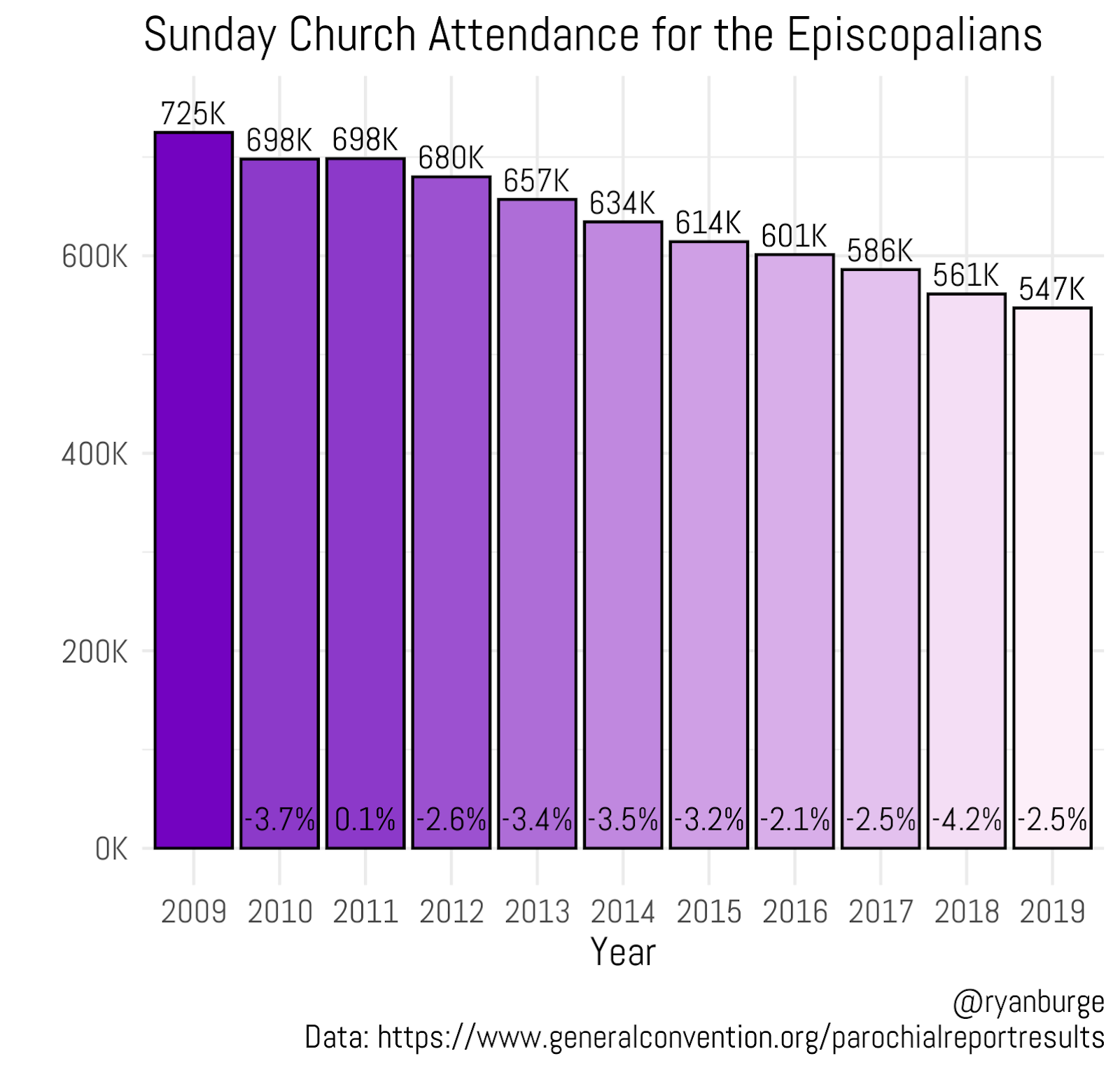

This means that the church has dropped by one-third between 2000 and 2020. Accompanying this drop in attendance, there was a noticeable reduction in offerings and pledges between 2019 and 2020, indicating that donations are not keeping pace with inflation. Other indicators, including marriages, baptisms, burials, and confirmations, are also in serious free fall. While it could be argued that these declines were natural given the church shutdowns in 2020, Burge finds that right before the pandemic, in 2019, there were only 17,713 baptisms—a nearly 50 percent decline from 2013, when Episcopal dioceses had conducted 33,000 baptisms. Before the pandemic, the church had already lost 30 percent of confirmations. More ominously, in 2019, there were more burials than baptisms and weddings. Burge cautions that the figures to be released for 2022 may well rebound to 2019 levels, and it will be important to find out which activities will come back the fastest or slowest.

