![]() Conflict is growing in congregations as they deliberate on plans to reopen during the pandemic, even as a majority of religious believers and the public tend to accept social distancing rules for all organizations, according to recent studies. A July survey by Lifeway Research found that 27 percent of evangelical and mainline pastors cited addressing complaints and conflict and keeping unity in their congregations as the pressure points they are most strongly feeling. In an April survey, just eight percent cited conflict and disagreement as significant issues (most congregations had discontinued services during that time). Much of the conflicts and division regarding reopening reflect the polarization in the wider society, with some pastors commenting that where there was unity on common beliefs before the pandemic, they now see more political division.

Conflict is growing in congregations as they deliberate on plans to reopen during the pandemic, even as a majority of religious believers and the public tend to accept social distancing rules for all organizations, according to recent studies. A July survey by Lifeway Research found that 27 percent of evangelical and mainline pastors cited addressing complaints and conflict and keeping unity in their congregations as the pressure points they are most strongly feeling. In an April survey, just eight percent cited conflict and disagreement as significant issues (most congregations had discontinued services during that time). Much of the conflicts and division regarding reopening reflect the polarization in the wider society, with some pastors commenting that where there was unity on common beliefs before the pandemic, they now see more political division.

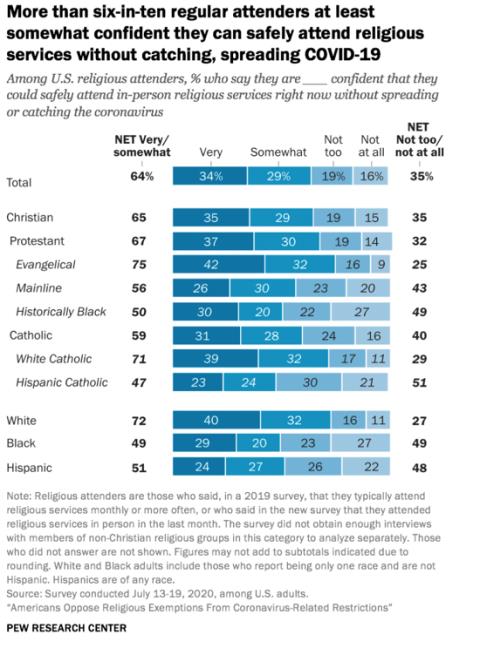

Yet a Pew Research Center survey finds that Americans overwhelmingly say houses of worship should follow the same rules about social distancing and large gatherings as any other organizations or  businesses in their local area. This position was taken by 79 percent of respondents while only 19 percent say that congregations should be given more flexibility than other groups in following social distancing rules. The majority of respondents are in line with recent Supreme Court rulings on this issue. Among U.S. Christians, about three-quarters say churches should be subject to the same rules as other groups, with evangelicals expressing the most support for giving more flexibility to churches. While Democrats were most likely to support social distancing rules applied to all groups, two-thirds of Republicans also agreed on this issue.

businesses in their local area. This position was taken by 79 percent of respondents while only 19 percent say that congregations should be given more flexibility than other groups in following social distancing rules. The majority of respondents are in line with recent Supreme Court rulings on this issue. Among U.S. Christians, about three-quarters say churches should be subject to the same rules as other groups, with evangelicals expressing the most support for giving more flexibility to churches. While Democrats were most likely to support social distancing rules applied to all groups, two-thirds of Republicans also agreed on this issue.

The resistance to the health measures and policies and other incautious health behaviors surrounding COVID-19 among American conservatives is driven more by politicized ideology than by religious motivations and commitment, according to a study in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (online in August 2020). Sociologists Samuel Perry, Joshua Grubbs, and Andrew Whitehead use data from the Public and Discourse Ethics Study, which surveyed 2,519 people and was conducted in 2019 and then later in 2020 during the pandemic. They find that religious commitment, once political ideology is accounted for, tended to move people toward more health-conscious practices, such as washing of hands, wearing masks, and not touching one’s face, during the pandemic. The espousal of conservative ideology and also what the authors call “Christian nationalism” was the leading predictors of Americans engaging in incautious behaviors, including eating in restaurants, visiting friends and family, and gathering in groups of more than 10 people. The authors argue that their conception of Christian nationalism moves people toward incautious behavior through beliefs in divine protection, distrust of scientists and the news media, and devotion to President Donald Trump. This ideology was second behind religious commitment in predicting whether Americans took up cautious or incautious practices, such as mask-wearing. Thus religion, with political ideology, could move people in either direction.

