- The new, recently released Faith Communities Today (FACT) study shows continuing declines in congregational attendance, although about one-third of congregations report growth. The survey, which was conducted right before the pandemic and is issued every five years, was based on questions about congregational life sent to 15,278 congregations and their leaders from 80 denominations. The survey found that prior to the pandemic, many congregations were small and getting smaller, while the largest ones were finding growing attendance. Another major finding was that congregations have continued to diversify, particularly in terms of racial composition. The first FACT survey in 2000 had found that 12 percent of congregations could be considered multiracial (having either racial majorities of no more than 80 percent or no racial majority); today, 25 percent of congregations can be considered multiracial. Other findings showed a significant increased use of technology, even pre-pandemic. The fiscal health of congregations was found to have remained mostly steady.

(The FACT survey can be downloaded at: https://faithcommunitiestoday.org/fact-2020-survey/)

- A study finds nondenominational churches continuing their growth trajectory even as they now outpace denominational evangelical congregations on such key measures as attendance, youthfulness, diversity, and outreach. The research, based on a random sample of 500 churches, was presented at the late-October meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in Portland, Ore., which RW attended, and is part of the Faith Communities Today (FACT) study that has been conducted by Scott Thumma every five years since 2010. Thumma found that more nondenominational churches in the survey had grown by 5 percent or more than had those associated with evangelical denominations, “and many of them by 25 percent or more over the past 5 years.” He confirmed the recency of a significant portion of nondenominational churches’ founding, with a median founding date of 1970 compared to 1958 for evangelical denominational churches, as independent churches have exited their denominations in the last two decades over such issues as LGBT conflicts.

As observed in previous surveys, most of these nondenominational congregations were found to be involved in formal and informal networks with other congregations, such as ACTS 29 and the Willow Creek Association. Although a relatively recent phenomenon, nondenominational churches tend to show more intentional diversity, greater use of contemporary worship, more fervent religious practices, and more effective member engagement compared to evangelical denominational congregations. Thumma concluded that “one has to wonder if indeed the nondenominational phenomenon isn’t the next wave that supercedes the current more denominationally-based evangelicalism. This is especially true since evangelical denominations have become associated with Trump, anti-vaxers, and Christian Nationalism—while much of the culture is moving in the opposite direction.”

