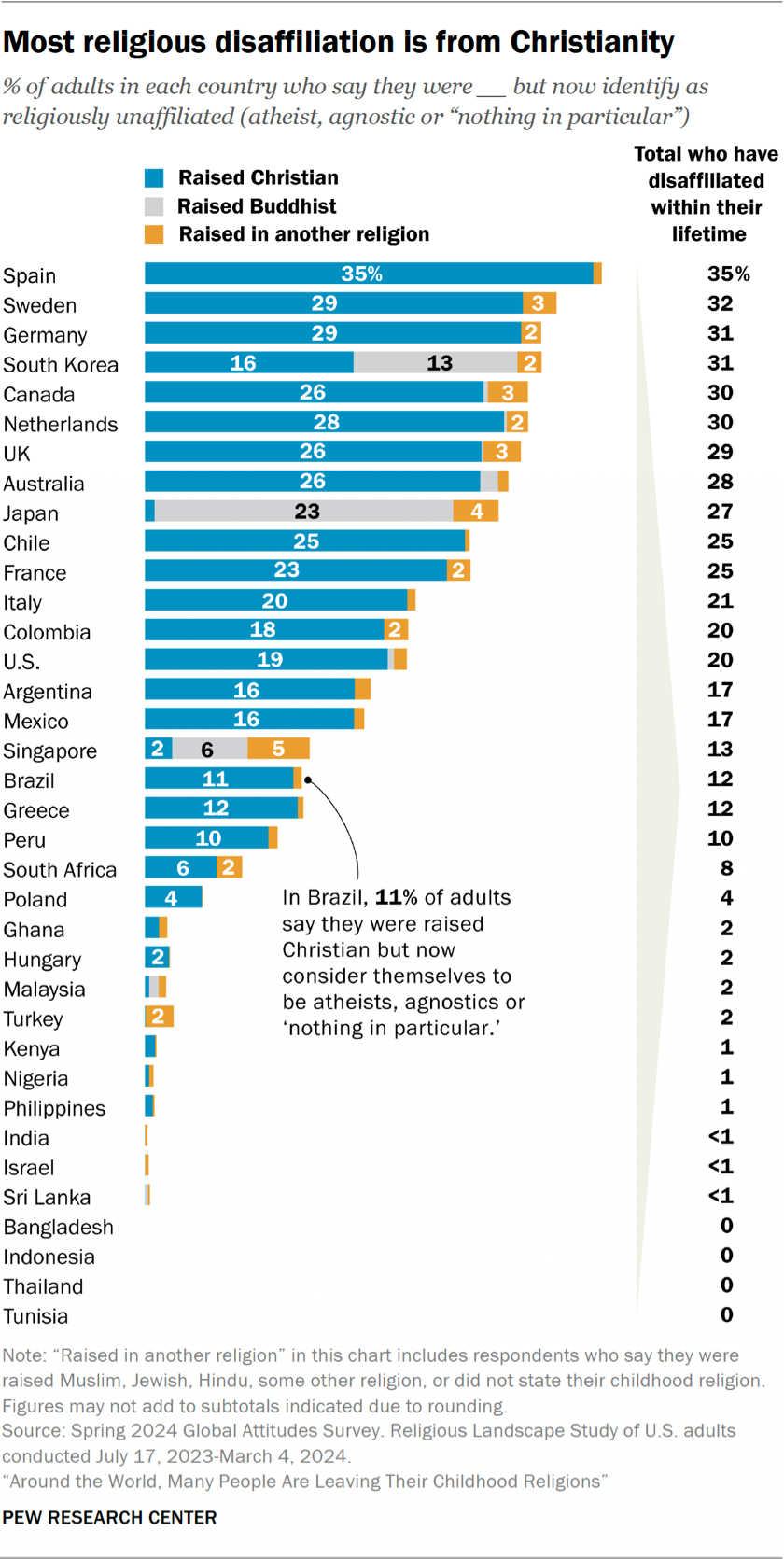

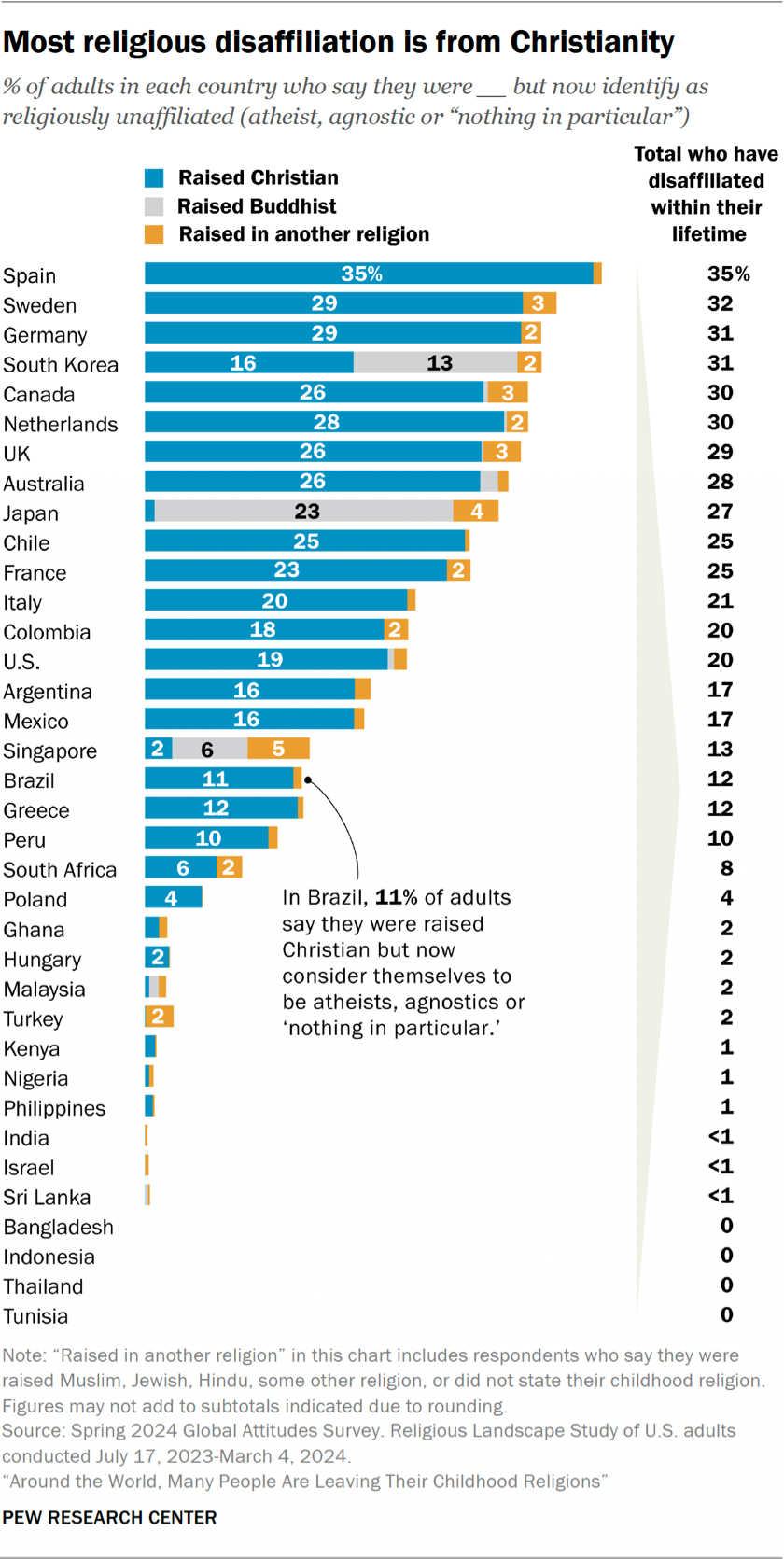

- A new Pew study finds that as much as 20 percent or more of all adults around the world have left their childhood religion, with the largest losses seen among Christians and Buddhists. As the sharp growth of the “nones” in recent years suggests, most disaffiliation has been in the direction of no religion. Most of this disaffiliation has come from those raised Christian. Spain leads the list, with 35 percent of adults saying they were raised Christian but are now religiously disaffiliated. Other countries with large Christian disaffiliation populations include Sweden and Germany (both 29 percent), the Netherlands (28 percent), and Canada and the United Kingdom (26 percent). The United States is in the middle, with 19 percent of adults saying they disaffiliated from Christianity. But nearly all Christians in the 27 majority-Christian countries have retained their religion, especially in the Philippines, Hungary, and Nigeria, where nearly all people who say they were raised Christian are still Christians as adults. In moving the other way toward Christian affiliation, Singapore and South Korea had fairly high rates of entrance into Christianity, with about 4-in-10 or more Christian adults in these countries saying they were raised in another religion or with no religion. In general, the most religious switching is taking place in South Korea (with 50 percent of adults having switched religions), Spain (40 percent), Canada (38 percent), Sweden (37 percent), the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (both 36 percent). The countries with the least religious switching, according to the report, are Tunisia and Bangladesh.

(The Pew Report can be downloaded here: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2025/03/26/around-the-world-many-people-are-leaving-their-childhood-religions/)

