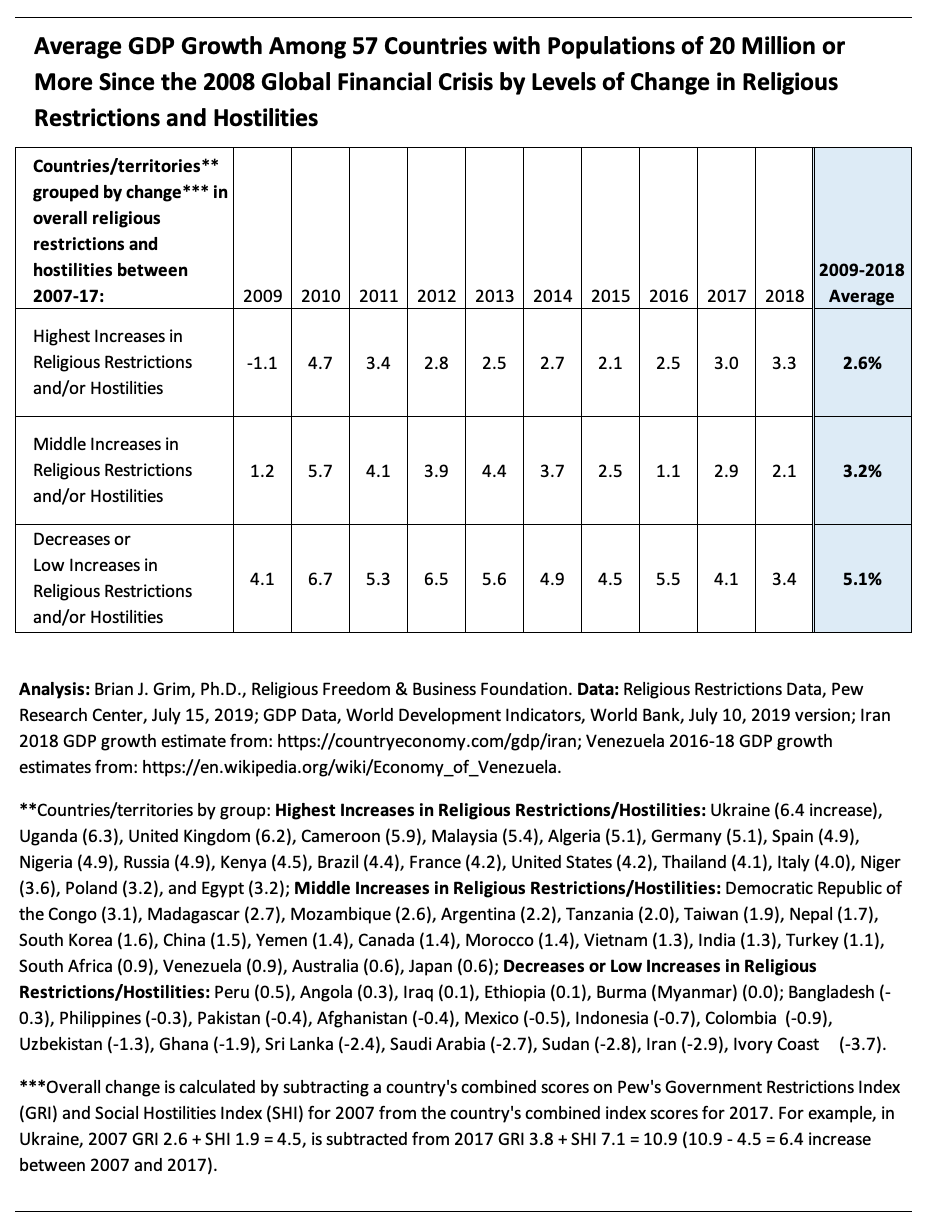

There has been a significant decline in religious freedom from just a decade ago, a trend which may adversely affect economic growth, according to an analysis by the Religious Freedom & Business Foundation (RFBF). A just-released Pew Research study found that governments in 52 out of 198 countries and territories had high or very high restrictions on religion in 2017, up from 40 in 2007. An even larger number of countries (56) had high or very high social hostilities toward specific religious groups within their societies, increasing from 39 in 2007.

