Even though it has been considered a conservative religious rallying cry, a Public Religion Research Institute survey finds that 61 percent of Americans oppose allowing businesses to deny services to gays and lesbians. The issue became headline news when the Supreme Court considered taking the case of a Colorado baker who refuses on religious grounds to make cakes for same-sex couples. But the new survey of 40,000 found not a single major U.S. religious group where a majority of members support denying service to same-sex couples. Fifty percent of white evangelical Protestants supported such service denial, but the numbers drop from there: 42 percent of Mormons, 34 percent of Hispanic Protestants, 25 percent of black Protestants, and 25 percent of Jehovah’s Witnesses believe businesses should be allowed to deny services to same-sex couples. USA Today (June 21) reports that the finding is part of a major shift in views of same-sex marriage across the country, where support for same-sex marriage is growing, especially among younger people of all faiths. While 61 percent of white evangelical Protestants still oppose gay marriage, even that group is split by age, with 51 percent of evangelicals under the age of 30 saying they support gay marriage.

While “spiritual but not religious” individuals are usually identified by their eschewing religious affiliation and holding non-institutional beliefs, their strong disavowal of monotheism tends be their defining characteristic, writes Paul McClure of Baylor University in the journal Poetics (62). McClure analyzes the Baylor Religion Survey (Wave 4, 2014) and finds that those who identify as “spiritual but not religious” (SBNR) are more numerous than previous studies have shown, representing about 27 percent of the American population. He found that SBNRs are more likely to hold that all are religions are true but reject monotheistic beliefs, which they view as too exclusive. They tend to understand God as a higher power, interpret the Bible as an ancient book of history and legends, and adhere to an individualistic ethic. McClure links these beliefs to the demographic profile of SBNRs—they are younger, more urban, white, and highly educated. He concludes that SBNR status “accompanies practically a wholesale rejection of traditional religious practices and monotheistic beliefs” and in a sense can be as exclusive as monotheism.

(Poetics, https://www.journals.elsevier.com/poetics/)

Viewing pornography among American young adults is associated with lower rates of congregational attendance, prayer frequency, feelings of closeness to God, and the importance of religion in their lives, according to a study by Samuel Perry and George Hayward in the journal Social Forces (June). The secularizing effect of viewing pornography was found among both men and women and is strongest for teens from 13–17. The researchers, who analyzed the first three waves of the National Study of Youth and Religion, found that while the effects of viewing pornography weaken after age 18, it still negatively affects the two measures of attendance and frequency of prayer. Perry and Hayward theorize that teens living under the moral authority of their parents experience more internalized guilt and cognitive dissonance associated with their pornography use. Although they acknowledge several factors behind what they see as a secularization of youth, pornography use, like involvement in drinking, drug use, and premarital sex, weakens adolescent attachment to religion.

(Social Forces, https://academic.oup.com/sf/issue)

While Muslims appreciate the freedom that they enjoy in the United Kingdom, they feel that a strict practice of Islam does not always fit with the lifestyle of the local society and consider the lack of a unified representation of Muslims as a weakness in comparison to established religious bodies. That was the main finding of Turkish migration studies scholar Onur Unutulmaz (Ankara University) in a paper presented at a conference on the religious and ethnic future of Europe, organized by the Donner Institute and the Migration Institute of Finland in Turku (Finland), that RW attended. According to the 2011 census, the UK has a Muslim population of 2.7 million (up from 1.55 million ten years earlier), making up 5 percent of the total population. The researcher finds that 68 percent of UK Muslims are of Asian background, and 47 percent are UK-born. Thirty-three percent of Muslims are 15 years old or younger (compared with 19 percent of the general population). Freedom of speech, rule of law, social and welfare rights, and ability to practice their religion are some of the advantages Muslims in the UK enjoy.

But they are concerned about the kind of image Muslims have in the country, with wrong people assumed to represent Muslims in the media and an obvious lack of unity. Respondents hope to have a common governing structure, such as a Grand Mufti, although they are aware that the divisions within the community would make it difficult to select one and might end up only in creating more divisions. The prominence of first-generation migrants in religious institutions is perceived as part of the problem, and the need for building up more competence is emphasized. Unutulmaz’s presentation also offered the opportunity to introduce a new research project launched under the auspices of the Statistical Economic and Social Research and Training Centre for Islamic Countries (SESRIC), a subsidiary organ of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). Mostly confined to economic topics until now, SESRIC enters the field of social sciences with its Global Muslim Diaspora (GMD) Project, now in its initial stage with fieldwork starting in the UK and continuing in France and Germany. In addition to country reports, the long-term goal is the production of an interactive GMD atlas.

The majority of migrants coming to Norway are keeping their religion, with the exception of people of Iranian descent, of whom only one out of ten states that religion is important. Anette Walstad Enes (of Statistics Norway) reported these findings of newly released research at the conference on the religious and ethnic future of Europe that took place in Turku, Finland, on June 12–13 attended by RW. The research was conducted on a sample of 4,200 immigrants from 12 countries (350 per country) as well 1,000 people born in Norway to immigrant parents. The response rate was 54 percent. The countries of origin were Vietnam, Poland, Sri Lanka, Eritrea, Iran, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Kosovo, Iraq, Turkey, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Somalia.