- Finland has recently been seen as either a bellwether or an anomaly in research suggesting that its boys are more religious than its girls, but a recent survey finds that the latter are also showing signs of religious interest and belief. As Evangelical Focus newsletter (March 11) reports, Kati Tervo-Niemelä of the University of Eastern Finland, who has led studies of young people preparing for confirmation, previously found that boys in Finland were becoming more committed to Christianity than girls. Since 2019, when the share of young males saying they believed in God was on par with that of young females at 36 percent, the proportion of these boys increased each year to reach 50 percent by 2023. But from more recent 2024 data, Tervo-Niemelä now finds that girls are approaching the levels of boys in religiosity. The new survey shows that 62 percent of boys attending confirmation school now say they believe in God, but the proportion of girls doing so has also risen to half of those preparing for confirmation. This is an increase of 13 percentage points from the previous year.

The researcher said that this change cannot be explained solely by the fact that young people who are not religious are not going to confirmation preparation, because the popularity of confirmation school has remained relatively high and at the same time the number of people declaring themselves believers has risen very significantly. The newsletter also notes that recent surveys in Finland show other curious patterns: young people in cities are more religious than their counterparts in the country—a finding which runs against the long-held position that religiosity is stronger in rural areas. According to recent studies of confirmation preparation, young people in cities are more likely to believe in God and the resurrection of Jesus than those in rural areas. Those who do not believe at all are more numerous in rural areas. According to Henrietta Grönlund of the University of Helsinki, an explanation for this may be that rural areas are more homogeneous in terms of population and religion, while urban areas are more diverse, with different beliefs present.