The RFBF analysis utilizing this data found that GDP growth in the 19 countries that either reduced or had very low increases in their overall religious restrictions and hostilities averaged 5.1 percent per year between 2009 and 2018. “It is notable that several of the countries in this category had high religious restrictions and hostilities, but even modest decreases in these were associated with economic dividends. Conversely, countries with significant increases in religious restrictions and/or hostilities averaged 2.6 percent annual GDP growth.” China, the world’s second-largest economy, has seen a significant slowdown in its economic growth over the past decade coinciding with its multi-year national campaign to repress religion.

(The RFBF report can be downloaded at: https://religiousfreedomandbusiness.org/2/post/2019/07/economic-growth-slowed-by-dramatic-global-decline-in-religious-freedom.html)

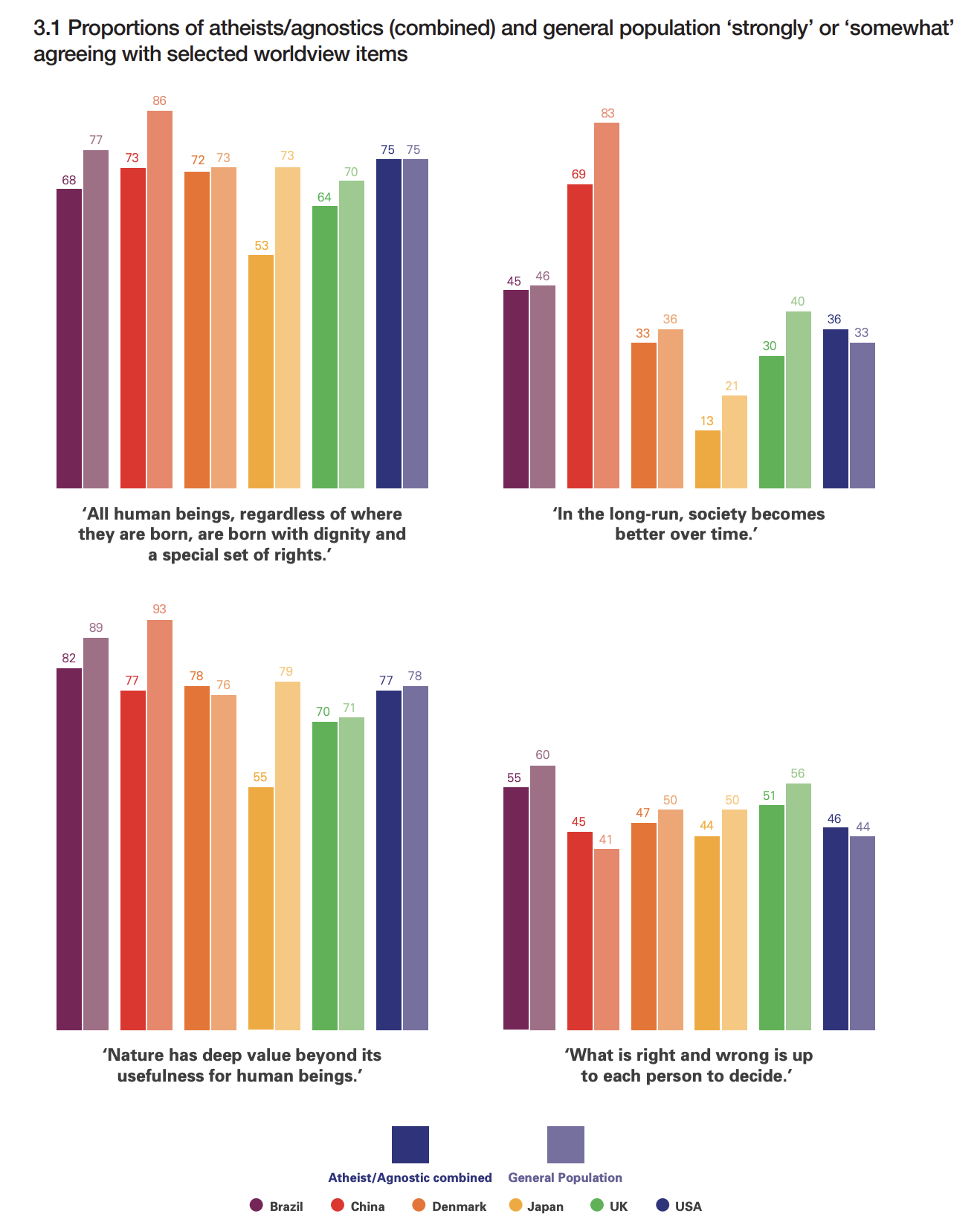

“Understanding Unbelief,” an international study on atheism and other forms of non-religion, recently issued a report on its findings so far, challenging the view that self-identified nonbelievers are always equivalent to atheists. The program, sponsored by the Templeton Foundation, is unique for its international approach, conducting surveys and other research in Japan, Brazil, China, Denmark, the UK, and the U.S. The most recent survey was conducted last April and May, with representative samples of both unbelievers (atheists and agnostics combined) and, for comparative purposes, the general population in each of these six countries. The national context was found to be important for the characteristics of unbelievers: While majorities of unbelievers in all six countries claimed no religious affiliation, in Denmark 28 percent identified as Christian, while in Brazil the figure was 18 percent. Eight percent of unbelievers in Japan identified as Buddhists. Unbelief in God does not necessarily mean not believing in other supernatural forces, with only minorities of atheists and agnostics in each country being “thoroughgoing naturalists.” While atheists and agnostics do tend to believe that the universe is “ultimately meaningless” compared to believers, only a minority of them in each country actually held to this position. The survey also found that atheists and agnostics believe in objective moral values and human dignity at rates similar to the general population.

