The religious group with the highest proportion of heterosexuals was Muslims (85 percent), followed closely by Protestants, Catholics, “Just Christians,” and Hindus. Burge was surprised that only 78 percent of Latter-day Saints in college said that they were straight—7 points lower than Protestants. Additionally, 13 percent of LDS students said that they fell into the “something else” camp. The groups that were the least likely to say that they were heterosexual were atheists, at 55 percent, and agnostics, at 53 percent; those who said that they were “nothing in particular” were only at 62 percent. As for transgender issues, just 1 in 100 Christians said that they were not a man or a woman, and even more secular and liberal groups including atheists and agnostics identified largely as man/woman (97 percent of each group).

(Get Religion, https://www.getreligion.org/getreligion/2023/9/19/gender-sexual-orientation-and-religion-among-american-college-students)

Source: Rawpixel.

There was also an increase in the number of congregations in the RCMS from 2010 to 2020, 4.2 percent, with a population growth of 5.3 percent. “This implies that the congregations we are finding in our survey are likely uncounted because they are the product of migration. A natural birthrate increase would not yield immediate affiliation and establishment of additional religious congregations within a 10-year time period,” the authors observe. Thus these uncounted churches are those that the RCMS would have difficulty collecting data on—Latino and other ethnic churches and non-denominational and megachurch plants. Melton, Foertsch, and Ferguson conclude that the fact that more than 23 percent of the congregations in these areas were not reported in the RCMS data suggests that religious demographers are missing a “new invisible community” of non-denominational and independent congregations elsewhere. This is consistent “with what is known about religious life in America as a whole—that both total church/religious membership and the number of denominational/religious bodies has been on a 200-year growth trajectory that continues to the present.”

(Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14685906)

Source: BoxCast.

The original converts in Kitigan Zibi are no longer alive, a fact that leads Simard-Emond to urge Canadian and American scholars not to lose time in exploring the significant presence of Witnesses in indigenous communities. In the United States, there are a number of Jehovah’s Witnesses among Navajos, said to have been the first native nation to have established a congregation using their own language. In Canada, there have been Witnesses in aboriginal communities at least from the 1930s in British Columbia. But research on the JWs among indigenous people remains extremely scarce.

(Social Compass, https://journals.sagepub.com/home/SCP)

Jehovah’s Witnesses at the “Gateway to NaWons” event in June 2015 (source: Jehovah’s Witnesses).

(Juicy Ecumenism, https://juicyecumenism.com/2023/09/14/dc-mainline/?fbclid=IwAR1ocyGMOir77Q5b-4FoJjzIPSf4pqNuhcVlTfkh9Hx_nuaeJOYxacV1LNc)

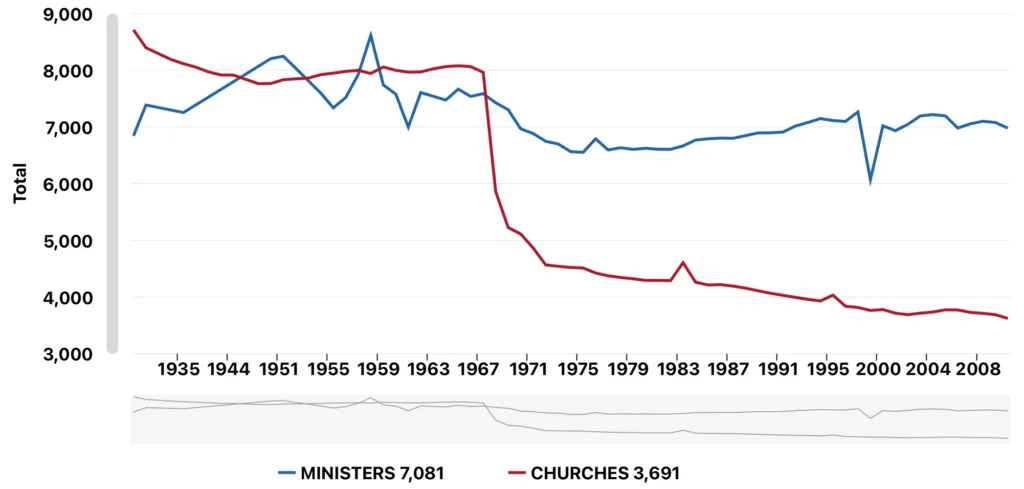

Source: National Council of Churches’ Historic Archive CD and print editions of the Council’s Yearbook of American and Canadian Churches.

(Mobilization, https://mobilization.sdsu.edu/)

Source: Michigan Publishing (University of Michigan).

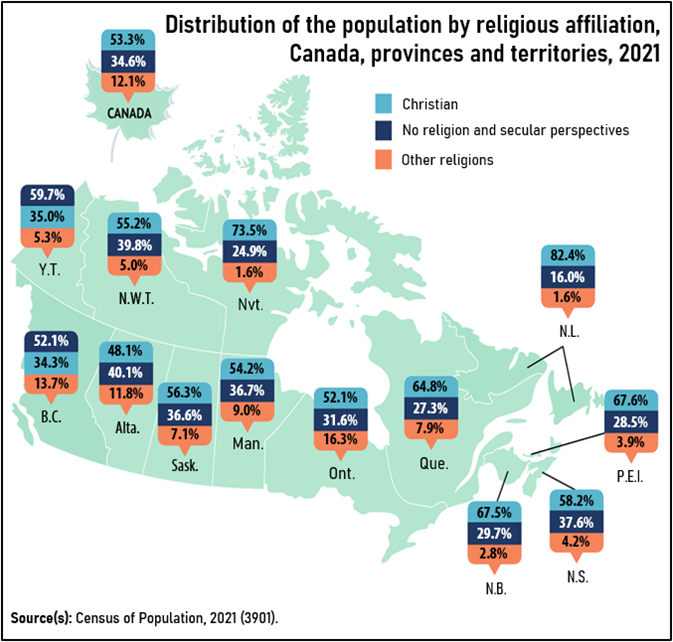

Going to the far east of the country, in Atlantic Canada (such as New Brunswick and Newfoundland) organized Christianity is still the norm and nones experience more stigma in disaffiliating, but many still retain some beliefs and some pray occasionally. In the western prairie provinces (such as Alberta and Manitoba), there are also remnants of belief and practice, but there is also a higher rate of agnosticism among nones there. In Ontario, nones have a higher rate of uncertainty and disinterest when it comes to belief systems and worldviews and have the highest rate of infrequent attendance at religious services. Quebec, in contrast, has the highest rate of polarization of nones in Canada between more anti-religious atheists and those who practice “many self-identified spiritual practices.” Wilkins-Laflamme concludes that the different positions that Canadian nones take toward spirituality and religion complicates the picture of a widespread movement toward secularism in the country.

(Studies in Religion, https://journals.sagepub.com/home/sir)

(Future First, www.brierleyconsultancy.com)

Christian Brethren Assembly in Tamil Nadu, India (source: JustDial).