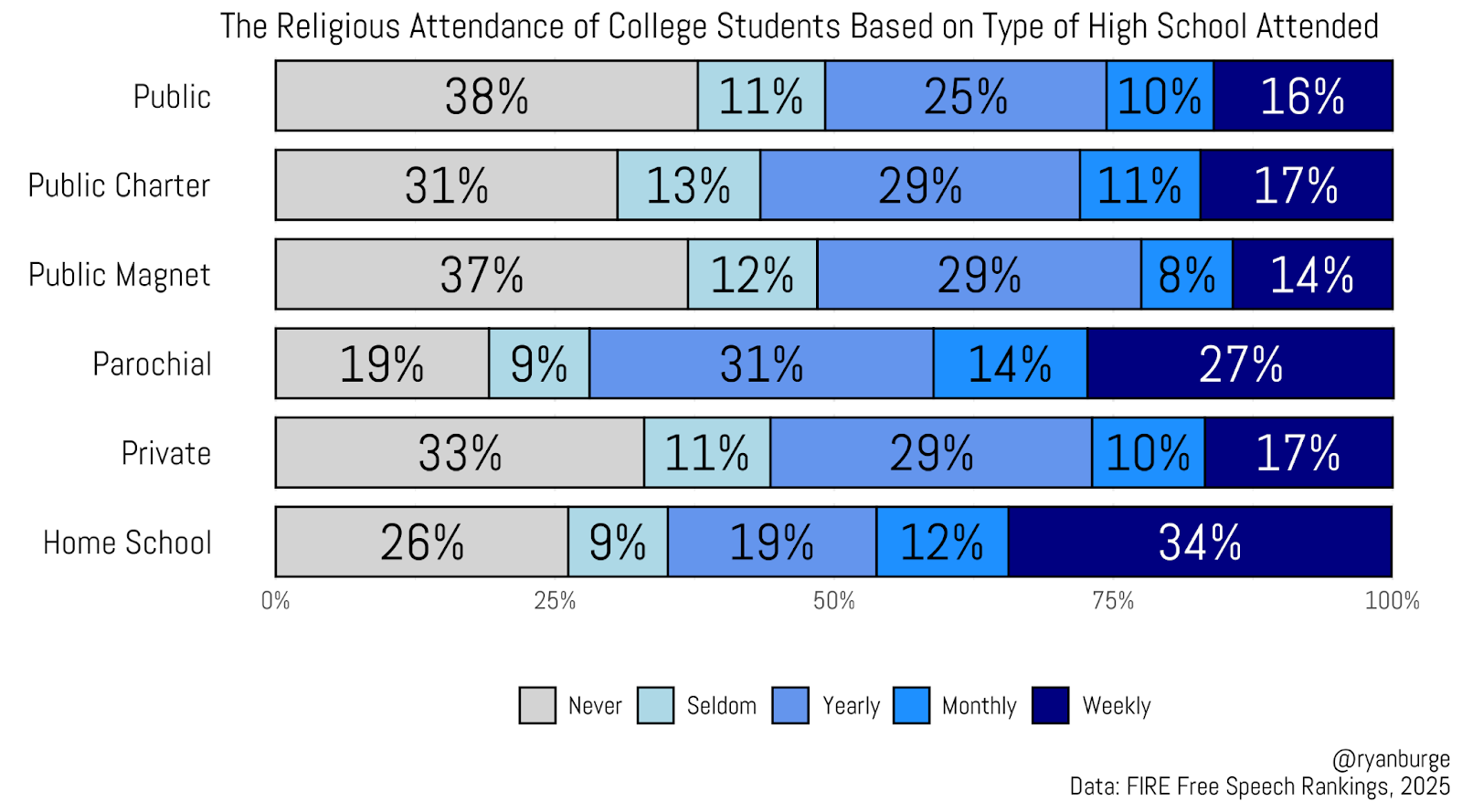

Burge writes that these findings reinforce the stereotype that homeschooled students are more religious and right-leaning, yet ideologically similar to parochial school students. The most left-leaning group is composed of those attending a public magnet school. They were both the most liberal and Democratic-leaning, while private, public, and public charter students were slightly less liberal and less Democratic than those who went to a public magnet school. But these groups were clearly left of center, too. Burge writes that “there are two groups that are off to themselves in the top right of this graph—those who went to parochial school and those who were homeschooled. The parochial school kids were slightly to the left of center on both metrics,” while the homeschooled students were slightly to the right. “But you need to consider the scale of both axes here. These homeschooled kids are almost exactly in the dead center of both of these scales. The average homeschooled respondent was independent when it came to partisanship and middle of the road on political ideology. I don’t see any evidence that they are far right,” Burge concludes. By restricting the sample to Christians, he finds that while public magnet school students are still left of center, the Christian homeschooled are only slightly right of the parochial school student. In other words, homeschooled kids “honestly look a lot like students who went to parochial schools.”

Such support is also linked to a desire to protect the sanctity of the nation’s Christian heritage, while those opposing bringing church and state closer together do so out of a sense that such a union would be unfair. The researchers found that the desire to allow prayer in schools and religious symbols in public spaces was strongest among those with pronounced liberty and sanctity moral foundations. “This likely means that people who favor public religious expression, but not a union of church and state, do so because they see individual religious expression as a sacred national ideal.” Goff, Silver, and Iceland add that “differences over Christian nationalism emerge not because some people care about the harm Christian nationalism could bring to non-Christian Americans, while others don’t. Rather, our findings suggest that those who support Christian nationalism do so because they are more sensitive to violations of loyalty, sanctity and liberty, and less sensitive to violations of fairness.” Even after taking into account variables such as conservatism and race, the salience of these moral foundations remains.

