While young people are commonly viewed as less religious than older Americans, a new study by Springtide Research Institute finds that 78 percent of people between the ages of 13 and 25 consider themselves at least slightly spiritual, including 60 percent of unaffiliated young people (atheists, agnostics and nones). The institute’s new study, State of Religion and Young People 2020, also finds 71 percent saying they are at least slightly religious, including 38 percent of the unaffiliated. The study finds a significant degree of eclecticism and non- institutionalism among respondents. Rather than having religious ceremonies led by ordained ministers at houses of worship, Generation Z is developing more personalized marriage rituals that mix secular or cultural sources. The same applies to everyday life, with respondents mixing and matching religious and spiritual support to manage life’s challenges. The study did find that over a third of respondents (35 percent) said their faith had become stronger, while only 11 percent said their faith became weaker (and half said their faith remained stable).

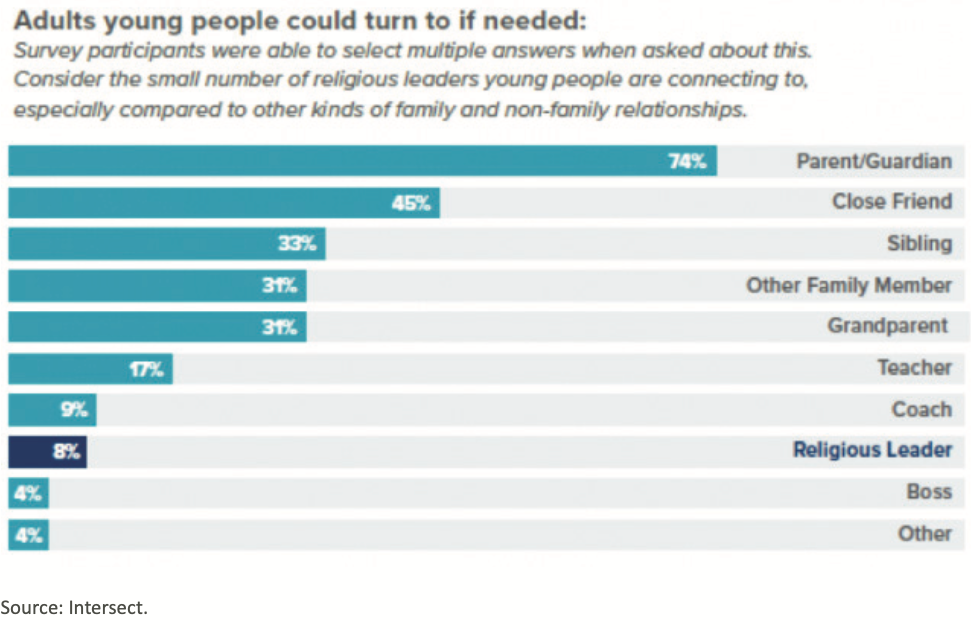

The study confirmed the low institutional trust of Generation Z. When asked to rate their trust of organized religion on a 10-point scale, a majority of young people (63 percent) answered five or below, including a surprising 52 percent of the religiously affiliated. While there was more trust in relationships with people in religious institutions, few religious leaders actually seem to be building such relationships. Eight percent of respondents said there was a religious leader they could turn to, and just 10 percent reported that a religious leader had checked on them during the first year of the pandemic.

(The study can be downloaded from: https://www.springtideresearch.org/research/the-state-of- religion-young-people)

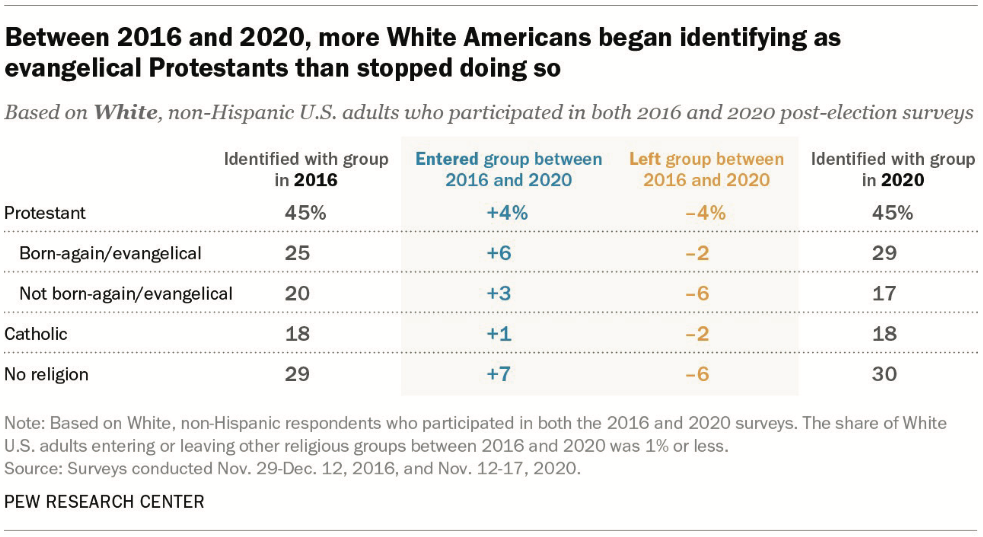

Contrary to media reports, a Pew Research Center analysis finds there was no large-scale departure from evangelicalism among whites during the Trump years. The analysis, appearing on Pew’s blog Fact Tank (September 5), found that white Americans were actually more likely to identify as evangelicals four years after Trump was elected, at least among those who viewed the president favorably. The surveys did not even show that evangelicals who opposed Trump were significantly more likely than Trump supporters to drop the evangelical label. Pew also found that Trump’s electoral performance among white evangelicals was stronger in 2020 than in 2016, which was partly due to increased support among white voters who already described themselves as evangelicals during this period.

There was a small segment of evangelicals who did stop identifying with the label during the Trump years. Among white respondents who took part in both surveys, two percent identified as born-again/evangelical Protestants in 2016 but no longer did so by 2020. But this was offset by the six percent of whites who began calling themselves born-again/evangelical Protestants during the same period. Interestingly, there were more defections by 2020 among white Protestants who did not identify as born-again or evangelical in 2016.

(Fact Tank, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/09/15/more-white-americans-adopted- than-shed-evangelical-label-during-trump-presidency-especially-his-supporters/)

A recent survey of Muslims in Australia finds considerable diversity, especially on controversial questions such as sharia (Islamic law). The study, conducted by Halim Rane and Adis Duderija and published in the journal Contemporary Islam (online in September), is based on a survey of 1,034 Australian Muslims carried out in 2019 and 2020. The researchers asked respondents whether they agreed with a series of statements corresponding to different typologies of approaches to Islam that have been proposed by previous scholars, including Sufi, strict legalist, militant, political Islamist, moderate, traditionalist, progressive, and secular typologies. They found that most Muslim Australians hold liberal positions, believing Islam is aligned with human rights and democracy and seeing their faith as personal and spiritual rather than political (secular and Sufi typologies), while also following traditional understandings of Islam. Smaller minorities agreed with statements corresponding to the strict legalist (applying sharia to society), political Islamist, and militant (using force in applying sharia) categories. Rane and Duderija conclude that their findings are noteworthy since they debunk claims made by “media and political discourses that frame [Islam] and its adherents as a security threat.”

(Contemporary Islam, https://www.springer.com/journal/11562)