New data on white evangelical voting patterns and views during the 2018 midterm elections show about the same level of support for the presidency of Donald Trump as there was for candidate Trump in the 2016 presidential race. The blog Religion in Public (January 28) analyzed raw numbers recently released from a survey conducted by Data for Progress, the first publicly available dataset from the most recent election cycle. While white evangelicals showed no change in their tendency to vote Republican in 2018, the new data indicated that they actually identified themselves more strongly as Republicans than they did in 2016, particularly those who reported attending church more than once a week. And while other racial and religious groups may have moderated or nuanced their views since the contentious 2016 race, evangelical support for Trump has changed little since then. Among white born-again Protestants attending church more than weekly, 85 percent approved of Trump’s job performance, with the percentage only dropping to 77 percent among those attending once a week. Even for white evangelicals attending church infrequently, over two-thirds still approved of Trump. In comparing the attitudes of white evangelicals with those of other groups regarding such movements and issues as Black Lives Matter and the Affordable Care Act, only the evangelicals showed a level of opposition similar to that they displayed in 2016.

(Religion in Public, https://religioninpublic.blog/2019/01/28/did-evangelicals-become-more-moderate-in-2018/)

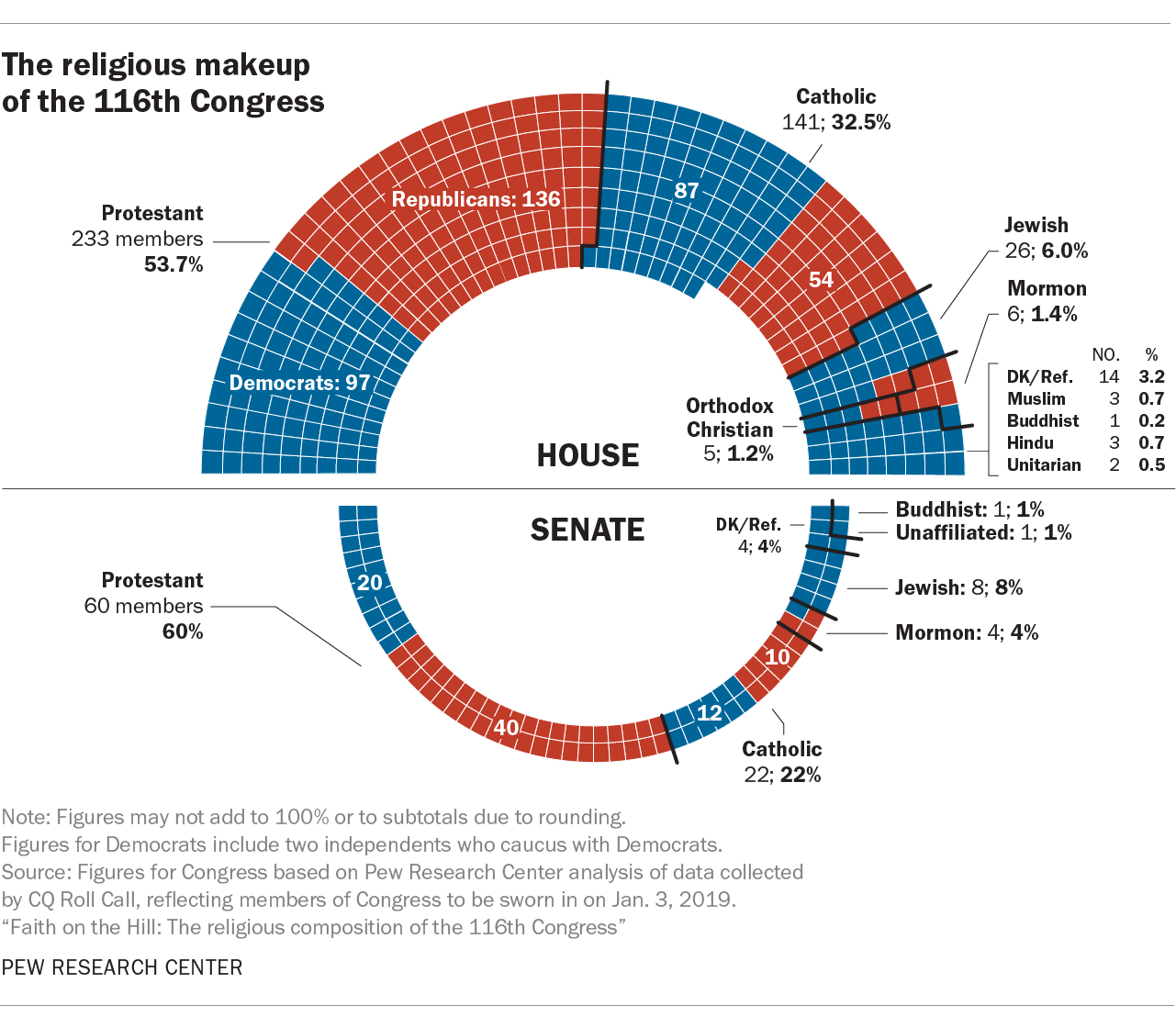

The new Congress is the most religiously diverse in American history, though a new survey from Pew Research finds that the incoming class of legislators is still more Christian than the American population as a whole. The Pew report finds that while the number of self-identified Christians in Congress has dropped, Christians as a whole—and especially Protestants and Catholics—are still overrepresented in proportion to their share in the general population. “Indeed, the religious makeup of the new, 116th Congress is very different from that of the United States population.” The number of Christians in Congress declined slightly compared with the 115th session, dropping from 90.7 percent to 88.2 percent. By contrast, 71 percent of U.S. adults identify as Christians. (Pew’s survey included Catholics, Protestants, Mormons, Orthodox Christians, Christian Scientists and other faith groups in its Christian category.) Most Christians in Congress are Protestant, including 72 Baptists, 42 Methodists and 26 members each for Presbyterians, Lutherans and Anglicans/Episcopalians. Catholics make up 30.5 percent of the members of Congress with 163 members, and Mormons claim 1.9 percent with 10 members. Five members of Congress are Orthodox Christian.

Meanwhile, the influx of non-Christian members into Congress is almost entirely among Democrats or independents who caucus with Democrats. According to Pew, 61 of the 282 Democrats or independents are non-Christian: In addition to 32 Jewish members, all Muslims (three), Hindus (three), Buddhists (two) and Unitarian Universalists (two) in Congress caucus with Democrats. Only one Democrat—Sen. Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona—identifies as religiously unaffiliated, with 18 more declining to specify their religion. By contrast, only two of the 252 Republican members in the 116th Congress—Reps. Lee Zeldin of New York and David Kustoff of Tennessee—identify as something other than Christian (both are Jewish).

(The Pew study on Congress can be downloaded at: http://www.pewforum.org/2019/01/03/faith-on-the-hill-116/)