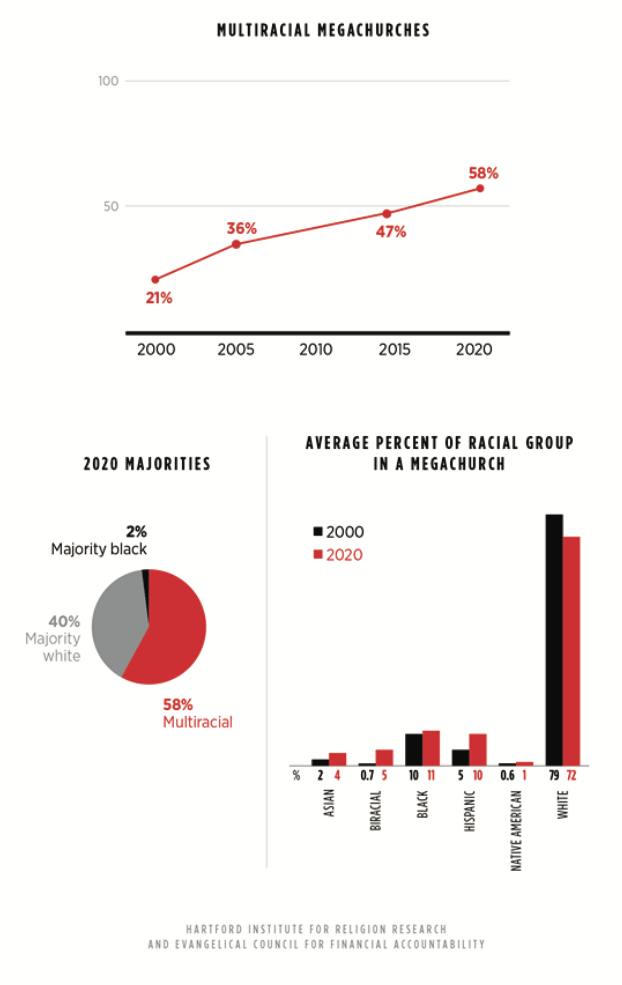

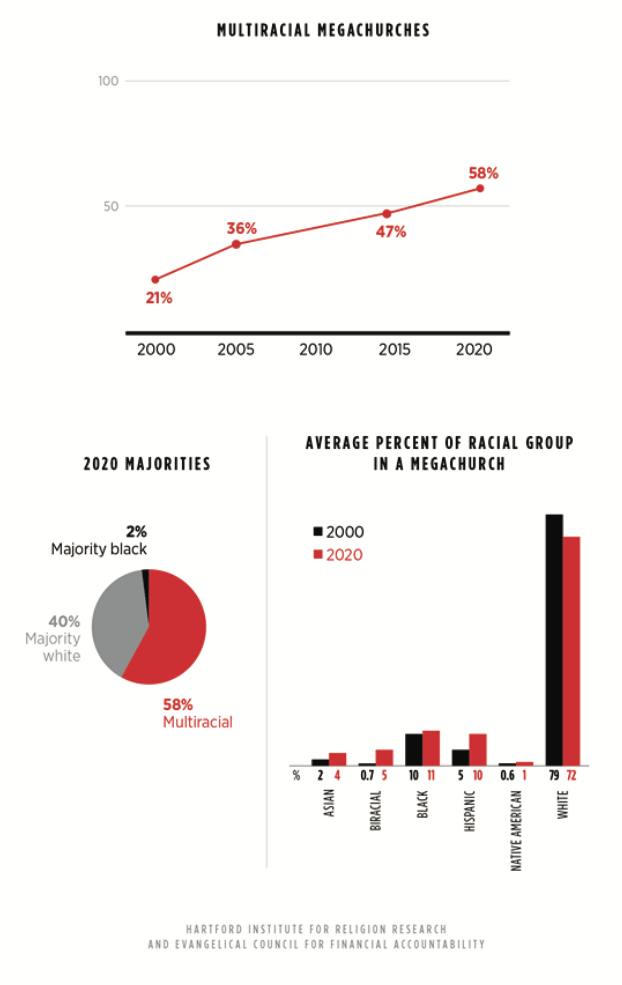

- Although the pandemic is likely to change some aspects of megachurches, the most recent survey of these large and multifaceted congregations finds trends of increasing multiethnicity and continued growth. Sponsored by Evangelicals for Financial Accountability, the Hartford Institute for Religious Research, and Leadership Network, the survey of 582 megachurches was conducted by Scott Thumma and Warren Bird, who presented results at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, which RW attended. The survey found that these congregations’ attendance has continued to rise, even though their seating capacity has remained steady at 1,200. And while two decades ago only 21 percent of megachurches were multiracial (defined as having 20 percent or more of a minority presence), the researchers found that today more than half (58 percent) of these congregations report being so.

The increased racial diversity is accompanied by characteristics that include being better at welcoming and including newcomers and having a greater percentage of immigrants. Three- quarters of the congregations reported growth over the past five years, showing a median growth from 3,800 attenders in 2015 to 4,200 in 2020. Megachurches have also grown in other ways, displaying more involvement in church planting and an increase in the number of multisite campuses (or satellite churches). Bird concluded that the pandemic’s effect on megachurches (on which Thumma is currently leading a large study) will likely sort out these congregations, with those pastors having a “church planter mentality” gaining the advantage as they “replant and relaunch” their ministries. “There will be fewer slots [for megachurches]…but congregations that emerge [from the pandemic] are going to be larger,” he said.