“Understanding Unbelief,” an international study on atheism and other forms of non-religion, recently issued a report on its findings so far, challenging the view that self-identified nonbelievers are always equivalent to atheists. The program, sponsored by the Templeton Foundation, is unique for its international approach, conducting surveys and other research in Japan, Brazil, China, Denmark, the UK, and the U.S. The most recent survey was conducted last April and May, with representative samples of both unbelievers (atheists and agnostics combined) and, for comparative purposes, the general population in each of these six countries. The national context was found to be important for the characteristics of unbelievers: While majorities of unbelievers in all six countries claimed no religious affiliation, in Denmark 28 percent identified as Christian, while in Brazil the figure was 18 percent. Eight percent of unbelievers in Japan identified as Buddhists. Unbelief in God does not necessarily mean not believing in other supernatural forces, with only minorities of atheists and agnostics in each country being “thoroughgoing naturalists.” While atheists and agnostics do tend to believe that the universe is “ultimately meaningless” compared to believers, only a minority of them in each country actually held to this position. The survey also found that atheists and agnostics believe in objective moral values and human dignity at rates similar to the general population.

(To download this report, visit: https://research.kent.ac.uk/understandingunbelief/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/2019/05/UUReportRome.pdf)

Amid growing negative reactions to immigrants and a growing anti-immigrant and populist movement in Italy, more religious Italians tend to take a less anti-immigrant stance, according to a paper presented at the recent meeting of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion in Barcelona, Spain. Cristiano Vezzoni (University of Milan) looked at data from the European Social Survey and the European Values Survey and found increasingly critical views on immigration among Italians. Immigration went from being the most serious or second most serious issue for four percent of the Italian population in 2014 to 23 percent in 2018. Religious affiliation actually had a negative effect on holding a more inclusive view of immigration. But religious participation was found to have a positive effect on attitudes toward immigrants. “Going to church seems to immunize one from negative attitudes toward immigrants but belonging by itself seems to bring more negative attitudes towards immigrants,” Vezzoni concluded.

