![]()

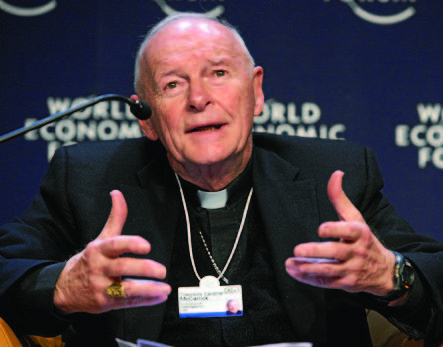

Theodore Cardinal McCarrick (source: World Economic Forum, 2008 – Creative Commons).

The case of Cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s sexual abuse, and its cover-up by his fellow bishops and clerics reflects less a singular instance of clerical misbehavior than a vulnerable episcopal system in which “bad actors find it more or less easy to operate, survive, and thrive.” So write sociologist Stephen Bullivant and psychologist Giovanni Radhitio Putra Sadewo in the Catholic Herald (April 18), based on their study of episcopal networks surrounding McCarrick. The former archbishop of Washington, DC, McCarrick is the most prominent church leader to be charged with sex abuse in recent years, even as he enjoyed widespread acceptance and respect from the Vatican (where he served in various positions) and the American Catholic leadership. Bullivant and Sadewo describe overlapping webs of associations among the episcopal subordinates in the “serving networks” of McCarrick and his mentors, New York’s Cardinal Francis Spellman (who has been accused of abuse himself) and Cardinal Terence Cooke. This doesn’t mean that all of the bishops in these networks were complicit or even knowledgeable of McCarrick’s (or Spellman’s) actions, although several were.

Bullivant and Sadewo write that these serving networks show the “relative ease with which a single, influential kingmaker—a McCarrick, that is—can ‘stack the episcopate.’ Many of these will, inevitably, be his own protégés and favorites, who are in turn more likely to help out their fellows, and to have a collective stake in protecting their patron, whether from loyalty or naked self-interest.” The authors point to the recent investigations into Michael Bransfield, the exbishop in West Virginia who was expelled for allegations of sexual abuse, as supportive of the patterns they outline. He was also a protégé of McCarrick, who performed his consecration as bishop. Bullivant and Sadewo conclude by warning readers to “make no mistake, McCarrick wasn’t the first, and we strongly doubt Bransfield will be the last.”

(Catholic Herald, https://catholicherald.co.uk/how-mccaricks-happen/)

![]()

In the largest study conducted to date on vaccine acceptance and religious groups, a Public Religion Research Institute survey finds that faith-based influences are present in varying degrees among vaccine-hesitant communities. The survey found more than one in four (26 percent) of those Americans who are hesitant to get a Covid-19 vaccine, and even eight percent of those who are resistant to getting the vaccine, reporting that a “faith-based approach” supporting vaccinations might get them to change their position. These approaches included a religious leader encouraging acceptance of vaccines, congregational forums on the issue, a congregation serving as a vaccine site, and a fellow believer receiving the vaccine. Such approaches might be especially relevant to Protestants, who have higher rates of vaccine hesitancy and refusal. Hispanic Protestants are particularly likely to be vaccine-hesitant and resistant (42 percent and 15 percent, respectively), but nearly three in ten white evangelical Protestants (28 percent) are vaccine-hesitant, and an additional one in four (26 percent) are resistant to getting a vaccine shot. Black Protestants are divided along similar lines (with 32 percent hesitant and 19 percent resistant). But church attendance plays different roles among black and white evangelical Protestants. Among blacks, attending religious services is positively correlated with vaccine acceptance, while only 43 percent of white evangelical Protestants who attend religious services frequently are vaccine acceptors compared to 48 percent who attend less frequently.

Religion Unplugged (April 22) reports that the organization Data for Progress has been polling on vaccine acceptance by faith tradition since January, asking respondents if they had received at least one dose of the Covid-19 vaccine. While the share of the American public. receiving at least one dose just about doubled every month as the vaccines were rolled out and became more widely available, disparities emerge when the sample is. broken down into the three largest religious groups, white evangelicals, white Catholics, and the religiously unaffiliated. Ryan Burge notes that “white Christians were significantly more likely to get the vaccine than the general public between January and April. In the latest wave of the survey, nearly 60 percent of white Catholics had been vaccinated and just about half of white evangelicals said the same. It was the religious ‘nones’ that were lagging far behind, with only 31 percent indicating that they had received one dose.” This is in contrast to the 44 percent of the general public that reported getting at least one dose by April. Of course, the nones are a diverse group, made up of atheists, agnostics, and those indicating that their religious affiliation is “nothing in particular,” and the latter’s vaccination rate, in particular, has lagged behind the general public’s, with only 28 percent having received at least one dose by April, compared to 40 percent of atheists and agnostics. Among those Americans who have not been vaccinated yet, the overall share saying they are unlikely to ever get the vaccine has increased, up to 53 percent by April, and when it comes to religious tradition, there seems to be little significant variation in this hesitancy. “Taken together, there’s not compelling evidence here that any religious factor is either driving up or tamping down willingness to get the vaccine,” Burge writes.