- A national study of religious leaders finds as many continuities as changes in their demographic patterns, morale, and beliefs, according to sociologist Mark Chaves. The study, conducted between 2019 and 2020 among 1,600 religious leaders (both clergy and those in congregational leadership), and presented at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, found that many patterns have held constant since a similar study that was conducted in 2016: clergy were just as likely to be married and showed similar education levels and a similar likelihood of entering the ministry as a second career. As for morale, while few have left the clergy for secular work, the study does show that the proportion of those considering leaving the ministry has increased from five percent in 2016 to nine percent today. Clergy have definitely aged, with those 44 years old and younger having made up 27 percent of the clergy studied in 2016, compared to only 12 percent today.Clergy were found to be less white, more female, more likely to have another job (36 percent today versus 26 percent in 2016), and more likely to work part-time in ministry (29 percent today versus only nine percent in 2016). As for beliefs, the study found mainline church leaders continuing to drift away from their evangelical and Catholic counterparts in their lack of certainty on core beliefs, such as the belief in life after death, with 71 percent holding this belief with certainty compared to 96 percent of other Christian leaders. On politics, the majority of religious leaders showed some political activity and engagement in “cue-giving,” or indirect expression of political views, but mainline leaders were more likely to engage in direct political action than evangelicals. On voting behavior, the study found that clergy were more likely to vote than other adult Americans, with 94 percent saying they had voted.