(The Conversation, https://religionnews.com/2025/01/23/research-suggests-moral-foundations-play-a-critical-role-in-attitudes-toward-christian-nationalism/)

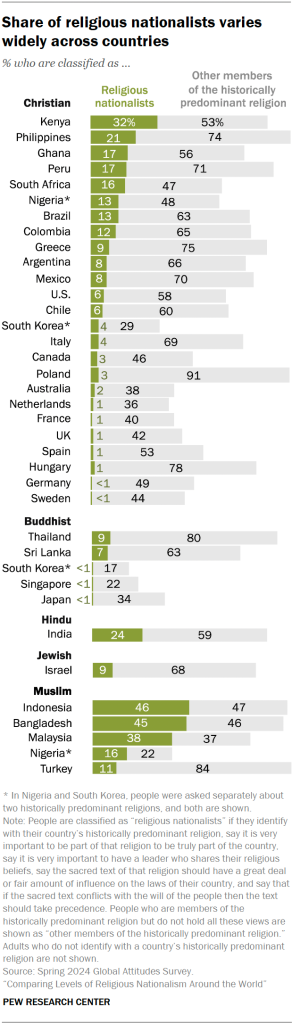

The growth of religious nationalism has been seen worldwide, but its strength varies considerably, with the U.S. showing only a modest Christian nationalist presence, according to a Pew survey. The survey asked respondents similar questions to those asked in other surveys regarding Christian nationalism, such as on the importance of the heritage of a country’s predominant religion, the importance of national leaders sharing religious beliefs, and the influence of a sacred text on laws. The survey found that the prevalence of religious nationalism varies widely across the 35 countries included in the study, with fewer than 1 percent of adults surveyed meeting the criteria in Germany and Sweden, compared with more than four-in-ten in Indonesia (46 percent) and Bangladesh (45 percent). The U.S. “does not stand out for especially high levels of religious nationalism. Just 6 percent of U.S. adults are religious nationalists by the combination of these four measures, about the same level as several other countries surveyed in the Americas, such as Chile (6 percent), Mexico (8 percent)…Argentina (8 percent)…Colombia (12 percent), Brazil (13 percent) and Peru (17 percent).”

But American respondents were more likely than those in any other high-income country surveyed to say the Bible currently has either a great deal or some influence over the laws of their country, or should have such influence. Americans were also among the most likely of any high-income nation to describe a religious identity as very important to truly sharing a national identity, and to say that it’s very important for their country’s political leader to have strong religious beliefs. The survey shows that there is some difference between high-income and middle-income countries on public attitudes about religion. People in middle-income countries are more likely than people in richer countries to say that religion does more good than harm for society, encourages tolerance, and does not support superstitious thinking. People in middle-income countries are also more likely to be religious nationalists. But religious nationalists did not make up a majority of the population in any country surveyed, although in 13 of the 17 middle-income countries, there were double-digit shares of religious nationalists. Religion also played more of a role in national identity in the middle-income countries than the high-income countries. While comparatively few people in most high-income countries said that sharing the country’s historically predominant religion was very important for being “truly” part of that nation, half or more in most middle-income countries saw religion as a key part of national belonging.

(The Pew study can be downloaded here: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2025/01/28/comparing-levels-of-religious-nationalism-around-the-world/)

Although the U.S. is marked by sharp polarization over politics, congregations, both liberal and conservative, tend to avoid politically contentious positions, according to a study by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research. The study, entitled “Politics in the Pews,” is based on surveys of 15,278 congregations conducted as part of the Faith Communities Today project in 2020. The analysis found that nearly half of the congregations actively avoided discussing politics. As reported in Christian Century (February), it found that while 23 percent of congregation leaders did identify their congregations as politically active, only 40 percent of these engaged in “overtly political activities” over a 12-month period. “Political activity” was defined in the study as handing out voting guides, organizing protests, and inviting candidates to address congregations. In almost half of the congregations (45 percent), leaders thought most participants didn’t share the same political views, leading to avoidance of the subject. Against the stereotypes of evangelical congregations’ political activism, the study, led by Scott Thumma and Charissa Mikoski, found that Catholic and Orthodox parishes were actually more engaged than Protestant churches. As is often reported, churches with more than 50 percent black membership were found to be more likely to be political in their activities.

Although the U.S. is marked by sharp polarization over politics, congregations, both liberal and conservative, tend to avoid politically contentious positions, according to a study by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research. The study, entitled “Politics in the Pews,” is based on surveys of 15,278 congregations conducted as part of the Faith Communities Today project in 2020. The analysis found that nearly half of the congregations actively avoided discussing politics. As reported in Christian Century (February), it found that while 23 percent of congregation leaders did identify their congregations as politically active, only 40 percent of these engaged in “overtly political activities” over a 12-month period. “Political activity” was defined in the study as handing out voting guides, organizing protests, and inviting candidates to address congregations. In almost half of the congregations (45 percent), leaders thought most participants didn’t share the same political views, leading to avoidance of the subject. Against the stereotypes of evangelical congregations’ political activism, the study, led by Scott Thumma and Charissa Mikoski, found that Catholic and Orthodox parishes were actually more engaged than Protestant churches. As is often reported, churches with more than 50 percent black membership were found to be more likely to be political in their activities.

(Christian Century, https://www.christiancentury.org/)