This means that the church has dropped by one-third between 2000 and 2020. Accompanying this drop in attendance, there was a noticeable reduction in offerings and pledges between 2019 and 2020, indicating that donations are not keeping pace with inflation. Other indicators, including marriages, baptisms, burials, and confirmations, are also in serious free fall. While it could be argued that these declines were natural given the church shutdowns in 2020, Burge finds that right before the pandemic, in 2019, there were only 17,713 baptisms—a nearly 50 percent decline from 2013, when Episcopal dioceses had conducted 33,000 baptisms. Before the pandemic, the church had already lost 30 percent of confirmations. More ominously, in 2019, there were more burials than baptisms and weddings. Burge cautions that the figures to be released for 2022 may well rebound to 2019 levels, and it will be important to find out which activities will come back the fastest or slowest.

, it is not clear that this has meant rapidly growing non-belief. The researchers reviewed five recent population surveys: the 2018 General Social Survey (GSS), 2017 Values and Beliefs of the American Public survey, 2012 Portrait of American Life Study, 2020 World Values Survey, and the 2018 Chapman University Survey of American Fears. They highlight the GSS findings on atheists and agnostics, where significant percentages were found to have attended religious services at least once a month (6.42 percent of atheists and 27.4 percent of agnostics), prayed at least once a week (12.84 percent of atheists and 58.07 percent of agnostics), and believed in life after death (19.23 percent of atheists and 75 percent of agnostics).The other surveys confirmed these findings to some degree, also showing that a segment of atheists and agnostics meditated, reported that religion and spirituality were important, and believed in miracles. If atheists and agnostics report some religious and spiritual beliefs and activities, then the broad group of “nones” includes even more diversity of beliefs. The researchers argue that media and intellectual elites have fastened on to the idea of religious decline because they tend to identify with mainline Protestantism and apply the long-term declines in this segment of American religion to religion in general. Levin, Bradshaw, Johnson, and Stark conclude that while it may indeed be the case that religiosity is declining, the jury is still out on whether the rise of the nones is a conclusive sign of such a decline.(Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, https://www.religjournal.com/)

, it is not clear that this has meant rapidly growing non-belief. The researchers reviewed five recent population surveys: the 2018 General Social Survey (GSS), 2017 Values and Beliefs of the American Public survey, 2012 Portrait of American Life Study, 2020 World Values Survey, and the 2018 Chapman University Survey of American Fears. They highlight the GSS findings on atheists and agnostics, where significant percentages were found to have attended religious services at least once a month (6.42 percent of atheists and 27.4 percent of agnostics), prayed at least once a week (12.84 percent of atheists and 58.07 percent of agnostics), and believed in life after death (19.23 percent of atheists and 75 percent of agnostics).The other surveys confirmed these findings to some degree, also showing that a segment of atheists and agnostics meditated, reported that religion and spirituality were important, and believed in miracles. If atheists and agnostics report some religious and spiritual beliefs and activities, then the broad group of “nones” includes even more diversity of beliefs. The researchers argue that media and intellectual elites have fastened on to the idea of religious decline because they tend to identify with mainline Protestantism and apply the long-term declines in this segment of American religion to religion in general. Levin, Bradshaw, Johnson, and Stark conclude that while it may indeed be the case that religiosity is declining, the jury is still out on whether the rise of the nones is a conclusive sign of such a decline.(Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion, https://www.religjournal.com/)