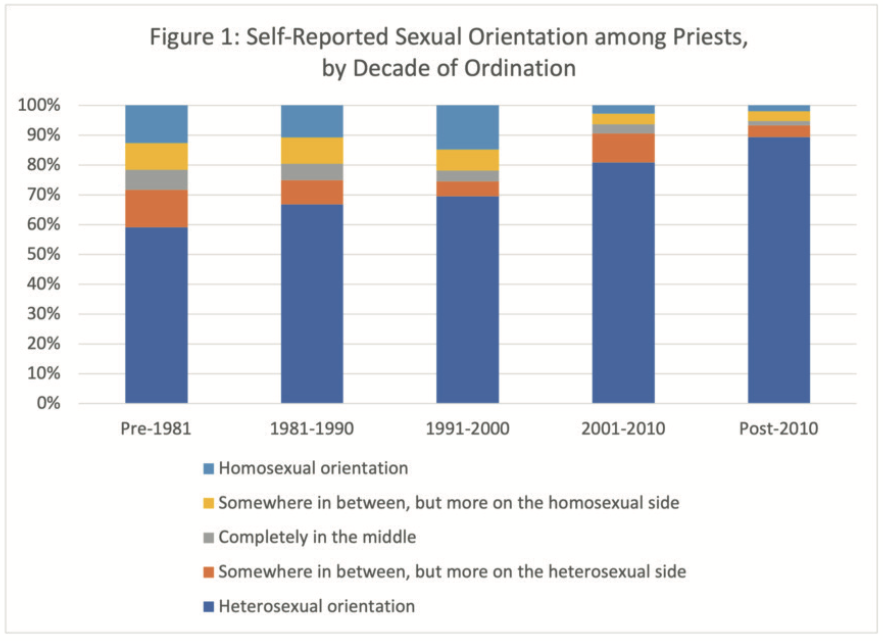

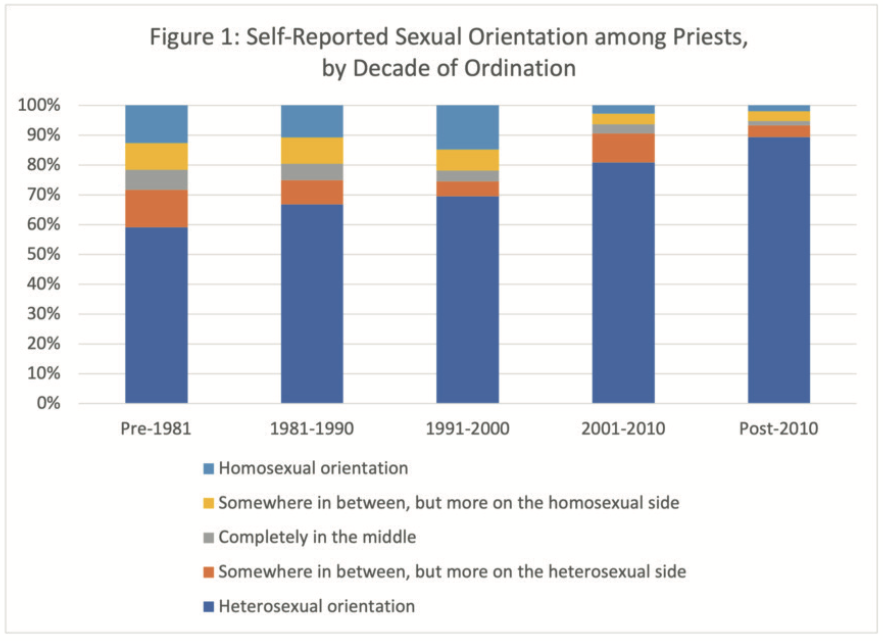

- American Catholic priests have taken a significant conservative turn on their vows of celibacy as well as other sexual matters, according to a 2021 survey cited in the online magazine Public Discourse (October 31). Conducted in late 2020 and early 2021, the Austin Institute fielded a survey replicating a variety of questions that were posed to American priests in 2002 by the Los Angeles Times. The survey was conducted among just over 1,000 priests, who were not randomly sampled but drawn from the extensive lists in the Official Catholic Directory (which the LA Times also used), as well as the mailing list of a large Catholic nonprofit organization. The survey found that a self-identified homosexual orientation was notably more common among ordinations that occurred before the year 2000 (between 11 and 15 percent) than it was after (2–3 percent). A heterosexual orientation appeared to be a linear function of the date of ordination, ranging from 59 percent of pre-1980 ordinations to 89 percent of those priests ordained after 2010. At this rate, it is projected that by 2041 the share of Catholic priests self- identifying as either entirely or mostly heterosexual should amount to over 92 percent, while those self-identifying as either entirely or mostly homosexual should make up 7 percent.As for celibacy, the questions posed in the 2002 LA Times survey about this issue, and replicated in 2021, resulted in less of a trendline among ordination cohorts. But the statement, “Celibacy is not a problem for me and I do not waver in my vow,” was chosen by fewer respondents before 2001 than it was after, with 55 percent of priests ordained on or after that year choosing it. Among priests ordained before 2000, the most frequent responses to a question about the value of celibacy to their priesthood were that it “takes time to achieve” and “it is a journey.” After 2000, the modal answer shifted to one of greater confidence and commitment, and even more so after 2010. But the attitude shift on homosexuality is the most noteworthy. Among priests ordained before 1981, only 34 percent responded “always” to the question of whether homosexual behavior was sinful, with an additional 33 percent saying “often.” The “always” answer grows in a linear fashion up through the most recent cohort: 45 percent (1981–1990), 57 percent (1991–2000), 82 percent (2001–2010), and finally 89 percent among those ordained after 2010.

(The Public Discourse, https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2021/10/78773/)

- According to a recent study, the events of January 6 leading to the riot at the Capitol building in Washington were in part driven by a form of Christian nationalism fed by conspiratorial thinking, white identity concerns, and political grievance. The study, conducted by David Buckley, Adam Enders, and Miles Armaly, and presented at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion, used a survey of 817 respondents, whose demographic traits were matched with those of the general population according to the U.S. Census. Even though its definition is contested, attention to “Christian nationalism” has grown since the Trump presidency, and generally it has come to refer to those Americans supporting the Christian nature of the U.S., including its government. Buckley, Enders, and Armaly found that those supporting the January 6 riot had sympathy for Christian nationalist views, but that when there were low levels of white identity, perceived victimhood, and QAnon conspiracy support, the Christian nationalist element was not a significant predictor of such support for violence. The researchers argue that the “strength of the relationship between Christian nationalism and support for violence––in the case of the Capitol riot and more abstractly––is conditional on the strength of one’s identification with the white race, the extent to which one feels like a victim, and strength of QAnon support.”

- A study of rural public religion finds a shrinking of the civic role of religious institutions and a growth of their political dimensions, which adds to polarization. The study, conducted by Penn State University sociologist Gary Adler, was based on 200 interviews with religious leaders across eight sites in Maine and Pennsylvania, and the results were compared to data from the 1998 and 2018 National Congregational Studies. Adler’s paper was presented at the late- October meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in Portland, Oregon, which RW attended. The researcher found that the civic role of public religion in small towns has been decreasing due to related losses and aging taking place in mainline Protestantism. This decline has involved looser connections between religious leaders and congregations and local officials, a high rate (40 percent) of congregations having outside groups use their buildings, and reduced resources as congregations seek to avoid duplication of ministries and outreach programs.