The level of religious affiliation is 80 percent and above for all groups except for people from Iran (less than 50 percent) and from Bosnia-Herzegovina (below 70 percent). In a strong majority of cases, people report still belonging to the same religion as the one in which they were raised—except for people of Iranian background, of whom only 52 percent persevere in the religion of their childhood. The percentage is 83 percent for people from Poland, 84 percent for people from Bosnia-Herzegovina, 88 percent for people from Vietnam, 89 percent for people from Iraq and Kosovo, while all the other national origins are above 90 percent. Seventy percent or more of the respondents (depending on the country of origin) find it very easy or easy to practice their religion in Norway, while only a small percentage for each religion sees it as difficult or very difficult.

(The website of Statistic Norway makes this material on migrants and religion as well as on various other relevant topics available in English at: https://www.ssb.no/en/innvandring-og-innvandrere/nokkeltall/immigration-and-immigrants)

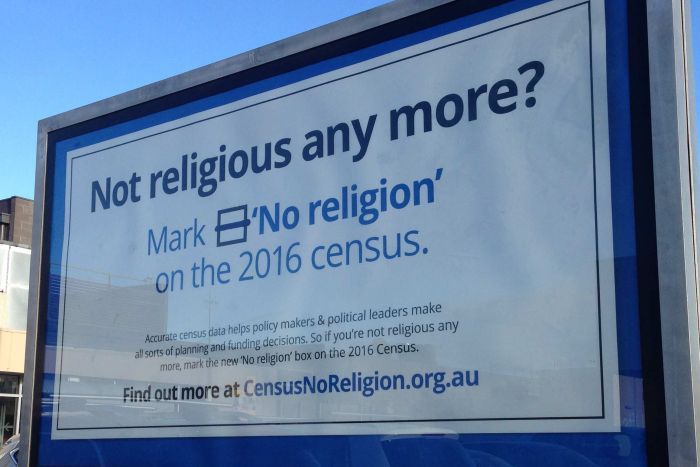

More Australians do not identify with a religion than with any single religion, a first for a country that had been predominantly Catholic, according to new data from the nation’s census. Nearly 30 percent reported “no religion,” compared to 23 percent Catholic and 13 percent Anglican. Despite the rise in the unaffiliated, who represented 0.8 percent of Australia’s population in 1966, the growth of pluralism was also evident. Fifty years ago, census data showed that more than 88 percent of the country was Christian. Christians now comprise just over 52 percent. Since the last census in 2011, the country’s Muslim and Hindu populations each added more than 100,000 people, but they still represent only 2.6 percent and 1.9 percent of the population, respectively. There are still more Buddhists than Hindus. The survey had a 95 percent response rate, reports CNN (June 27).

Despite shrinking church attendance in Sweden, there has been a revival of religious interest that suggests younger generations of Swedes may replace older more secular ones, according to a study in the Review of Religious Research (online in June). Political scientist Magnus Hagevi analyzes longitudinal data on religious affiliation and pluralism, comparing it to data on religious interest among different generations in Sweden. The research finds that while the pre-war generation tended to value salvation the most, such interest dropped considerably for baby boomers. But starting with Generation X and then intensifying with millennials, the valuing of salvation exceeds that of the baby boomers. In contrast to traditional ideas of an ongoing secularization, Hagevi argues that there has a been a de-regulation of the religious market that Swedish young people are only now beginning to feel due to a time lag.

He adds that it was only when compulsory religious practices—such as formal teaching on religion in the schools—lost ground in 1970s Sweden that the religious market began to develop. Baby boomers who were forced to participate in such rituals tended to show high rates of religious disinterest. But generations X and Y (the millennials) were raised in this deregulated religious market and therefore may not have developed negative views of religion. The researchers controlled for immigrants, who have higher religious interests, and found that the higher religious interests of the younger generations, especially millennials, remained.

(Review of Religious Research, https://link.springer.com/journal/13644)

Survey researchers have often ignored Bangladesh, but a new study suggests that the troubled country shows a growing tendency to support religious conflict and violence. The study, published in the journal Politics and Religion (online in June) and conducted by C. Christine Fair, Ali Hamza, and Rebecca Heller of Georgetown University, is based on the recent Pew data on a country that has been underrepresented by large-scale surveys and overlooked by the security studies community. The researchers find that fairly strong support for extremism accompanies two decades of conflict in Bangladesh between those supporting secularism and Islamic militancy, punctuated by 100 terrorist attacks. “Variables that strongly predict support for suicide bombings…have significant support,” they add. There is also popular support for Islamic leaders providing dispute resolution, with 70 percent of respondents embracing it: “While education seems to mitigate support for violence, higher perceived economic standing exacerbates it.”

(Politics and Religion, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-religion)