Source: Religion in Public.

Source: Communio.

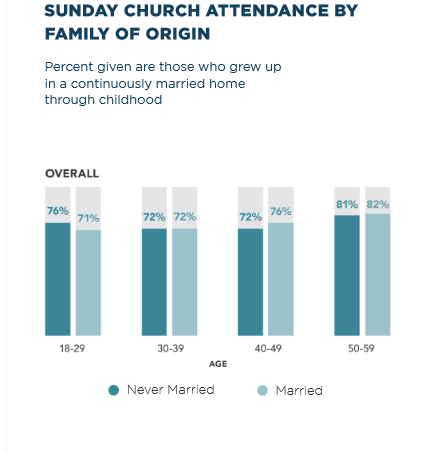

Just 15 percent of married people in church considered themselves lonely while more than 50 percent of all singles did so, with the higher loneliness reported not among widows, but among never-married men and women between the ages of 30 and 39. The survey also found that about one in five married churchgoers struggled in their marriage. “The gap in relationship satisfaction between married men and women is substantial as women are 62 percent more likely to report struggling than married men,” according to the study’s report. When compared to those who were married, “cohabiting church goers were substantially more likely to report struggling in their relationship. Cohabiting women were 76 percent more likely to struggle than married women and 85 percent more likely to struggle than a cohabiting man. Both cohabiting men and women were far more likely to report being lonely than married men and women.” In sum, a respondent’s family of origin remains an exogenous factor in faith that is not affected by the control variables of changing attitudes or opinions. In other words, the structure of a person’s childhood home is shown to precede in time and place any adult decision to attend church. The researchers conclude that “Causation is notoriously difficult to prove. However, the overall homogeneity in the families of origin from church goers in various generations (Gen Z all the way through the youngest Baby Boomers) is striking. The absence of a proportionate number of church attendees who grew up in homes without married parents across all recent generations suggests movement in family structure is at the heart of the decline in church participation.”

(The study can be downloaded at: https://communio.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Final-Study-1.9.pdf)

Source: United Methodist Insight.

A study on clergy leaving their pulpits finds that they are low in number and that those who do leave do so less out of a loss of faith in God and more due to emotional problems and doubts. The study, presented at the late-August meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion in Philadelphia, which RW attended, was conducted by Landon Schnabel of Cornell University.Using data from the National Study of Religious Leadership (2018–2020), Schnabel found that 77 percent of the 1,600 respondents were “very satisfied” with their ministries. Very few (2 percent) often consider leaving the ministry, with 60 percent saying they never consider that option and 30 percent having only thought of leaving once. Although it has been claimed that rising atheism is a factor in clergy dissatisfaction and departures, very few such clergy were found in the survey. But it was found that many clergy (54 percent) have considered other religious-related work outside of the pastorate. Congregational pay and even politics were not significant factors in clergy leaving their churches, but women and younger clergy were more likely to leave. Overall, mental health problems from stress and doubt were the two largest factors in church departures.

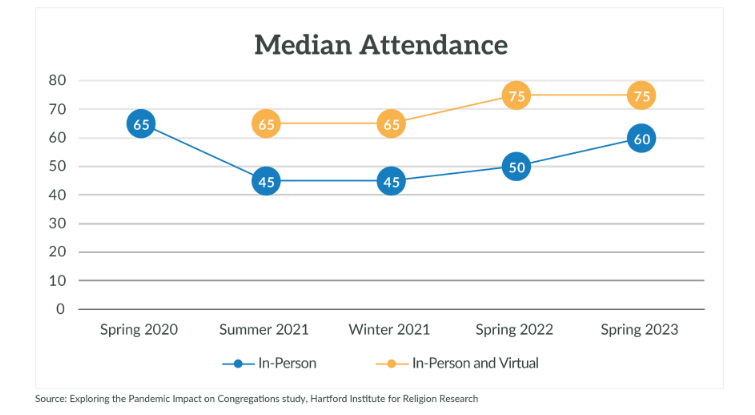

(The Hartford study can be downloaded from: covidreligionresearch.org)

Source: World Religion News.

(Politics and Religion, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-religion)

Source: T4G.

Atheist protestors (source: Chilean Atheist Society).

(Contemporary Jewry, https://www.springer.com/journal/12397)

Synagogue in Capetown (source: University of Cape Town).

Zoroastrian temple in Iran (source: Wikimedia Commons).