At the same time, a political form of public religion has been gaining ground. Adler sees this in the frequency of voter guides and selective visits made by political candidates. Most of the political influence operates informally, based on conversations, and is most often found in evangelical and Catholic congregations, according to Adler. He adds that the symbolic dimension of public religion is shifting from an inclusive to more particularistic modality, which can be seen in chaplains at various institutions invoking the name of Jesus at public events. The study concludes that as the political form of public religion becomes more prominent, “its civic and symbolic dimensions weaken.”

- The pandemic has accentuated existing differences between the Amish and the Mennonites, with the former showing greater dissent from public health measures as well as higher mortality rates, according to research presented at the recent meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion in Portland. Sara Guthrie, Katie Corcoran and Rachel Stein of West Virginia University examined the responses to Covid of 334 Amish and Mennonite communities in Ohio and Pennsylvania through an analysis of their service announcements appearing in The Budget, a national newspaper of these religious communities. The key difference they found was in the higher proportion of Amish congregations (which are in members’ households) holding in-person services during the peak of the pandemic (78 percent) compared to Mennonite congregations (59 percent). Mennonites were more likely to cancel services during outbreaks (66 percent versus 37 percent for Amish). Amish congregations did follow guidelines for social distancing (with 80 percent implementing social distancing), yet by not canceling services, the virus spread more widely among members.

In another paper in this session, Rachel Stein looked at Amish death rates through an analysis of what are called “excess deaths” in these communities, which capture direct and indirect deaths related to Covid. At the beginning of the pandemic, many observers claimed that Amish communities had more protection from the virus than the rest of the country because of their isolation and lifestyles—a view that Stein sought to test. She collected obituaries appearing in The Budget from 2015 to 2020, drawing on a national sample of 2,400 death notices. By comparing 2020 death rates to the average, she found that excess deaths rose in April, May, and June, and then declined until November when they rose again. The number of deaths in 2020 was higher than the average, and the pattern of Amish deaths was similar to the death rates in the broader society and in Ohio (where many of these Amish lived). As state guidelines were lifted, Amish church life went back to normal, a pattern which still continues, even though there have been new spikes in infections among the Amish, especially since many are not getting the vaccines. Stein concludes that public health publicity has not been effective among the Amish and that such efforts need to incorporate the culture and beliefs of the communities that they are addressing.

- Forty-nine percent of the population of Quebec no longer believes in God, and even 51 percent if only the French-speaking population is considered, according to the daily newspaper Le Devoir (Oct. 22), which commissioned a survey by leading market research institute Leger. While surveys are not an exact science and different surveys may bring partly different results, this one seems to confirm a trend. Compared to previous surveys conducted over the past two decades, it suggests that a decline is continuing. In 2005, 77 percent of the population of Quebec was still claiming to believe in God, according to the Crop Survey Institute, but this was down to 62 percent by 2016. Earlier dubbed a “priest-ridden province,” Quebec has seen drastic changes and is now the least believing region of Canada. According to sociologist Martin Meunier (University of Ottawa), the higher percentage of non-believers in Quebec as compared to the rest of Canada might be partly related to the higher percentage of first- and second-generation migrants in the other provinces.

Meunier notes that during and after what is called the “quiet revolution” in Quebec, from 1960 to the early 2000s, cultural Catholicism still left its mark on the province, with about 75 percent of the children born in Quebec in 2001 being baptized despite a low level of religious practice. Cultural Catholicism is still real for a significant part of the population, but the percentage of newborn children who get baptized has fallen by half. However, Meunier points to the strong variations existing across areas within Quebec beyond the city of Montreal. For instance, in the Diocese of Chicoutimi, more than 90 percent of the people still describe themselves as Catholics. Moreover, evangelical groups have developed in suburbs. Interviews with people who do not believe in God show that this is not necessarily associated with hostility against religion or lack of interest in it. Beyond belief in God, a key issue might be the extent of cultural Catholicism’s ability to persist in some ways. Meunier points out that 73 percent of the people in Quebec still identified as Catholics at the time of the 2011 census. With the results of the 2021 census arriving soon, one can be sure that the level of self-identification will have declined, but it remains to be seen how far.(The Crop blog article reporting on the 2016 survey is available at: https://www.crop.ca/fr/blog/ 2017/168/)