(The Lifeway Research study can be downloaded here: http://lifewayresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Coronavirus-Pastors-Full-Report-July-2020.pdf; The Pew Research Center Study can be downloaded here: https://www.pewforum.org/2020/08/07/americans-oppose-religious-exemptions-from-coronavirus-related-restrictions; Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/14685906)

![]() The pandemic in Ireland and Northern Ireland saw an increase in online religious participation as well an interest in continuing such alternative forms of spirituality and religion when the crisis is over, according to a study cited in the blog The Emerging Church in Eire and Northern Ireland (August 5, 2020). The blog cites the recent survey by Gladys Ganiel and her colleagues at Queens University (Belfast) of 439 faith leaders from most denominations in the two countries, with a key finding being an “astonishing” rise of engagement with online worship activities during the pandemic. Before the crisis, 44 percent of all churches had no online provision for worship. By the time the survey was conducted in the midst of the pandemic 87

The pandemic in Ireland and Northern Ireland saw an increase in online religious participation as well an interest in continuing such alternative forms of spirituality and religion when the crisis is over, according to a study cited in the blog The Emerging Church in Eire and Northern Ireland (August 5, 2020). The blog cites the recent survey by Gladys Ganiel and her colleagues at Queens University (Belfast) of 439 faith leaders from most denominations in the two countries, with a key finding being an “astonishing” rise of engagement with online worship activities during the pandemic. Before the crisis, 44 percent of all churches had no online provision for worship. By the time the survey was conducted in the midst of the pandemic 87  percent of the churches were engaged in online ministry. Seventy percent of respondents said they would keep some (55 percent) or all (15 percent) of online worship after the pandemic. Like similar research in Great Britain, roughly one-quarter of the public engaged in online worship compared to normal church attendance rate of about 10 percent (in Britain). Faith leaders—in both Great Britain and Ireland and Northern Ireland—noted an increase in online religious practice, especially a deeper desire for prayer and reading the Bible. Those surveyed tended to agree that the current situation was an opportunity for radical change, including rethinking the preoccupation of keeping buildings open and the challenge of finances.

percent of the churches were engaged in online ministry. Seventy percent of respondents said they would keep some (55 percent) or all (15 percent) of online worship after the pandemic. Like similar research in Great Britain, roughly one-quarter of the public engaged in online worship compared to normal church attendance rate of about 10 percent (in Britain). Faith leaders—in both Great Britain and Ireland and Northern Ireland—noted an increase in online religious practice, especially a deeper desire for prayer and reading the Bible. Those surveyed tended to agree that the current situation was an opportunity for radical change, including rethinking the preoccupation of keeping buildings open and the challenge of finances.

(Emerging Church in Eire and Northern Ireland, https://medium.com/@pmphillips/the-emerging-hybrid-church-in-eire-and-northern-ireland-524517ec57a4)

![]() A “global decline of religion” has accelerated since 2007, “with surprising speed,” as lower income nations have joined more secularized high income nations in retreating from faith, writes Ronald F. Inglehart in the journal Foreign Affairs (September/October, 2020). Inglehart has long propagated his theory of how “existential

A “global decline of religion” has accelerated since 2007, “with surprising speed,” as lower income nations have joined more secularized high income nations in retreating from faith, writes Ronald F. Inglehart in the journal Foreign Affairs (September/October, 2020). Inglehart has long propagated his theory of how “existential  security” (freedom from economic distress and longevity) drives down the importance of religion in people’s lives, but he was even has caught off-guard by the sudden growth in secularism around the world. Using the World Values Survey, Inglehart finds that from 2007 to 2019, “overwhelming majority of the countries we studied—43 out of 49—became less religious. The decline in belief was not confined to high-income countries and appeared across most of the world.” This pattern stood in contrast to even as recent a period as the early 2000s when religious beliefs were strengthened in countries of the former Soviet Union as well in such developing nations as Brazil, China, Mexico, and South Africa. The only noticeable exceptions to the secularizing trend are India and most of the Muslim world.

security” (freedom from economic distress and longevity) drives down the importance of religion in people’s lives, but he was even has caught off-guard by the sudden growth in secularism around the world. Using the World Values Survey, Inglehart finds that from 2007 to 2019, “overwhelming majority of the countries we studied—43 out of 49—became less religious. The decline in belief was not confined to high-income countries and appeared across most of the world.” This pattern stood in contrast to even as recent a period as the early 2000s when religious beliefs were strengthened in countries of the former Soviet Union as well in such developing nations as Brazil, China, Mexico, and South Africa. The only noticeable exceptions to the secularizing trend are India and most of the Muslim world.