(Evangelical Focus, https://evangelicalfocus.com/europe/30401/in-finland-signs-of-renewed-interest-in-christianity-among-girls)

- A study on the growth of modern banking and finance in China finds that Protestant missions have had both a historical and contemporary impact on this form of market-based capitalism.Economists Riccardo Di Cato and Jiacheng Li (both at the University of California, San Diego) presented their research at the early-March meeting of the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture (ASREC) in Washington, DC, attended by RW. They looked at the financial effect of missionary expansion by Protestants (mainly Presbyterians) from 1860 to 2022. While there were traditional banks in China before that period, they did not take deposits and relied on personal networks. Using the China Historical Christian Database, the researchers located missions in China and found that they were in the vicinity of modern banks, often in the interior of the country where the missionaries had penetrated, as opposed to the coast where Western traders were located.

Missions played a strong role in educating the Chinese to engage in banking, and missionaries were also pioneers in trading, conducting financial transactions and maintaining information flows with banks back home. There was a high ratio of Christian bankers that increased in places with missions. In that early period—up to 1950, when missionaries were expelled from the country—there were 30 to 50 bankers educated in the Christian schools connected with missions. This effect was driven more by Protestants than Catholics. The missionary-bank effect was less evident after 1950, but could again be seen in the period of liberalization from 1978 into the 2000s, when Christians regained influence in education, fostering trade, spreading new technology, and enacting policies of limited state interference with banks.