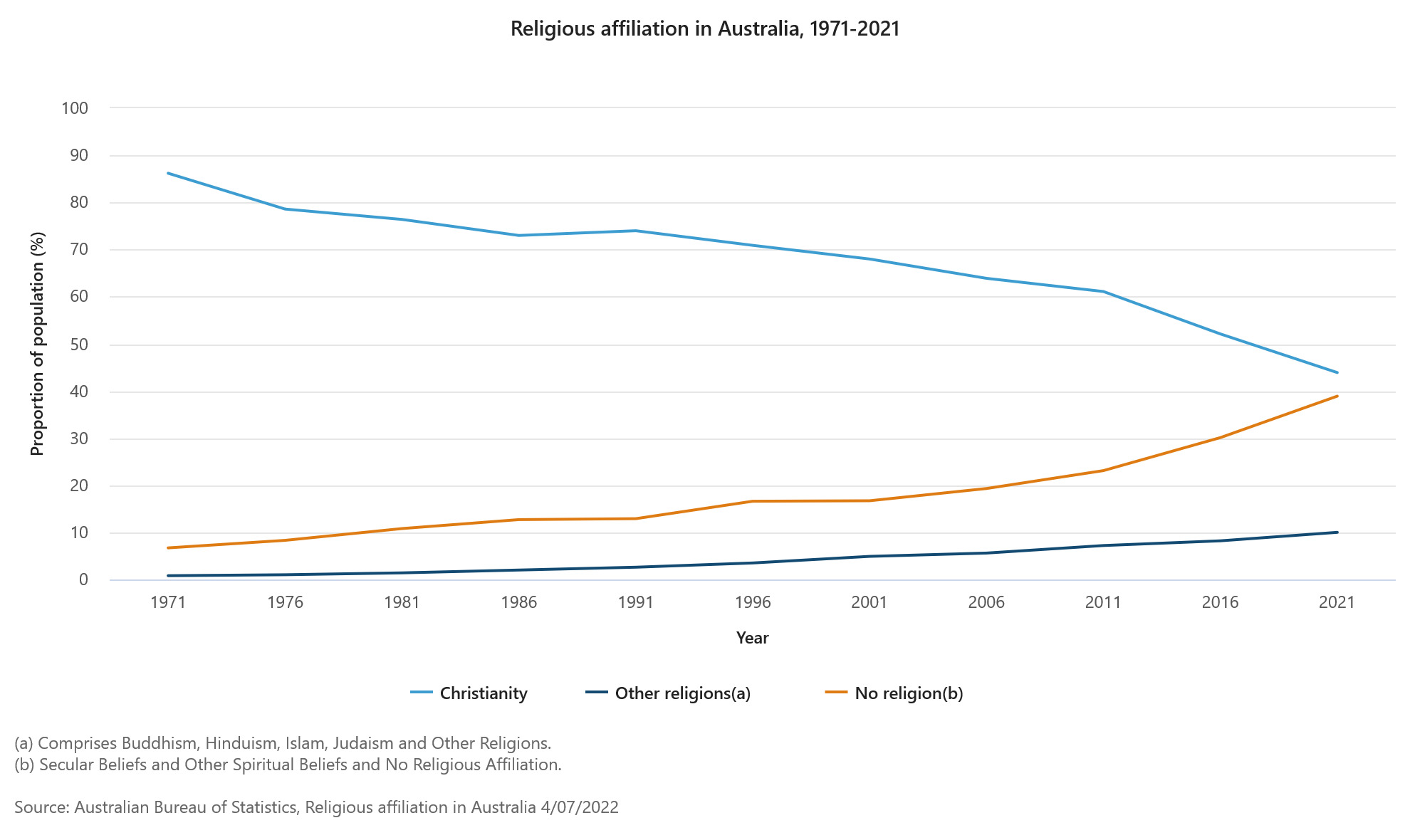

It is also thanks to immigration from Southeast Asia and South America that the decrease of Catholicism has been slowed (although the church still lost 215,000 people). On the other hand (as indicated in the June issue of RW), Anglicanism is declining at a fast pace. “From 2016 to 2021, Anglican affiliation had the largest drop in number of all religious denominations—from 3.1 million to 2.5 million people. This was a decrease of nearly one in five Anglicans, from 13.3 percent to 9.8 percent of the population.” The Uniting Church, Presbyterian and Reformed, and Lutheran denominations have also been declining, as well as Pentecostals (although more modestly, with a loss of 4,700 people). As mentioned, Eastern Christian churches have all been increasing, with the Greek Orthodox being the largest of them and accounting for 1.5 percent of Australians in 2021. The decrease in Christian affiliation has been most marked among young adults (18–25 years). The bureau notes that most of the responses in the broad category, “Secular Beliefs and Other Spiritual Beliefs and No Religious Affiliation,” were in the sub-category “No religion,” with about 9.77 million responses. Only 37,800 people chose atheism, 31,680 selected agnosticism, and 2,190 opted for humanism, suggesting that the prospects for a growth of “organized non-religion” look rather low.(Religious affiliation in Australia: Exploration of the changes in reported religion in the 2021 Census, https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/religious-affiliation-australia#understanding-religious-affiliation)

It is also thanks to immigration from Southeast Asia and South America that the decrease of Catholicism has been slowed (although the church still lost 215,000 people). On the other hand (as indicated in the June issue of RW), Anglicanism is declining at a fast pace. “From 2016 to 2021, Anglican affiliation had the largest drop in number of all religious denominations—from 3.1 million to 2.5 million people. This was a decrease of nearly one in five Anglicans, from 13.3 percent to 9.8 percent of the population.” The Uniting Church, Presbyterian and Reformed, and Lutheran denominations have also been declining, as well as Pentecostals (although more modestly, with a loss of 4,700 people). As mentioned, Eastern Christian churches have all been increasing, with the Greek Orthodox being the largest of them and accounting for 1.5 percent of Australians in 2021. The decrease in Christian affiliation has been most marked among young adults (18–25 years). The bureau notes that most of the responses in the broad category, “Secular Beliefs and Other Spiritual Beliefs and No Religious Affiliation,” were in the sub-category “No religion,” with about 9.77 million responses. Only 37,800 people chose atheism, 31,680 selected agnosticism, and 2,190 opted for humanism, suggesting that the prospects for a growth of “organized non-religion” look rather low.(Religious affiliation in Australia: Exploration of the changes in reported religion in the 2021 Census, https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/religious-affiliation-australia#understanding-religious-affiliation)

Source: Ukrinform.

(Bitter Winter, https://bitterwinter.org/200-religious-buildings-destroyed-or-damaged-by-the-russians-in-ukraine/)