Amid growing negative reactions to immigrants and a growing anti-immigrant and populist movement in Italy, more religious Italians tend to take a less anti-immigrant stance, according to a paper presented at the recent meeting of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion in Barcelona, Spain. Cristiano Vezzoni (University of Milan) looked at data from the European Social Survey and the European Values Survey and found increasingly critical views on immigration among Italians. Immigration went from being the most serious or second most serious issue for four percent of the Italian population in 2014 to 23 percent in 2018. Religious affiliation actually had a negative effect on holding a more inclusive view of immigration. But religious participation was found to have a positive effect on attitudes toward immigrants. “Going to church seems to immunize one from negative attitudes toward immigrants but belonging by itself seems to bring more negative attitudes towards immigrants,” Vezzoni concluded.

While institutional religion is declining in Hungary, personal religiosity is growing and tending toward more orthodox beliefs, according to sociologist Gergely Rosta (Pázmány Péter Catholic University, Hungary), who presented a paper at the recent meeting of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion in Barcelona. Hungary has become more secularized than other Eastern European societies, with half of Hungarians claiming to be nonreligious. But accompanying this secularization is an increase in individual forms of religion, including the practice of prayer. There has also been a cohort change, with people who didn’t believe in God earlier now saying they do believe. The study, based on the European Values Survey (2017–18) and European Social Survey (2016), as well as surveys of youth (2016) and Catholic youth (2016), found that, between 2008 and 2018, patterns of religious participation have remained stable, with a slight increase in church attendance. And while the belief in God has remained stable, other beliefs, such as in life after death and in heaven and hell, have increased. In other words, those who believe in God are now more likely to have these related beliefs.

At the same time, the belief in a non-personal God has increased to the same level of prevalence as belief in a personal God. The general belief in God thus increased from nine percent in 2008 to 20 percent in 2018. There has also been an increase in “personal spirituality,” and these increases were found among all generational cohorts. In attempting to explain these changes, some observers have pointed to the growth of religious schools in Hungary, which has been encouraged since 2010 by Christian nationalist Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. But surveys of Catholic youth have found a decline in youth religiosity, such as in the belief in a personal God, and there are also few religion classes offered in these schools. These findings leave open the question of whether these changes show the growth of a “deep religiosity” or whether such beliefs are just external, Rosta concluded.

The growth of nationalism in Hungary and the related drive to restrict immigration, particularly Muslims migrants, have been met with division and uncertainty among Hungarian religious leaders, according to a study presented at the Barcelona meeting of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion in early July. Anna Vancsó (Corvinus University, Hungary) conducted interviews with religious leaders in Hungary between 2015 and 2017 and found that they tended to want to speak only as individuals rather than as representatives of their religious groups on matters of immigration and the rights of Muslims. She found a strong degree of polarization on these issues. Among Catholic and Reformed bishops, there were those who were outspoken on issues of immigration, but few engaged in church-wide attempts to address these concerns, although the Reformed Church has trained migration experts and developed the tools and networks to assist migrants. The smaller churches appear more united on immigration, with some evangelicals, such as the large Pentecostal Faith Church movement, shifting from a more liberal position in the 1990s to support of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and his immigration policies. Two of the three Jewish groups in the country are the most strongly opposed to Orbán and his immigration laws. Vancsó concluded that religious organizations mainly function in a reactive mode and are not “well-integrated into society…to shape” people’s understandings on faith and social issues.