- Exposure to political violence drives up religiosity, especially in its communal forms, according to a quasi-experiment by economist Mohammad Isaqzadeh of Chapman University.. In a paper presented at the early-March conference of the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture (ASREC) in Washington, DC, which RW attended, Isaqzadeh reported on his study of 10 violent neighborhoods and 10 nonviolent neighborhoods in Afghanistan that drew a random sample of 1,585 residents in 2020 and 744 in 2021 and used a test-retest method in studying the participants’ exposure to violence. Isaqzadeh also conducted 70 qualitative interviews with residents in these neighborhoods. In studying the effects of participants’ exposure to neighborhood violence, violence against family members, and personal violence, he measured religious devotion both on an individual level (in the forms of listening to Koran readings and following Islamic programs) and communal one (as prayer at mosques). Isaqzadeh found that having family killed or injured did not correlate with increases in personal religiosity, while exposure to personal violence did. Family injury and death did, however, drive up communal religiosity. Isaqzadeh found that personal exposure to political violence is similar to aging 13 years in terms of increasing personal religiosity. Death and anxiety were significant drivers of religiosity, but such factors as receiving aid after exposure to violence and Muslim identity did not have a significant effect.

- Religion can be a strong motivating factor in water conservation policy in the Middle East, a study by economist Giulia Buccione of Stanford University suggests. In a paper presented at the early-March meeting of the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture (ASREC) in Washington, DC, attended by RW, Buccione reported results from an experimental study examining if religion, specifically Islam in this case, can spearhead change in a region known for its water-stressed conditions. The experiment, which took place in Jordan, was based on the fact that water has a special resonance in Islam, being used in such practices as ablution (or washing) before prayer and charity as expressed in providing water for the poor. It was targeted to women leaders, since they are key actors in household water management. The study tested the effect of Islamic religious messaging concerning water by comparing a class receiving this messaging with a control group where no such messaging was given. The experimental treatment included messages about water as a blessing, the sin of wasting water, teaching on ablution, water as an act of charity, as well as secular information on water management. The treatment effect in conserving water was three times larger than the secular approach in the control group. But it was also found that pushing religious norms that were less established, such as using treated water, caused a backlash among the subjects in the experimental group.

- The 2011 Egyptian uprising and its aftermath transformed the religious and spiritual lives of upper-middle-class Egyptians who participated in the revolution, interviews with these participants suggest.In an article published in Cultural Anthropology (February), Amira Mittermaier (University of Toronto) explores the “religious afterlives” of the revolution, focusing on how the experience of the huge gatherings at Tahrir Square (Cairo) led to significant religious transformations among former revolutionaries. The researcher reports that many participants experienced Tahrir Square as not just a political event but a spiritual one, describing it as a place where “God was manifesting” or where they felt “a blanket of light” and the presence of angels. After the revolution, and especially following the 2013 Rabaa massacre (when police and military forces killed more than 800 Muslim Brotherhood supporters), participants engaged in deep theological questioning and spiritual experimentation.

A widespread turn to Sufism emerged among these young, educated Egyptians, often merging with practices like yoga, meditation, and therapy. Many participants rejected their parents’ more rigid, rules-based Islam in favor of a more personal, experiential connection to God, separating “God” from “Islam” as an institution. Mittermaier explains that this post-revolutionary spirituality is not simply secular or the “spiritual-but-not-religious” variety found in Western contexts; it maintains a belief in divine sovereignty while questioning religious authority. The revolution’s religious afterlives continue today, with some participants supporting Palestinian causes through spiritual practices during the Gaza war, showing how seemingly apolitical spiritual practices can retain revolutionary potential. Mittermaier argues that these religious transformations represent a continued form of revolutionary spirit, even as direct political action became impossible under increased authoritarianism. Rather than seeing these spiritual practices as mere retreat or defeat, she interprets them as keeping alive the indeterminacy and experimental spirit of the revolution in unexpected forms.

(Cultural Anthropology, https://journal.culanth.org/index.php/ca)