A new study by sociologist Fr. Paul Sullins finds that the increasing sexual abuse of youth by Catholic priests in the U.S. is correlated with the growing number of homosexuals in the priesthood, according to a report in the magazine Inside the Vatican (December). Because the majority of youth in abuse cases have been boys, the connection between homosexuality and the abuse has been debated since the crisis first came to light in the early 2000s. A study by John Jay College concluded that widespread American abuse was not related to the number of homosexual priests because the reported increase of homosexual men in seminaries during the 1980s did not correspond to the number of boys who were abused. Sullins criticizes the John Jay study because it relied on “subjective clinical estimates and second-hand narrative reports of apparent homosexual activity in seminaries.” He estimated the share of homosexual priests in the U.S. from a survey conducted by the Los Angeles Times in 2002 and compared this against contemporary allegations of abuse, finding that “increase or decrease in the percentage of victims who were male correlated perfectly (.98) with the increase or decrease of homosexual men in the priesthood.” About half of this association was accounted for by the “rise of subcultures or cliques of sexually active priests and faculty in Catholic seminaries.” For each additional concentration of homosexual priests of two times the population proportion of homosexual men (1.8 percent in the U.S. population), incidents of clergy sexual abuse doubled, up to a maximum of 24 incidents per year at a proportion of homosexual priests (14.4 percent) over eight times that of homosexual men in the U.S. population.

(Inside the Vatican, https://insidethevatican.com)

While it may be that nations with high levels of existential insecurity and inequality tend to be more religious, the levels of insecurity experienced among individuals within nations appear to have little effect on their religious beliefs and practices, according to a new study by Franz Hollinger and Johanna Muckenhuber in the journal International Sociology (Vol. 34, No. 1). The thesis that existential insecurity caused by factors such as natural disaster, poverty, and lack of healthcare and insurance drives up religiosity was developed by Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris and has become a leading explanation of why Third World and developing nations are more religious than wealthier Northern and Western countries. Hollinger and Muckenhuber revisit the data from the World Values Survey (2010–2014) and confirm the findings of previous studies that less developed and egalitarian nations rate higher on measures of religiousness than Western countries. But their “striking new finding” is that within these countries “individual experiences of life risks, such as material deprivation and risk of becoming a victim of crime, have no or only a marginal effect on a person’s level of religiousness.” The researchers offer explanations for this apparent discrepancy between macro-level and micro-level effects that include the possibility that existential insecurity is so common in developing countries that only traumatic events have an impact on religiousness. It may also be that individual religiousness is shaped more by the culture and social milieu one lives in rather than by life experiences. “In the majority of cases, people suffering from difficult life conditions are not more religious than other persons living in the same society.”

(International Sociology, https://journals.sagepub.com/home/iss)