(The Public Religion Research Institute’s survey can be downloaded at: https://www.prri.org/research/prri-ifyc-covid-vaccine-religion-report; Religion Unplugged, https://religionunplugged.com/news/2021/4/22/data-shows-evangelicals-and-catholics-more-likely-toget-vaccine-than-nones-and-general-public)

![]() A new study published in the journal Social Forces, based on data from over 20,000 United Methodist congregations between 1990 and 2010, finds that racial diversity inside a church is associated with higher average attendance, especially when the church is located in a white neighborhood.

A new study published in the journal Social Forces, based on data from over 20,000 United Methodist congregations between 1990 and 2010, finds that racial diversity inside a church is associated with higher average attendance, especially when the church is located in a white neighborhood.

Source: Harbor Genesis Christian College.

The study finds that while the United Methodist Church is predominantly white, its racially diverse congregations show more vitality than its white churches, even though the denomination as a whole is experiencing declining attendance. “If the Methodist pattern is true of other denominations, pursuing racial diversity is a strategy for growth,” said Kevin Dougherty, associate professor of sociology at Baylor University and the lead author of the study. Since the 1970s, church growth specialists have held that successful churches are racially and culturally homogeneous, and even more recent studies have found that attracting and keeping a mix of different races within a congregation can be challenging.

![]()

The changing relationship between religion and politics may be a significant driver in the growth of African Americans who are abandoning organized religion, writes sociologist Musa al-Gharbi on Interfaith America (April 16), the website of the Interfaith Youth Core. Since recent studies have shown that unaffiliated African Americans continue to hold religious beliefs and even engage in religious practices much more than their white “none” counterparts, why are they leaving religious institutions in the first place? Al-Gharbi writes that “non-black Americans tend to be much more insistent in a separation between religion and politics. When preachers push political views that are inconsistent with their partisan affiliation, they tend to abandon the faith, and often seem to elevate politics in the aftermath as a replacement for religion. For African Americans, the opposite dynamic seems to be at play—many may be leaving because contemporary black churches are not political enough.” While most blacks are not strongly on board with progressive politics, “they do want their religious leaders and institutions to be out front in helping to address the social problems they have to reckon with in their day to day lives. Yet, there has been a shift within black churches in recent decades—a pivot away from the social gospel and towards the focus on individual faith and prosperity characteristic of many sectors of white Christianity,” al-Gharbi writes.

Source: Black Perspectives.

As a result of this shift, blacks appear to be increasingly alienated from religion. Such an abdication of leadership on the part of faith leaders “seemed to be particularly acute during the contemporary campaigns for racial justice and the Covid-19 pandemic, leading many to explicitly question the continued relevance of black religious institutions for the times we are living in.” But, interestingly, when blacks leave the church, they become significantly more likely to vote Republican, while whites show an opposite pattern, becoming much more likely to vote Democrat after drifting from religion. “The black church and the Democratic Party have long been strange bedfellows – and it looks like growing shares of African Americans are losing faith in both institutions, viewing neither as sufficiently responsive to their values, priorities and interests.” Religious Americans of most faith traditions have been seen moving towards the GOP over the last four years. But the six-percentage-point drop in religious affiliation among African Americans may also help explain the significant gains Republicans made among voters of color in 2020—even if the GOP seems to have taken up a “strategy of attempting to suppress or neutralize our votes,” al-Gharbi concludes.

(Interfaith America, https://ifyc.org/article/black-americans-crave-deeper-integration-religionand-politics)

![]()

Source: Atheist Republic.

The share of atheists in Russia has doubled over the past four years, reports Victoria Ryabikova in Russia Beyond (April 15). According to an opinion poll by the All-Russia Center for the Study of Public Opinion (VTsIOM), the proportion of atheists has grown from 7 percent in 2017 to 14 percent in 2021. However, 66 percent of Russians still consider themselves to be Orthodox, with the percentage being higher among those over age 35. Seventeen percent report attending religious services during the period of Great Lent before Easter. And while a number of young people turn to atheism, there are also some who turn away from atheism to faith, Ryabikova remarks. Nevertheless, the apparent relatively rapid increase in the percentage of atheists deserves attention. Many among those who are older admit that the legacy of the Soviet period with its atheist propaganda has contributed to shaping their beliefs. For younger people, on the other hand, the embrace of atheism is a matter of choice, especially when they have been raised in religious families and then given up faith.

Perceived contradictions between science and religion seem to come into play when young people start asking themselves questions. Other people are reported to resent the public role and influence of the Orthodox Church. An expert on religious affairs, Vyacheslav Terekhov, agrees that a negative image of the church, stemming from media portrayals and state attempts to use it as an ideological tool, is a factor for some people who turn to atheism, but remarks that the growing number of atheists has not reached a critical level and “is not an indicator of the collapse of the church as an institution.” One should wait to see if the trend identified by the recent poll is confirmed. Meanwhile, some priests agree that the new popularity of atheism among segments of the younger population raises a missionary challenge for the church, and stress the need to develop better ways of convincingly presenting the message of Orthodoxy beyond broadcasting religious services (360° [in Russian], March 23).

(Russia Beyond, https://www.rbth.com/lifestyle/333670-more-and-more-russians-are-becomingatheists)