Inglehart finds the most dramatic change taking place in the U.S. Since 2007, the U.S. showed a drastic drop in the importance Americans give to religion– from a mean rating of the importance of God in their lives at 8.2 on a ten-point scale to a figure of 4.6 by 2017. “By this measure, America now ranks as the 11th least religious country for which we have data,” Inglehart writes. As to why this decline took place so suddenly, he argues that secularization “can reach a tipping point when the dominant opinion shifts and, swayed by the forces of conformism and social desirability, people start to favor the outlook they once opposed—producing exceptionally rapid cultural change. Younger and better educated groups in high-income countries have recently reached that threshold.” Inglehart points out the usual suspects of secularization–“modernization” and technological progress, a reaction against the religious right, and the abuse crisis in the Catholic Church. But he also stresses how the “pro-fertility norms” of most religions as no longer being necessary in many societies, while the secular norms of divorce, abortion, gay rights, and gender equality rapidly gain favor. Even though pandemics, such as COVID-19, can reduce people’s existential security and thus increase the importance of religion, Inglehart doubts the likelihood of such a shift, “because it would run counter to the powerful, long-term, technology-driven trend of growing prosperity and increased life expectancy that is helping push people away from religion.”

(Foreign Affairs, https://www.foreignaffairs.com)

![]() With more than a quarter of the population being unaffiliated and the share of the religious non-affiliated (“nones”) in the UK increasing, this population should be seen beyond a generic category as the long-term influence of their religious upbringing may still be shaping some of their attitudes, writes Yinxuan Huang (University of Manchester) in the Journal of Contemporary Religion (May, 2020). Huang cautions against approaching religious nones in Britain as an undifferentiated category. Many of them had been brought up as Christians and have subsequently renounced their Christian identities, but this does not mean that they have lost their cultural heritage. This raises the question of knowing to which extent this background affects their attitudes and behavior and differentiates them from the other nones. The purpose of the research is to fill a gap through understanding “how internal variations divide the religiously unaffiliated in the UK in terms of political attitudes,” based on the data of the British Social Attitudes BSA) survey of 2016, which was conducted after the referendum on the UK European Union (EU) membership vote. Research findings had suggested that Anglican voters had mainly supported leaving the EU (Leavers), with Catholics, non-Christians and nones more likely to support staying in the EU (Remainers).

With more than a quarter of the population being unaffiliated and the share of the religious non-affiliated (“nones”) in the UK increasing, this population should be seen beyond a generic category as the long-term influence of their religious upbringing may still be shaping some of their attitudes, writes Yinxuan Huang (University of Manchester) in the Journal of Contemporary Religion (May, 2020). Huang cautions against approaching religious nones in Britain as an undifferentiated category. Many of them had been brought up as Christians and have subsequently renounced their Christian identities, but this does not mean that they have lost their cultural heritage. This raises the question of knowing to which extent this background affects their attitudes and behavior and differentiates them from the other nones. The purpose of the research is to fill a gap through understanding “how internal variations divide the religiously unaffiliated in the UK in terms of political attitudes,” based on the data of the British Social Attitudes BSA) survey of 2016, which was conducted after the referendum on the UK European Union (EU) membership vote. Research findings had suggested that Anglican voters had mainly supported leaving the EU (Leavers), with Catholics, non-Christians and nones more likely to support staying in the EU (Remainers).

Huang’s careful analysis of the BSA data shows that both religious upbringing and current religious affiliation were important factors in attitudes towards Brexit. Former Anglicans were more likely to support it than consistent nones by a margin of 10% and were much closer to consistent Anglicans. Interestingly, the voting patterns of former Catholics and consistent Catholics were strikingly similar. Thus, even in a more secular environment, the religious background plays a role in shaping socio-political attitudes. Both an Anglican or a Catholic upbringing leads to the formation of distinct non-religious identities. Even if the beliefs are no longer there, “Christian backgrounds may still have a discernible social function in their close association with nones’ secular perceptions of national, ethnic or cultural identity.” While the nature of a “Christian upbringing” is a matter for discussion, as Huang acknowledges, this research suggests ways into which the cultural influence of religion remains relevant for secular segments of the population.

Huang’s careful analysis of the BSA data shows that both religious upbringing and current religious affiliation were important factors in attitudes towards Brexit. Former Anglicans were more likely to support it than consistent nones by a margin of 10% and were much closer to consistent Anglicans. Interestingly, the voting patterns of former Catholics and consistent Catholics were strikingly similar. Thus, even in a more secular environment, the religious background plays a role in shaping socio-political attitudes. Both an Anglican or a Catholic upbringing leads to the formation of distinct non-religious identities. Even if the beliefs are no longer there, “Christian backgrounds may still have a discernible social function in their close association with nones’ secular perceptions of national, ethnic or cultural identity.” While the nature of a “Christian upbringing” is a matter for discussion, as Huang acknowledges, this research suggests ways into which the cultural influence of religion remains relevant for secular segments of the population.

(Journal of Contemporary Religion, https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/cjcr20/current)