Polish migrants to Ireland show declining religious devotion in their newly adopted country, according to a study presented at the recent conference of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion. The study, presented by Wojciech Sadlon of the Institute for Catholic Church Statistics in Poland, was based on a longitudinal survey of practicing Catholics in Dublin and Galway, focus groups in Dublin and Cork, as well as in-depth interviews. On first impression, Irish census data do not show a great drop in religious faith among Polish migrants, with 34 percent saying it remained the same, 18.4 percent saying it declined, and 7.3 percent saying it increased. But in asking about religious practice, the study found that while 18 percent attended Mass in Poland, only nine percent did so in Ireland. The proportion of those reporting maintaining other religious practices went from 50 percent in Poland to 32 percent in Ireland; participation in prayer groups went from 10 percent in Poland to five percent in Ireland; and while nine percent reported volunteering in Poland, only three percent did so in Ireland.

Polish migrants to Ireland show declining religious devotion in their newly adopted country, according to a study presented at the recent conference of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion. The study, presented by Wojciech Sadlon of the Institute for Catholic Church Statistics in Poland, was based on a longitudinal survey of practicing Catholics in Dublin and Galway, focus groups in Dublin and Cork, as well as in-depth interviews. On first impression, Irish census data do not show a great drop in religious faith among Polish migrants, with 34 percent saying it remained the same, 18.4 percent saying it declined, and 7.3 percent saying it increased. But in asking about religious practice, the study found that while 18 percent attended Mass in Poland, only nine percent did so in Ireland. The proportion of those reporting maintaining other religious practices went from 50 percent in Poland to 32 percent in Ireland; participation in prayer groups went from 10 percent in Poland to five percent in Ireland; and while nine percent reported volunteering in Poland, only three percent did so in Ireland.

The paper reported a tendency among the migrants—many of whom are younger Poles— to see the church in Poland as oppressive while seeing the Irish church as easygoing. Most of the Catholic migrants have adapted to the Irish church, with only 24 percent praying in Polish, even if they are distanced from Irish Catholicism. Thirty-four percent still go to Poland to baptize their children, although first communions tend to be celebrated in Ireland. Sadlon concludes that the declining religiosity of the Polish migrants actually has Polish roots, being linked back to the younger generations’ alienation from the church after 1979. The young migrants’ search for “well-being” makes for an easy adaptation to the more liberal Catholicism of an increasingly secular Ireland.

The idea that Australia is a “Christian nation” is increasingly prominent in political discourse and in the platforms of conservative parties, according to a study by political scientist Marion Maddox (Macquarie University). Maddox, who presented a paper at a conference of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion, meeting in Barcelona in early July, noted that while most indicators show a decline in Christian affiliation, belief and practice among Australians, the use of language referring to Australia as a “Christian nation” has increased since the 1990s. In conducting a textual analysis of the public record of parliamentary debates, Maddox found that mention of the idea of Australia as a Christian nation reached an all-time high during the 1950s (20 mentions) and then fell away until the 1990s, making a comeback particularly in recent years, being raised 11 times in debate since 2011. The platforms of three political parties represented in federal parliament invoke either the idea that Australia is a Christian nation or that it was founded on “Christian principles.” While mentions of Christian nationhood were previously often related to the view that Australia should be more compassionate toward the poor or embrace social justice, the more recent references relate to campaigns to limit immigration, particularly of Muslims.

The idea that Australia is a “Christian nation” is increasingly prominent in political discourse and in the platforms of conservative parties, according to a study by political scientist Marion Maddox (Macquarie University). Maddox, who presented a paper at a conference of the International Society for the Sociology of Religion, meeting in Barcelona in early July, noted that while most indicators show a decline in Christian affiliation, belief and practice among Australians, the use of language referring to Australia as a “Christian nation” has increased since the 1990s. In conducting a textual analysis of the public record of parliamentary debates, Maddox found that mention of the idea of Australia as a Christian nation reached an all-time high during the 1950s (20 mentions) and then fell away until the 1990s, making a comeback particularly in recent years, being raised 11 times in debate since 2011. The platforms of three political parties represented in federal parliament invoke either the idea that Australia is a Christian nation or that it was founded on “Christian principles.” While mentions of Christian nationhood were previously often related to the view that Australia should be more compassionate toward the poor or embrace social justice, the more recent references relate to campaigns to limit immigration, particularly of Muslims.